By Graeme Smith

The last time Ronald L. Soskolne invented a scheme for the land around Yonge and Dundas, the year was 1976. Soskolne had been chief city planner for only a few years. He boldly rewrote the rules for the street, deciding that buildings near the intersection should be kept small, despite the area’s location near downtown skyscrapers. He said people would be drawn by the “mix of taverns, record shops, clothing stores, body-rub parlours and pinball arcades.” He thought the sidewalks would be crowded day and night.

But Soskolne was wrong. He left the city planning department soon afterwards to pursue a career in real estate development. While he was gone, the area — which he thought would flourish — deteriorated into a seedy jumble of discount stores and porn shops. Now, most evening pedestrians on Yonge are drug dealers, panhandlers or vagrants.

The little shops that Soskolne described in his city plan as “vital, noisy, and flamboyant” have become cluttered, messy, and cheap. Many owners of the properties around Yonge and Dundas don’t own the businesses there, so they let their buildings grow shabby.

But Ron Soskolne hasn’t forgotten Yogne and Dundas. He isn’t discouraged by the deterioration that followed his last great vision for the area. After developing construction projects around the world, he is going to change Toronto again.

It’s a grand scheme: a public square, new stores and an American-style cinema megaplex. It will transform Yonge and Dundas into a bustling place of bright lights that will attract wide-eyed tourists.

Soskolne originally wanted to demolish Ryerson’s parking garage and put vendors along Victoria Street. Some vigorous negotiating by Ryerson made him change his mind.

But Ryerson’s objections were among the few forces that could make Soskolne alter his course. He relentlessly pursued what he failed to achieve last time: making Yonge and Dundas a vibrant attraction at the centre of the city.

This was more than just another project for Soskolne, but sometimes he had too much enthusiasm. Although he denies it, his paper trail suggests he made deals with companies before city council asked him to begin selection companies for the development — even before council had approved the idea of any such project.

Why was Soskolne so enthusiastic? After all, he was just a consultant, a hired gun, paid to clean up Yonge Street. But this was not about money. Soskolne started his career in Toronto. When he returned after two decades, a veteran of a dozen other downtown projects, he saw the effects of his original plan for Yonge and Dundas. It wasn’t a pretty sight.

Soskolne is back, and this time he’s going to do it right.

After his stint as chief city planner in the 1970s, Soskolne moved on to much bigger things. Real estate developer Olympia and York (O&Y) hired him to work on urban development projects. His first job was creating Queen’s Quay on Toronto’s harbourfront, but soon his assignments took him further away – to Boston, Los Angeles, Dallas and San Francisco. Eventually promoted to O&Y’s senior vice-president of planning and development, Soskolne helped create London’s Canary Wharf and New York’s Times Square redevelopment. When O&Y collapsed, Soskolne continued to work for its owners, the powerful Reichmann family, scouting development opportunities in Asia and Mexico.

Many of Soskolne’s international projects were Urban Entertainment Centres (UECs). A growing trend in North America, these developments concentrate movie theatres, theme restaurants and retail stores into one area, creating a kind of urban Disneyland. UECs are typically anchored by a main attraction, usually a large movie theatre. The idea is to provide people with an all-in-one destination for dinner, movies and shopping.

During his O&Y years, UECs became Soskolne’s specialty. He worked on the Times Square development in New York, a project that involved expropriating properties along 42nd Street to make room for entertainment venues such as a 25-screen movie theatre operated by AMC Entertainment International. The project also involved cleaning up the square and adding more exciting signs.

Four years ago, Soskolne brought his expertise back to Toronto. He founded a consulting firm that co-ordinates developments for corporations such as Shell Oil and Walt Disney. Soskolne chose a building on Yonge Street for his offices.

