By Naomi Powell

Outside a boarding house near Pembroke and Dundas Streets in one of Toronto’s seediest areas, Paul Kaups laughs with a couple of men. The house is non-descript, its bricks painted a dismal grey, its small yard enclosed by a chest-high wooden fence. A hefty man wearing big, square, horn-rimmed glasses, a Survivor T-shirt and a greyish goatee bustles through the gate to show Kaups a black sweatshirt he is trying to sell. He turns the sweater over in his hands, revealing fingertips covered in raw, open sores. Kaups doesn’t flinch.

“I don’t even notice things like that anymore,” he laughs. He says the sores may be burns from smoking cigarettes or crack cocaine.

Paul Kaups, 30, is a student nurse in the undergraduate program at Ryerson. Last April, he began a summer placement with Contact — St. Michael’s Hospital’s mental health outreach service. The placement ended in September, but he still helps out four days each month.

“I had thought about nursing in school,” says Kaups. “But that was just something male students did then.” There are only a handful of men in Kaups’ nursing classes. If he was uncertain at first, these days Kaups is planning to take his nursing further and return to school to become a nurse practitioner. Today, dressed comfortably in a green fleece sweater and jeans, he greets tenants of the house with a ready smile.

“I choose to work with mental health cancer patients because they need a lot of emotional support,” he says.

The Contact program sends nurses, psychiatrists, addictions counsellors, and other professionals into the streets to work with mentally-ill people. The serve patients in the downtown area between Pape and Bathurst. A large number of these people called “clients” by the Contact team, are homeless or living in government-funded apartments and boarding houses. They’ve usually referred to the program by hospitality.

“The worst clients are the ones you hear yelling on the street,” says Kaups, who is paid $18 an hour for his work. Kaups says the majority of Contact clients suffer from schizophrenia, an illness that causes delusions, institutional behaviour and withdrawal from social activity.

“The program makes sure they have someone to watch out for them, you know, help them with whatever they need.” This could involve picking up clients’ prescriptions, cleaning their apartments, collecting their welfare cheques, and even testifying for them in court.

“Some people see this kind of nursing as soft,” says Kaups. Unlike traditional emergency room or hospital nurses, outreach nurses treat patients in their own environment. They observe what their patients deal with on a day-to-day basis and how it affects their mental health. “Community nursing gets a bad rap because you don’t always skills like taking blood pressure and doing chest assessments,” Kaups says. “We use a whole different set of skills. This is a whole different kind of nursing.”

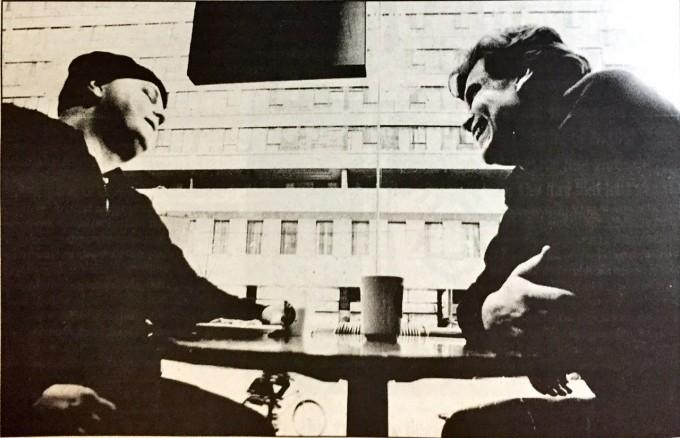

Street nurse and third-year nursing student Paul Kaups, above, attends to wounds on cold downtown streets Photo: Tim Fraser

It is the kind of nursing that once involved pulling a patient from an apartment he hadn’t left in days. Kaups and the Contact team had heard the man was acting strangely on the street, staying as far away from people as he could.

