By Renata D’Aliesio

It was called the silent phase. A time for the University of Toronto to finalize its fundraising leadership and work the kinks out of its multimillion-dollar campaign. A time to build stronger ties with well-known, deep-pocketed friends who would not only hand over their chequebooks but sway others to do so. The Group of 175 was assembled from from prominent volunteers such as former Ontario premiers William Davis, David Peterson and Bob Rae, film director Norman Jewison and General Motors president Maureen Kempston Davis. Together, they would help the university transform the face of philanthropy. During the silent phase, which began May, 1995, and ended almost two-and-a-half years later, U of T raised $275 million, more than half of its minimum goal of $400 million. WIth its pockets lined, the university geared up for the campaign’s public launch in September, 1997.

Since 15 per cent of the Ontario government’s university funding was eliminated in the past two years, universities will not be able to maintain academic standards without embarking on ambitious fundraising campaigns. In 1997, U of T had $54 million of its $373 million operating grant cut. It was the largest cut the university ever absorbed in a single year.

The eight-day extravaganza, dubbed “Great Minds Week,” included a black-tie gala at the Sheraton Centre Hotel, ribbon-cutting ceremonies and lectures by renowned professors and Nobel Prize winners. Banners with 39 smiling faces of great minds such as Roberta Bondar and Margaret Atwood were hung from lamp-posts around campus. The purpose of the promotional week: to put a public face on a monetary campaign.

Bu even before this period of fanfare and hoopla, U of T’s fundraising campaign had already secured its place in Canadian history, raising more money than had any other public university. No university had ever endeavoured such a bold financial goal. Until now, the largest campaign was a $262-million effort in 1993 by the University of British Columbia. In 1996, McGill University also surpassed the $200-million mark with its Twenty-first Century Fund.

The Right Formula For Finding Dollars

However, rather than look on with envy, most universities welcome U of T’s ambitious campaign because it sets new fundraising standards. While campaign goals of more than $400-million may become the norm amongst they big schools, duplicating U of T’s success will not be easy. The campaign, which is expected to wrap up in time for the school’s 175th anniversary in 2002, has all the right pieces in place. A well-liked president with a flair for oration. A campaign leader who has strong ties to the university and a wealth of fundraising experience. A large, affluent alumni with a willingness to give and solicit others to do the same. A healthy economic climate and recent changes in the tax laws that allow for larger tax breaks on donations. And a school that’s not afraid to spend money to make money.

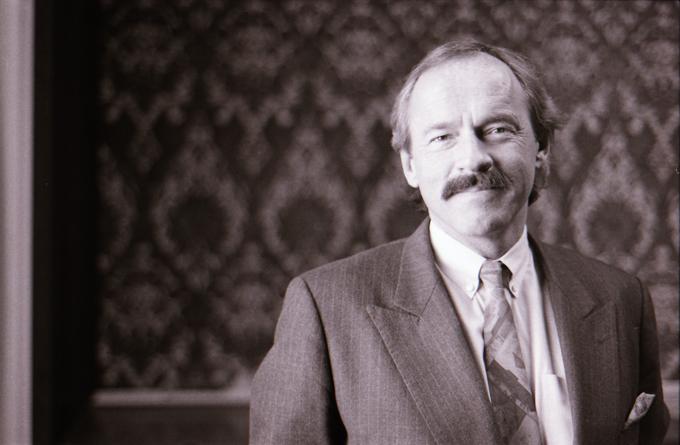

Undoubtedly, U of T’s fundraising success can be in part attributed to Jon Dellandrea, the man the school’s president, Robert Pritchard, handpicked to lead the campaign. The U of T graduate and former Varsity Blues linebacker has been the school’s v.p. chief development officer since 1994. When asked how long he’s been in the fundraising business, Dellandrea says, “I have spent my life doing this.” He worked on U of T’s first modern campaign, raising $25 million in the mid-1970s. And after stints at the University of Waterloo and Mount Sinai Hospital that included fundraising work, the man who holds three U of T degrees says he’s happy to be home.

“It’s great coming back,” he says with a proud smile. “I have a tight personal connection with the university.”

Dellandrea leads a team that includes 45 employees representing every department and faculty. The priorities they target were formed by the school’s 1994 White Paper, which focuses on academic objectives and strategies for the next millennium. The school’s 29 divisions, colleges and faculties were asked to identify their needs. The wish list includes: 175 endowed faculty chairs, fellowships, student scholarships and bursaries, a new health sciences centre, an upgraded library, laboratory and classroom equipment. The price tag — $625 million. “It’s not good enough to be the best in Canada,” says Dellandrea. “This campaign will help us cement our place as one of the best public research facilities in the world.”

U of T Expected to Raise Goal in May

So far, with a $23 million campaign budget, more than $415 million has been raised. On May 4, a new financial goal is expected to be announced that will bring the university closer to the $600 million plus sum outlined in the White Paper. Eventually, through the university’s contacts and friends of the Group of 175, all of U of T’s 320,000 alumni will be politely pressured for money. A customized menu of donation options with projects to support and chairs to endow will be presented to prospective donors. Just last Friday, Dellandrea secured a commitment of more than $1 million from a graduate for the transitional year program, which is designed to help students trying to get into university because in his business, the donor has “gone out of his way to hire workers who don’t always have the necessary skills at the start.” The deal is expected to be announced in the coming weeks.

U of T’s campaign budget, the biggest in Canadian university history, has allowed Dellandrea and his team the luxury of meeting with prospective donors in cities such as Hong Kong, New York and London. In 1996 and 1997, Dellandra and about a dozen U of T fundraisers and researchers flew to Hong Kong for about a week on fundraising, promotion and recruitment tour. On one trip, the team returned with $12 million in donations, half of which were raised in the first five days.

Along with the university’s main financial goal, a separate target of of $200 million bequests has been set. Will money is, for the most part, uncharted territory in Canada. “It’s an important part of our future,” says Dellandrea. “As our older alumni make plans for their estate, we are asking them to consider including us.”

Academic Concerns With Rise in Donations

Although U of T’s fundraising drive has been impressive, critics say the financial gains have cost too much as academic priorities are being set by donation dollars. At U of T, as an added donation incentive, naming opportunities are presented. Departments and institutes are renamed for between $5 million and $25 million. Divisions and centre go for between $2 million and $10 million. And the going rate for a classroom is $25,000.

“The fact that [U of T] is able to raise so much money is great,” says Deborah Flynn, president of the Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations. “But the increasing dependence on private funding means the university is losing autonomy.” About 50 per cent of the university’s gifts have come from foundations and corporations — the other half from individuals.

“We’ll continue to keep lobbying the government for more funding,” says Dellandrea.

“But we can’t just sit back and wait. We have to plan a future under the assumption there will be no increase in support.”

Leave a Reply