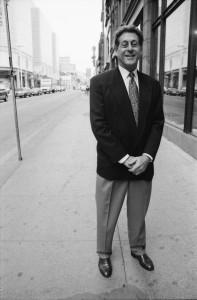

When he moved in, Soskolne’s building was home to The Silver Rail, a stately restaurant and bar. Now the hallways are choked with drywall dust as the Silver Rail is being torn out and replaced with a trendy retail outlet (which will include a nine-foot tall fake moose). Looking out the window of his office the Eaton Centre stands like a fortress, dominating the view. Although his services involve planning and management, Soskolne’s offices show architectural training. Large wooden doors open to spacious rooms whose hardwood floors are awash in sunlight. The colours are muted; the artwork and furniture are tasteful. It’s sophisticated and practical.

Soskolne presents himself in the same way. He is cordial and speaks with a subtle accent, which grows stronger whenever he talks about his work in foreign countries. His brown shoes are freshly shined. Everything I say make him chuckle. Seated at his desk, he leans forward, smiles and raises his eyebrows, as if to say, “I am humouring you. Now proceed.”

He had reason to be in good humour — the most important project of his career is nearly a done deal.

The deal began several months after Soskolne started his consulting business. His old boss, former Toronto Mayor David Crombie, introduced him to the Yonge Street Business and Residents Association (YSBRA). The association explained their problems: rising crime in the area, failing property values, garbage on the street, ugly facades. Could Soskolne help? He thought so.

The YSBRA hired Soskolne in march, 1996, and paid his fee with most of the $100,000 they had raised in donations and a $150,000 grant from the City, Officially, he was a general consultant: he was to look at Yonge Street and find a way to improve it.

But Soskolne says the YSBRA needed him specifically for his experience with large development projects. “Because of the work I had done on UECs, I was more aware of the kind of opportunity that existed for Yonge Street,” he says. In testimony to the Ontario Municipal Board about the project, YSBRA member. Arron Barberian admitted that Soskolne’s assignment wasn’t entirely open-ended. He said Soskolne’s job was to change the area “as was done in Times Square.”

The situation at Yonge and Dundas was similar to that of New York’s 42nd street. Both had problems with crime, shady businesses and street people. In both cases, a coalition of city officials and local business owners decided something had to change. In New York, the solution was to expropriate properties, demolish buildings, and invite big entertainment and retail businesses into the area. It seems Soskolne was aware that there could be a similar solution for Yonge and Dundas.

Soskolne analyzed Yonge Street that spring. W hat he found was nothing like what he had envisioned in his 1976 city plan. Between 80 and 90 per cent of the retail tenants between College Street and Queen Street held short-term leases. Crowding the street were 29 discount or dollar stores. He talked to business and property owners and discovered that although they all agreed something had to change, many were jealous of each other and wouldn’t work together. Worst of all for Soskolne, no developers were interested in new projects in the area.

The YSBRA was attempting to change the situation with improvements such as cleaning the street and adding garbage cans on the sidewalks. But Soskolne recognized something more dramatic needed to happen. The July 24, 1996 meeting at City Hall of the steering committee for the Yonge Regeneration Program (including YSBRA members and city officials) started off as usual, with a discussion of street cleaning and garbage collection improvements. But when Soskolne spoke, he changed the course of the improvements entirely. “There needs to be full commitment by the City to an aggressive redevelopment,” the minutes show he said. He also recommended two specialists be hired: a legal consultant for economic analysis. Soskolne told the committee everything about the redevelopment program must be kept confidential, and the best way to do so would be to form a secret sub-group to manage the whole process. The committee agreed to everything. Three members were chosen for the sub-group: Soskolne: YSBRA chair David Bednar, and City Councillor Kyle Rae.

Soon after Ryerson signed a deal with the city, all the players involved gathered for a photo opportunity.

