Graduating from Ryerson in 2010, Filipe Leite was broke and unsure of his next move. After two years of searching for an outlet, a single tweet allowed him to pursue the greatest endeavour of his life — a 16,000 km journey on horseback from Calgary to São Paulo, Brazil.

"Let fools laugh; wise men dare and win."

With those words, in 1925, Swiss writer Aimé Tschiffely set out alone on horseback to ride the 16,000 kilometres between Buenos Aires and New York City.

It was a story Filipe Masetti Leite had heard from his father a hundred times, who’d heard it in turn from his own father long before. A group of horsemen spend the night at a small bar in the grassy Argentinian lowlands, drinking and arguing to pass the time. How long to ride from here to New York? One hazards a guess — the others take it as a boast. They call it impossible, absurd. They drink and drink. The stakes get higher and higher, and the next morning one clops off with two short, stout Argentinian Criollo horses to prove himself.

"It was one of the most epic long rides of all time," says Leite. "I fell in love with the story. I never managed to shake it from my imagination."

Raised into a long line of Brazilian horsemen, he had learnt to ride before he could walk. He read reverently from the autobiographical Tschiffely’s Ride and dreamt of embarking on an epic, cross-continental journey of his own.

But after graduating from Ryerson in 2010, nothing seemed less possible. He was a broke journalism grad without connections or equipment. And living in downtown Toronto, it had been five years since he last rode a horse.

"Everything was against me," says Leite.

He made a pilot video pitching his plan and sent it to as many production companies across North America as he could. He called it Journey America and it was going to take him home, over the 12 countries and 16,000 kilometres between Calgary and his family’s ranch in São Paulo, Brazil.

Living a nomadic life and reporting it as he went, Leite would tell his story and the stories of those he met in real-time, online. It would be about more than physical endurance or equine prowess — his story would tell of the similarities between people of all nations, of the common thread of humanity.

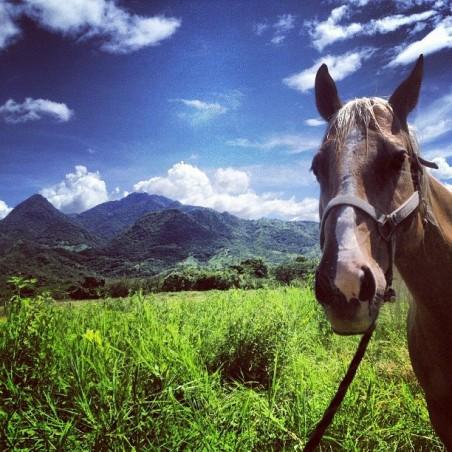

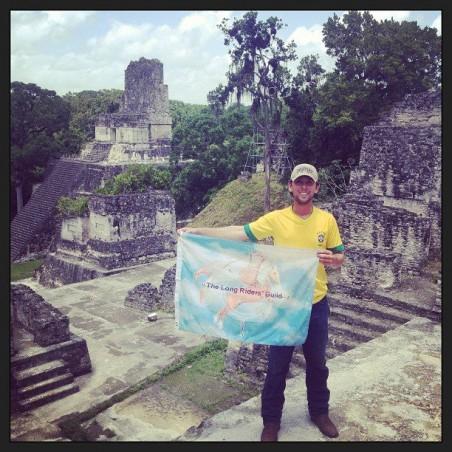

Photo Courtesy Filipe Leite.

But nobody bought it. No one took him seriously and for two years all he heard was "no."

He then sent a single tweet to influential video-journalist (VJ) Michael Rosenblum, who had trained reporters for the New York Times and popularized the role of VJ as a one-person camera crew. Rosenblum was in the process of starting a new channel called OutWildTV, and saw in Journey America a star for his show. Before Leite knew it, he was flown out to Nashville, enrolled in Rosenblum’s video boot camp and suddenly had much of the funding he would need.

Copper Spring Ranch in Alberta donated two Quarter Horses — Frenchie and Bruiser. Sponsorship started to snowball and two months later, thanks to a miracle tweet and the kindness of strangers, Leite set out on the longest ride of his life.

A Long Ride, as specified by the Long Rider’s Guild, spans a minimum of 1,000 consecutive miles (1609.34 km). Leite’s journey qualifies ten times over. It started on July 8, 2012 — the hundredth anniversary of the Calgary Stampede. With a procession of four RCMP musical riders to see him out, Leite begins his journey atop Bruiser, the calmer chestnut horse, while the wild and fair-haired Frenchie follows in tow, saddled with all of Leite’s possessions beneath a bright blue tarp. Leite estimates the total weight of his gear at between 40 and 50 kilograms — lighter than he is — and plans to live off only this and whatever he’s provided by those he meets along the road. He says this frightened him, at first.

"I cried a lot," he says. "I was scared to death. I had no idea where I was going to sleep that night — never mind the next two years ahead. And at the same time I was very happy to be taking the first step on my dream journey. It was a mix of emotions. I was leaving my girlfriend behind. It was very hard, but it was beautiful."

