By Jake Kivanc

Don’t move. Seriously, just stay down,” my friend whispered as we lay pancaked to the hard floor of a dusty rooftop. A small concrete wall, unpainted and serrated with exposed rebar, cast a shadow just large enough to conceal our bodies from the security guard peering out into the tangled construction site with his flashlight. After sneaking into an unauthorized area of an unfinished building overlooking Spadina Avenue, we were about to be caught. Although we had come up here for a thrill and some gnarly photos, we were probably going to leave in handcuffs. At least the pictures would net us some new followers.

Instagram, for better or worse, has fundamentally changed the nature of photography. Not just in the way it’s received by the public, but in the way it’s produced and sought out. Gone are the days of dark rooms and Polaroids — two concepts now only associated with enthusiasts and hipsters — digital photography now rules the game and is more accessible than ever. Whether you’re shooting with a cell phone or a bulky DSLR, beautiful imagery can be captured, edited and put online for the world to see with relative ease and haste.

But with improved accessibility, there also comes a great cost: if you want to stand out as a photographer in the world of social media, you have to pay the price of pushing the boundary, sometimes to the point of real and tangible danger.

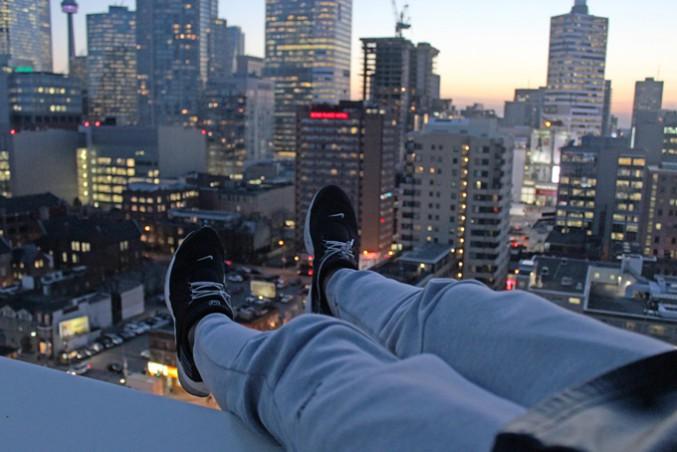

This trend is no more apparent than across the streets of Toronto. Shooters roam the city in search of not just the best imagery, but the most daring locations. Photographers looking to make a splash on Instagram often crouch in the middle of bustling streets as cars whiz by, while explorers and those with a thirst for adrenaline climb and scale buildings to access rooftops and take “dangler shots,” where people droop their legs over the edge of a building in order to photograph their shoes hanging over the ground below.

It’s a trend that’s dangerous, exhilarating and has produced some of the prettiest eye candy on the web, but not everybody agrees in it being the end-all of the photography game.

“It’s amazing how many ’grammers want to get to a certain spot so badly and then when they get there they just replicate the exact same shot that someone big like Jayscale has taken,” said Brad Golding, a Ryerson RTA student and Toronto photographer. “It makes no sense to me.”

Golding, who goes by the handle @goldshoots on Instagram, has a photo feed mixed with lifestyle and cityscape shots. Some of his pictures, which he says are taken “on the go” in his day-to-day life, are something more typically associated with amauteur photography. Creamy shots of friends walking around a city in the middle of fall, a bird’s-eye view of a latté and a book, a street capture of a businessman rushing to work. Golding tells me he used to take shots for the followers, but now he does it just for himself.

“When I take photos I think a lot about the story behind the moment and sometimes that story is only relevant to me, but that’s not a bad thing at all,” he said. “Of course I want a lot of people to see and enjoy my work, but I take photos just as much for me as I do for others.”

The shift toward edgier and danger-filled photography in Toronto can be traced back to 2010. Just before Instagram had its humble beginnings as a simple app to capture and share photos from a smartphone, the real photography arena existed on sites like Flickr and 500px. One of the first notable examples of dangler photography was created by photojournalist Tom Ryaboi, who took a shot of his friend Jen Tse’s legs suspended off the edge of a Toronto skyscraper. The picture of Tse’s black and white converse looming over Yonge and Wellington streets blew up — making international news in just a week after being featured as an Editor’s Pick on Reddit.

“It’s amazing how many ’grammers want to get to a certain spot so badly and then when they get there they just replicate the exact same shot”

“Everything happened really quickly from there, all kinds of doors swung open. I was offered the photo editor position of Toronto’s leading blog. I began to licence loads of my images, and I was selling tons of prints, all thanks to one photo,” Ryaboi, former BlogTO editor, wrote on a blog four years ago. “Even now, a year later, I still get three to five requests for this photo every week.”

Since then, rooftopping culture has exploded. Some of the most popular Instagram accounts and photography collectives consistently feature wide shots of Toronto’s skyline or stomach-churning photos of Air Jordans dangling above city streets, all of which have been taken from the top of grandiose buildings and towers in the downtown core.

Some photographers go as far as scaling cranes and hanging onto railings with one hand while taking pictures with the other. The further you push it, the more likes you’re generally going to get.

But according to the Toronto Police, rooftopping isn’t just dangerous, it’s illegal, and some photographers already have had to pay a serious price for their adventures. Earlier this year, then-Ryerson journalism student Eric Mark Do was arrested by police with a few friends, one of whom was Ryaboi, after they were caught on top of a building near the west end of Wellington Street Do was charged with three charges related to breaking and entering. Although charges against the three photographers were dropped in September, Do’s photography gear was seized until May and the cards holding the photos were held until after the charges were released. Now, photos from the same rooftop can be found as some of the most recent posts on his Instagram.