Soskolne’s project developed in secrecy for four months. During that time he collaborated with city planners to develop a basic concept, and made regular reports to Rae and Bednar. Because Soskolne had once been chief planner, he worked well with the men at the planning department. Their vision for Yonge and Dundas included a new public square, a movie cinema and development of other lands. They presented the idea to city council — just the idea, no specifics — on Dec. 10, 1996, and made the plan public. Council approved the idea in principle and asked them to start selection a developer and a cinema operator to be the anchor tenant.

But when Soskolne talks about how he selected the anchor tenant and developer, a confusing and contradictory story emerges.

His first story is straightforward: the process happened from the time council approved the idea in December, 1996, until council approved details of the project in May, 1997. During that time Soskolne negotiated with the only two cinema operators who were interested: Cineplex Odeon Corp. and AMC Entertainment International Inc. AMC offered better terms, so it got the deal.

Soskolne says he discussed the idea with both companies before the council’s December approval, but he says the talks were just to make sure they were interested. When asked whether he meant Cineplex was still in the running after December, Soskolne says “Oh, you bet.” He remembers reading a proposal from Cineplex after December because he spent a weekend that winter in Panama and recalls sitting beside a pol reading the hefty document.

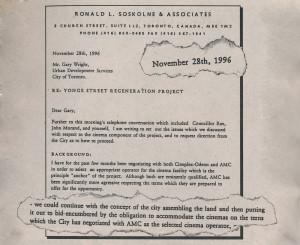

Then I show him a letter he wrote to a city planner, dated Nov. 28, 1996. That means he wrote the letter when Cineplex was supposedly still in the running, before council had heard the proposal and asked for companies to be selected. The letter, which The Eyeopener obtained from the Ontario Municipal Board, reads: “I have for the past few months been negotiating with both Cineplex-Odeon and AMC, in order to select an appropriate operator for the cinema facility.” It adds that AMC has been “significantly more aggressive” than Cineplex in these negotiations.

In the letter, Soskolne suggests the city skip the open bidding process for land developers, and instead “assist AMC to put together the required land” with PenEquity Management Corporation, AMC’s preferred developer. Soskolne said an open process to select a developer for the cinema would be difficult because AMC wanted to work with PenEquity — a bidding process would be “encumbered by the obligations to accommodate the cinema on the terms which the City has negotiated with AMC as the selected cinema operator.” In other words, AMC had been “selected” and PenEquity was considered the best option for a developer. The deal was essentially done — before council had even heard of the idea.

Soskolne takes the letter. He frowns, sitting back in his chair. He holds the paper in front of his face and reads. Sighs. Reads it again. Walking to the other side of the office, he picks up his glasses and scrutinizes the documents a third time. When he is finished, he seems to have difficulty choosing the right sentence and makes several false starts. It has been more than five minutes since he last spoke.

“Just a second. I think I’ve got my dates mixed up. Because I’ll tell you why.” He pauses. “When I was in Panama I had a serious problem with my back. I had surgery for that in December ’96. I hadn’t had that surgery yet [in Panama].” Another long pause. “But these negotiations were up and down and on and off,” he says, waving his hand vaguely.

Soskolne explains that the deal with AMC mentioned in the letter did not exist, that he was just anticipating a deal sometime in the future. He says the phrase “terms which the City has negotiated with AMC” means he anticipated negotiating terms with the company sometime afterwards.

But Soskolne was not alone in “anticipating” a deal. Just four days after he wrote the letter, AMC sent a formal offer to lease to PenEquity for a 20-24 screen theatre to be built on top of Ryerson’s parking garage. The offer came before any development at Yonge and Dundas was approved in principle by city council.

At the time, Soskolne says, he and city planners were torn between expropriating the land and putting it up for bids by developers or simply expropriating the land for a specific developer. “The end result was a sort of hybrid between the two options,” he says.