“He was schizophrenia and with him the illness manifests itself through not trusting anyone and hiding out in his apartment.” When Kaups and a doctor arrived at the Carleton Street apartment, the man wouldn’t answer the door. A worker in the complex had to let them in.

“It was really dark. We are pretty sure he’d been in there for about six days and the smell of body odour was awful so we knew he hadn’t washed in a long while,” says Kaups. While there, he found a drawer full of “meds,” or prescribed medication, and realized the man hadn’t taken his pills in weeks.

“We found him lying in his beds, yelling at us to go away,” he says. “He was curled up under a comforter and when we pulled it back he was just skin and bone. The guy had lost at least 20 pounds. There was nothing that even resembled food in the kitchen.” Kaups took the man’s blood pressure, temperature and pulse and then brought him to the hospital.

“It’s like any job. You always have bad days,” says Kaups. “If something needs to be done, you just do it.”

In the basement kitchen of the boarding house at Dundas and Pembroke, Ky Na, the 28-year-old manager, cleans a mess of crumbs and spilled coffee from a small café table. He settles into his chair, dressed in a grey cotton T-shirt and jeans. Na has been working in the boarding house since 1992 and says it would be difficult to run the place without the Contact team.

“We’re not really here to deal with a crisis,” he says, “and we’re not funded to have nurses on staff.” The boarding house is a for-profit organization and the residents are placed there by government agencies. Room and board of $543 per month is withdrawn directly from the residents’ disability cheques. “We provide a room and food, but if we think a tenant is suicidal or depressed, we call a Contact worker. They have to be very patient to handle things.” He grins and leans back. “Paul is very patient.”

Kaups is the youngest of four children, born while the oldest child was still in diapers. When the kids were old enough to look after themselves, his mother started a daycare in their home. Even with all of those children around, Kaups can’t remember his mother yelling once.

He describes both of his parents a “devoutly religious.” His father became a Baptist Minister ten years ago and as children, Paul and his three siblings went to church twice a week, sang in choirs and were always in Bible study groups. It’s a lifestyle that Kaups has let go. “For me spirituality is just doing what you believe in,” he says.

Kaups’ family moved to Toronto from North Carolina when he was 14. In 1992, he left a physical education program at York University after his first year and took a laboratory at Seneca College. After earning his diploma he moved to North Carolina and found a job in a lab.

“I was mostly washing glassware and counting virus cells,” he laughs. “I was glorified dishwasher making $15 an hour. They would hand me this vat of virus cells and I would stand over a microscope counting them.” Kaups left the lab after one year and returned to Canada in 1996 where he enrolled in Ryerson’s computer science program. But he couldn’t face a future in front of a computer terminal and went into nursing at Ryerson in 1998.

“I need to have human contact in my work. I need to be in a situation where there’s always something going on,” he says. Kaups will complete the program next year.

But Kaups is not completely immune to the bad days. It took him a while to develop the thick skin he needs to deal with such emotional situations. “At first, I thought ‘Oh this is awful,’ but you get a little desensitized. I don’t have that reaction.”

“Sometimes you want to do so much, but you feel helpless.” One of the hardest parts about the job, he says, is setting boundaries.

“I want to help these people but I can’t get personally involved because I could lose my objectivity. Maybe the things I want for them aren’t what they want. If I keep pushing them to take their medication, they can get frustrated with me and then I miss chances to help them in other ways.”

In the basement kitchen of the boarding house, a handful of residents are scattered, leaning against mauve walls, sitting behind the small, pink café tables. An old TV is bolted to the ceiling in the corner, playing music videos. A cloud of cigarette smoke hangs under the low ceiling. At 6 p.m., Kaups says goodbye to Na at the little blue door and climbs the narrow cement steps back into the yard.

“This gets hard sometimes,” Kaups says. “I’m glad to go home after today.”

Halfway up the steps, the door opens again and a man in a pink shirt pokes his head out to say another goodbye.

Paul, you’ll come to see me right?” Kaups promises he’ll be back.

Leave a Reply