Toronto Police Const. Victor Kwong said that while the degree of repercussions for rooftoppers are determined by the courts, there is a great amount of leeway in both an officer’s and a judge’s ability to interpret the situation, noting that “breaking and entering” doesn’t necessarily have to involve breaking any locks.

“‘Breaking’ does not mean damage, rather figuratively of a threshold. For example, just because you forgot to lock your door doesn’t mean it’s okay for anyone to walk into your home,” Kwong said. “Officers have discretion on whether or not to lay a charge.”

“It’s one thing to climb, but being able to bring the proof back with photos is different.”

Getting up to rooftops can be a difficult and daunting task. Oftentimes, photographers have to evade building security, as well as the various apparatuses that may be monitoring breaches in doors and hatches that may allow access to the roof. Due to the rise in popularity of rooftopping and the people being caught doing it, however, building security around the city has improved drastically.

In my experience talking to frequent rooftoppers, almost any building worth scaling requires some form of lock-picking tools. This can range from something as simple as a screwdriver or knife to wedge open a door, to full-fledged bolt cutters that are used to snip off padlocks keeping the photographer from the top of the building.

There are other elements to take into account, such as cameras, motion sensors and electronic strips that can alert security to someone trying to access unauthorized areas. It’s become so difficult and legally risky that virtually no photographers are willing to speak on the record about their experiences rooftopping, nor are there guides or how-tos online for first-timers looking to give it a swing.

With such secrecy, those with the knowhow are revered in the community. Bigtime Instagrammers in Toronto such as Jayscale and Brxson have racked up tens of thousands of followers — their feeds a conspicuous mix of death-defying shots from the top of Toronto’s tallest buildings and simple photography down on the street level. Regardless of location, the imagery is always popping with crisp detail and clarity. It’s a culture that is defined by hashtags like #way2ill, #shoot2kill and #hypebeast. As old hashtags die, new ones are born, all of which have their own respective niche to serve before the community hops onto the next trend.

Things weren’t always this way. Peter Bregg, a Ryerson professor who teaches classes on photojournalism, said that photographers were often split into two categories before: those taking paid gigs and those who were just hobbyist shooters. Nowadays, the line is blurrier. Bregg says that advancements in camera tech have made it incredibly easy for the average person to take photos that would otherwise be limited to professionals. He adds that while things like rooftopping can be impressive, he’s not keen on the idea of breaking the law in order to stake out a better shot.

“It’s a generational thing, perhaps. I’m older, I’m more cautious. I believe in being more cautious. When you’re young, you want to take risks, you want to gamble, and the thrill of doing something like rooftopping is very important [to some people].

“The proof of that thrill is being able to take a picture. It’s one thing to climb, but being able to bring the proof back with photos is different. Some of that photography is very good, it’s very artful. I can envy the quality and the content, but I can’t envy what they did to get there.”

A Ryerson journalism student and photographer Chris Blanchette says that, like Bregg, he can understand the length some people will go to in order to one-up each other. While he doesn’t necessarily agree with the idea of breaking the law to access certain spots or get certain photos, as a photographer constantly trying to improve his craft, he gets the desire to do so.

“Because photography’s art, and I think with art, there’s only so many ways you can do something, I think what makes it better is that you’re improving on the way you do it,” he said. “I think the same is with photos, I mean for people who are going up there, every year I’ve seen a new perspective of something or the same shot done a different way so I don’t think you can hit a wall in any aspect of photography as long as you’re trying to innovate and always trying to stay ahead of everybody.”

This past weekend, two other photographers and I were trapped on the rooftop of that unfinished condo with a security guard diligently looking for any trace of us. With just a DSLR and a few lenses, we were able to capture everything from long exposures to portrait shots. When the shine of a flashlight caused us to dive to the floor, our fun was over. After hiding until the guard left to find backup, we slipped out the emergency exit and jetted off into the night with pounding hearts. A few hours later, I’d post the photos to Instagram, fully edited and ready to show the world.

“Someone sees your photo and they tag their friend in it, and then you’re out a few weeks later taking pictures with them”

Considering nobody else had accessed that roof in the past, I had an exclusive perspective and no competition to compare myself to. Something about it felt strangely cheap, like I had traded the skill of photography for the ability to stomach my fear of getting caught. Talking to other photographers in the city like Golding, it’s clear there’s a sentiment that the skill of photography has been devalued to some.

But Blanchette doesn’t think so. In fact, if anything, he thinks that the bar for what’s considered high quality has just been raised to a new standard. Noting how Instagram has allowed him to not only connect with more people than ever and share his photos to be critiqued by a much more diverse audience, Blanchette says that the app is much more beneficial than it is detrimental to his viewpoint as a photographer.

“Collaboration is awesome. Instagram is like its own version of networking, because someone sees your photo and they tag their friend in it, and then you’re out a few weeks later taking pictures with them,” he said. “I have friends that I’ve met just through Instagram who are really close to me now and if I hadn’t had Instagram I wouldn’t have been able to meet them. I think there’s a really tight-knit community with the people you meet.”

My first time ever rooftopping was January of this year. The metal of the doorknob was cold, even through my leather gloves. With a yank, the door flung open and I was greeted by the shimmering skyline of Toronto — an array of bright towers and street lights cluttered my view like a visual symphony. Despite my frozen face and shaking hands, I couldn’t pull my eye from my viewfinder. I snapped picture after picture, sometimes blowing my frozen breath into the frame of the shot.

As I look back at some of the photos still saved on my computer, I can’t help but notice how poorly shot they were. At the end of the day, the quality didn’t matter — the sight of the city was enough to keep me coming back for more.

With files from Emma Cosgrove

Leave a Reply