When the city requested submissions from developers for all the project sites in early 1997, there was a warning: the land around the Ryerson parking garage — the cinema site — might not be up for grabs. This didn’t’ stop half a dozen other developers, including the owner of the Eaton Centre, from submitting their qualifications as developers for the cinema. The city’s next move was in May, 1997, when council held a closed-door meeting to approve project specifics. Part of the proposal was to expropriate six properties on Yonge Street negotiate with Ryerson fro the air rights over the parking garage, “and sell all of it to Pen Equity [sic] Management Corporation.” The other developers would be kept away from the cinema site, and asked to submit proposals for the rest of the project. Council approved the plan.

Soskolne says he didn’t select a cinema operator before city council heard on the project Dec. 10, 1996 – but he wrote this letter before that date mentioning a deal with AMC.

Although he acknowledges his role as the visionary bringing a massive movie theatre to downtown Toronto, Soskolne says it is only natural. “It is important to understand that this was going to happen in Toronto anyways,” he says.

It is happening in other parts of Toronto already. Sony of Canada Ltd., the new owners of Cineplex, are considering the corner of Bay and Dundas for their own huge theatre complex. In the meantime, Cineplex is renovating Varsity Cinemas, adding eight screens, a cafe and aquarium. Canada’s other major theatre chain, Famous Players Inc., didn’t negotiate for a place in the Yonge and Dundas project because they have already begun working on another huge theatre, Festival Hall. Just south of the CITY-TV building at Queen and John Streets, Festival Hall’s 14 movie screens, restaurants, bars, bookstore and video arcade are scheduled to open this spring.

The trend towards gargantuan theatre complexes began in Dallas in 1995. That’s when AMC opened its first 21-screen behemoth in a warehouse district of the city. Its unexpected success sent theatre chains all over North America scrambling to copy AMC’s example.

Since Dallas, AMC has built more megaplexes than any other company. Revenue from these new theatres is expected to account for 73 per cent of AMC’s total revenue by the year 2000. The company is growing aggressively: last year it earned $750 million (U.S.), and analysts expect it to earn twice as much by the year 2000.

AMC’s recent expansion has included an aggressive sweep northward into the Canadian market, using PenEquity as their preferred developer. Together they are building 13 megaplexes in Canada, including ones in Oakville, Whitby, Kanata, Etobicoke and Mississauga — all with 24 to 30 movie screens, restaurants and retail stores udner tehs same roof. Work has actually begun on two of these sites. But until recently, AMC lacked a foothold in Canada’s largest market: Toronto.

AMC has wanted to build a theatre in Toronto for a long time. In 1993, PenEquity president Glenn Miller stood on the roof of the Eaton Centre with the chairman of AMC International. The men looked out over the east side of Yonge Street, wind teasing their grey hair. From that height, Yonge looked like a cluster of toy houses swept up against the monolithic shopping malls warmed by ant-sized pedestrians. AMC’s chairman gave Miller a simple instruction. “AMC needs to be here,” he said.

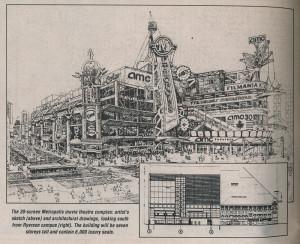

The theatre at Yonge and Dundas, named Metropolis, will be the centerpiece of AMC’s Canadian development. PenEquity will complete construction in late 2000. Metropolis will be seven storeys tall, with three underground levels. It will boat a floor area of 55,729 square metres. The cinema will occupy 60 per cent of the space and the rest will be retail. There will be 30 stadium-style movie theatres with seating room for 6,000, designed to mimic the comfort of first-class airline seats. A cavernous glasses lobby will look south, across Dundas Street, into another new development — a public square.

The three other sites in redevelopment are less clearly defined at this point. The buildings north of the Hard Rock Café and south of the new Metropolis will be demolished to create a public square and underground parking garage. The City will spend $2.5 million to make the square the centerpiece of the project. It will probably include a ticket kiosk, new subway entrance, connection to the city’s underground PATH and possibly outdoor art. A design for the square will be chosen this December.