After a flurry of fanfare and media interviews, Leite rides from the stadium, kisses his girlfriend, fellow Ryerson journalism grad Emma Brazier — who will later support him from her van for stretches of the trip — and continues down the road.

"Most people expected me to be shocked or worried [about the trip], but I really wasn’t," says Brazier. "I knew he was just that type of guy who wanted to do something different in life ... and I believed in him."

"I cried a lot. I was scared to death."

The RCMP accompany him for a few more kilometres then double back to the stampede park and Leite goes on alone — although he never truly is. Deeply charismatic, disarmingly friendly, smiling, joking and laughing often with bright eyes under the brim of his white cowboy hat, Leite makes friends wherever he goes.

And on innumerable occasions during the long ride South, his new friends keep him going. Though equipped with a small tent and single-burner stove, there are things he simply can’t do alone. He needs to feed the horses — he affectionately refers to them as "his children" — which can consume up to 40 kilograms of food each per day. For this and much else he is dependent on strangers, which he says gave him new faith in people.

"You really get to see how nice and kind and loving people are, in all countries," he says. "Even the most dangerous countries in the Americas today."

He receives a number of gifts on the road through autumn of 2012. In Craig, Colo., after spending two days at the house of a man named Peter Lisker, Leite is given a container and a request: to carry with him the ashes of Lisker’s sister, Naomi, who had died months before. "I feel like you’ve come to my doorstep for a reason," Peter said. "I feel like you’ve come to take Naomi for one last ride."

"It made the hair on my arms stand up," Leite says. "He showed me pictures of her riding … and of course I said yes."

Photo Courtesy Filipe Leite.

In Montana, approaching Yellowstone Park, he’s given a small canister of pepper spray. Yellowstone’s Specimen Ridge has one of the highest concentrations of grizzly bears in North America and Leite has no choice but to cross it. While passing through, in a terrifying blur, a huge, dark grizzly barrels across the road in front of him.

"When I saw the size of the bear and the little [spray] can I was like, ‘what the fuck am I going to do with this?’" he says.

Come sundown, he finds himself with no water in the middle of a dense forest, forced to push forward until he and the horses can drink. He can barely see the ground in front of him as he manoeuvres his horses around the tall shadowed tree trunks.

Then he hears noises — crunching twigs and branches brushed by creatures moving all around him. He can’t see anything in the dark. He rides on yelling, continually, as loudly as he can. "The fear is running into them and startling them," he explains. "That’s when they kill you."

In Presidio, Texas — the last American city before the border — Leite receives his greatest gift thus far: the chance to ride alongside his father. "My dad inspired this trip," he says. "He read [Tschiffely’s Ride] to me as a kid. He loved the story. It was his dream to do this trip as a young boy, but he never had the opportunity."

But realizing a shared dream is not the only reason Leite’s father comes along. The drug trade controls northern Mexico and the cartel’s ominous presence hangs like a cloud over areas the pair will have to ride through. Leite’s father says he and his wife worried about this section of the journey in particular, and having two people is always better than one.

The pair ride together through the spring of 2013, over three months and more than 1,000 miles — enough to qualify Leite’s father as a long rider in the eyes of the guild. They cross the Chihuahuan Desert, camp out under the stars and eat beans baked over an open fire. They end their journey together at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City, and both describe their time together as if it was a religious experience.

"It’s something I’ll never forget if I live another hundred years. I’ll never forget that ride with my dad," Leite says.

Photo Courtesy Filipe Leite.

There are many parts of his two-year journey Leite won’t forget, some for the beauty and others for the fear.

Such was the case in the fall of 2013. After staying with a new friend in Guatemala, he then travelled south through the mountains into Honduras. With the highest murder rate in the world, Leite considers it the most dangerous country he’ll have to cross. The mountains themselves are a problem, muddy and washed-out from rain, but more concerning is that the whole border region is controlled by the cartel.

Luckily for Leite, his friend has a friend — a powerful drug lord on the Guatemalan side of the trafficking operation. And this friend has another friend — a neighbouring drug lord who agrees to meet Leite in a village on the Honduran side of the mountain pass.

The climb is steep, slick and littered with loose rocks. Sundown only makes things worse and for long stretches Leite must walk the horses up one-by-one, continually doubling back. Finally, well into the night, he and the horses make it to the small village on the other side and there is the drug lord, beer-in-hand, standing between a hole-in-the-wall bar and his own white horse.

"He threw me a beer and said, ‘Welcome to Honduras,’" Leite recalls. "And I chugged it back — I was so nervous. We just started drinking profusely."

Ten kilometres away is the compound where he’ll be staying, and he rides there through the dead of night, jittery from beer and flanked by cartel gunmen, some as young as nine years old, pistols slung on their backs.