East of the square, this city is negotiating with the owner of Hakim Optical at the corner of Dundas and Victoria Streets about a development that could combine Hakim’s property with this city’s adjacent lad not the north. Across the street, Bob Sniderman is negotiating with the city to develop the Salvation property as an expansion of his Senator restaurant.

Atop the Atrium on the Bay, owners are planning to build a media board, like a miniature version of the one in Times Squares. That sign will glow alongside dozens of others in the area — Metropolis has already received a bylaw adjustment to allow more signs — in an effort to create an exciting atmosphere.

Even Ryerson is considering a new sign, facing Lake Devo from the side of the Metropolis building. The display screen would flash campus messages and display New Media students’ says campus planner Manuel Ravinsky.

If you aren’t looking forward to elbowing your way through hordes of moviegoers on your way home from school, remember: if it weren’t for Linda Grayson, it could be worse.

It is June 1996 when Grayson, Ryerson’s v.p. administration, first hears of the project. She is attending a convocation luncheon — Ryerson is giving Governor General Romeo LeBlanc an honourary degree. It’s a dignified crowd, all polished shoes, cufflinks and perfect hair, assembled in the newly renovated Pantages Theatre. Grayson notices City Councillor Kyle Rae looking at her from across the room. He crooks his finger at her in a “come hither” gesture. Moving across the room to greet him, she raising her eyebrows questioningly.

“Linda, we want your parking garage,” he says.

Grayson laughs, but she also agrees to discuss the matter later.

Formal negotiations began that September, during the project’s secret planning period, when Sosklne sent Grayson a letter requesting acquisition of the site. Grayson fired back an extensive list of concerns and conditions. They began negotiating.

“Sometimes Ron [Soskolne] and I didn’t get along,” said Grayson. At one point, Soskolne wanted the plan to include vendors’ stalls along Victoria Street, but Grayson flatly refused. “He assured me they would be high-end kiosks,” said Grayson. “I still said no.”

Negotiations dragged on for nine months, Soskolne still wanted the garage, but he wasn’t willing to pay enough to compensate Ryerson for the lost revenue from parking fees. Grayson demanded compensation for things such as the damage increased pedestrian traffic would inflict on Ryerson’s landscaping.

Ryerson eventually signed an agreement with the City of Toronto last September. This deal will form the basis of a contract with PenEquity when they buy the land expropriated around the parking garage. The deal states:

Ryerson keeps the parking garage, but loses the air rights. PenEquity will build on top. The bookstore also stays.

Ryerson can use 12 theatres as classrooms from 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. for 15 years, with the option of a five-year renewal afterward. This was Grayson’s idea. “These will be good lecture spaces, where the sightlines are good — not like some of our old lecture theatres where you can get stuck behind a pillar.”

Ryerson gets $1 million in cash to cover legal fees, possibly for constructing a gateway to Ryerson and to allow accidental construction damage to be repaired immediately without waiting for an insurance claim. This also covers minor complaints such as damage to Ryerson’s shrubbery.

PenEquity guarantees the revenue of the parking garage will be at least $500,000 greater a year for 20 years including the construction period. The city will partially insure this arrangement.

The whole package is worth an estimated $17.1 million to Ryerson.

Although Grayson and Soskolne didn’t always agree, she said she was impressed by his fervour for the project. “He was so committed,” she said. “It captures your attention. This wasn’t just another development for him.”

The 30-screen Metropolis movie theatre complex: artist’s sketch (above) and architectural drawings, looking south from Ryerson campus (bottom right). The building will be seven storeys tall and contain 6,000 luxury seats.

Soskolne laughs when I told him about Grayson’s assessment. “I love this city,” he says.

“I live right downtown. I’m concerned about its health. And this part was ailing.” He looks at the walls of his office, which are covered with framed drawings of his other projects all over the world. “The project is as much a labour of love as just another professional assignment,” he says.

Leave a Reply