When they arrive at last, Leite is amazed. Within massive cement walls the Honduran drug lord has built himself a personal paradise. A massive table, carved from a single slab of a once-mighty tree — an exact replica from Da Vinci’s The Last Supper — sits in one of the mansion’s many rooms. Above it dangles an ornate chandelier, one of six throughout the house. Plasma screens hang like paintings, one on every wall. There’s even a petting zoo.

During his two days in the compound, Leite gets to know his host, who will visit him periodically throughout Honduras ensuring his safe passage. Despite the gun-toting children, the violence and the drugs, Leite says he softened toward the man.

"I saw the humanity in him," he says. "He loved his children. He loved his wife. He came from a very poor family and started running drugs up to Guatemala when he was young — he travelled the same route I had travelled to go into the country. It’s hard to judge a man. When you’re born with no opportunity, what do you do? Do you pick up the gun ... or do you live like a slave?"

Photo Courtesy Filipe Leite.

Later, in the Honduran capital of Tegucigalpa, he’s startled by gunshots from the street below the window of his tiny hotel room. The hotel owner, in a drunken rage, fires six shots at his wife, who screams desperately.

"I could smell the gunpowder," Leite says. "I could taste it. I just felt so helpless, not knowing what to do for the woman as she yelled."

The fear drags on throughout the night. He imagines the man climbing the stairs to his room and murdering him — the hotel’s only guest, the only witness, who couldn’t have helped but heard the whole thing. He sits on the bed and stares at the door. He doesn’t fall asleep. Fortunately, the hotel owner was a bad shot and his wife was unharmed. In the morning, he saddles the horses and rides off, relieved to be leaving his hotel in Honduras.

In spite of everything, from grizzly bears to cartel kids to drunk husbands with guns, Leite considers the worst part of his journey down through the Americas to be the bureaucracy. Distrustful to the point of paranoia, border authorities stop him for days at a time, going over paperwork, medical records for the horses, seals, stamps and signatures.

His longest border crossing is his last, in the humid South American summer of 2014, east from Bolivia into Brazil. He and Brazier are stopped and the horses unsympathetically quarantined for 30 days.

"I was at the end and I had arrived on nothing," Leite says. "I was dying. My pants were ripped [and] my boots had holes. I was a mess."

"It’s hard to stay motivated two years into the trip," Brazier adds. "You’re just exhausted."

The cold sterility of quarantine weighs heavily on their spirits. Despite several daily medical tests the horses are required to endure, nothing is provided for them. Leite and Brazier have to hire an expensive veterinarian, as well as purchase netting and cleaning supplies for the horses’ stalls. Before long, the expensive quarantine ruins them and, literally penniless, they grow increasingly desperate as the horses face starvation.

"It’s like a mother not having food to give her child," Leite says. "It just kills you."

Turning back to social media as his last hope, Leite posted to Facebook about the ordeal, pleading for help from anyone who follows Journey America online. Within minutes, a Brazilian farmer offered to donate a truckload of hay. Another offered to drive it to the border. Others offer money for gas. Comment after comment comes in from people all over the continent, some who’ve never met Leite in person, offering whatever they can and, above all else, their sincerest support.

"It’s the power of social media," Leite says. "It’s very telling of our times."

"I was dying. My pants were ripped [and] my boots had holes. I was a mess."

Not only did it help Leite throughout Journey America — from securing funding in the first place to keeping his mother informed that he was, in fact, alive — it also allowed him to improve the lives of countless others. Through Facebook, he was able to secure a $3,000 sponsorship for a Mexican youth baseball team, as well as $500 for two boys with osteogenesis imperfectica, also known as glass-bone syndrome.

"It’s amazing what you can accomplish through this medium that some people like to trash, saying it’s separating us," he says, believing nothing to be farther from the truth.

At last, on Oct. 10, 2014, after 803 days on the road — over mountains and marshes, deserts and snow — Leite arrived in his hometown of Espirito Santo do Pinhal in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. He rides into town joined by more than 500 others — a slow, happy stampede. He looks into the welcoming crowd and sees familiar faces: family friends and childhood pals all grown up. He greets the mayor and is showered with gifts. That night, the town throws a welcoming party.

Photo Courtesy Filipe Leite.

After his glorious homecoming, in a quiet moment Leite takes the container with Naomi’s ashes out to the pasture where the horses laze, basking in their well-deserved retirement. He removes the lid and thinks of Naomi, of everything they’ve been though together since Craig, Colo.

"As I got farther on the trip," he says. "I started to feel like Naomi was a guardian angel."

He then spread the ashes on the pasture, throwing them from the container up out into the air.

"I thought they would just drop," he says. "But they rose like a cloud and went up to the sky until they disappeared. It was a really beautiful moment."

Now settling down to life on his family farm, Leite will soon have his journey told in a Rosenblum-produced documentary. He’s also 160,000 words into the first draft of a book — his very own Tschiffely’s Ride — to be published later this year.

"I started to feel like Naomi was a guardian angel."

For more information, here is Journey America, where Leite's video updates were posted, and this is Leite's instagram profile.