By Lisa Cumming

The Ryerson women’s hockey team was facing Guelph University at the end of January 2012. When the puck dropped, the fifth game of their season began. As Paulena Jakarsezian skated across the ice, she quickly glanced back to survey her surroundings. A second later, she collided with a teammate. The feeling of impact came hard and fast. Her teeth cracked together; she wasn’t wearing a mouthguard. The incident left her with her first (and her worst) head injury to date.

After that concussion—one of eight throughout her four years of playing hockey at Ryerson—Jakarsezian started grinding her teeth at night. Once, she woke up to find missing fillings. Another morning, a shattered tooth.

Immediately after a concussion, Jakarsezian used to continue to play without allotting herself time for a safe recovery, or reporting her injury. A hockey rink is extremely bright and loud—conditions that are not suitable for someone with a brain injury. She sought out Advil as the answer to mind-numbing headaches, but often found herself spacing out during games; what felt like three seconds of staring at the ice turned out to be three minutes on the clock. She had trouble remembering where in the lineup she was and who she was supposed to replace.

Her last concussion, in January 2016, was the one that took her off of the ice completely—and the one that took the largest toll on her emotionally. “You think you know what anxiety is, then you get a concussion and you really know what anxiety and clinical depression feels like,” she says.

Alongside her anxiety, Jakarsezian also experienced short-term memory loss and exhaustion. She says at one point, her emotional and mental state got so bad that she had to stay home for a month, locked in her room. She could hardly string a sentence together and she struggled to describe her emotions. “When you break your leg you can heal it again, when you hurt your brain it’s not the same,” she said. “People with concussions end up killing themselves.”

After that concussion she started grinding her teeth at night. Once, she woke up to find missing fillings. Another morning, a shattered tooth.

Young athletes are under a tremendous amount of pressure to succeed in their sport, and like Jakarsezian, they sometimes prioritize their athletic prowess over their physical and mental health, which can be more interconnected than perceived. A recent study done by the Canadian Medical Association Journal concludes that adults who suffer from concussions are three times more likely to be at risk of suicide, and many more suffer from depression and anxiety.

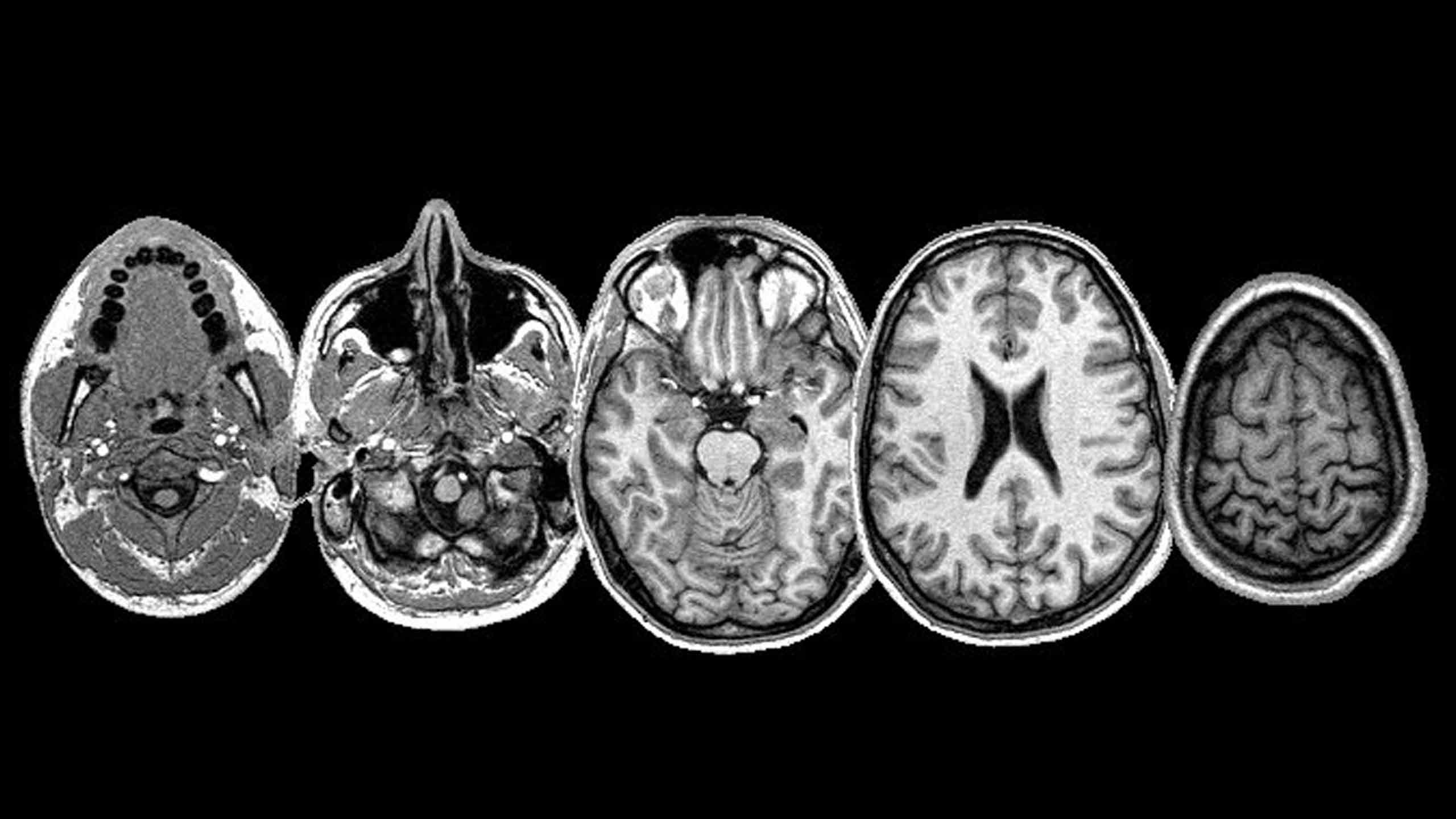

While the connection between brain injuries and mental illness used to be unclear, research from the Radiological Society of North America highlights technological developments that have allowed doctors to gain a better understanding of the relationship. By using MRIs to compare patients who had experienced mental illness post-concussion and those who hadn’t, they were able to detect unique brain patterns and abnormalities in the white matter—the substance that helps sends messages through the brain—with those who had. Patients who were depressed had decreased functionality of their white matter and those with anxiety had impaired white matter function.

For Jakarsezian, concussions never seemed like a serious issue. She would always reassure herself that it “wasn’t as bad” as the last one. Unfortunately, before she started playing at Ryerson, she was not aware of the potentially serious repercussions. It just takes one concussion to change the course of a life, and having to walk away from hockey, Jakarsezian says, was the worst heartbreak. Right after her athletic career ended, she found herself wanting to ask for help, but felt inhibited by her symptoms.

Ryerson currently follows the U Sports and Ontario University Athletics (OUA) protocol for concussions, which consists of the baseline test that studies an athlete’s response times, according to Dr. Ivan Joseph, director of athletics and women’s varsity soccer coach.

The coach will immediately pull the player if their score is too low, says Joseph. The player will see a therapist when they’re back on campus and sit out of practices and games until they are symptom-free for 24 hours. After that, they begin the Return to Play protocol, which involves a gradual series of exercises over a few days. If the player’s symptoms start up again, they will have to start the process all over again.

All Ryerson athletes have access to the Integrated Services Team. The team has athletic therapists, athletic student therapists, a sports medicine physician, an in-house athletics counsellor and an academic services coordinator.

Adding the sudden end to an athletic career into the equation is what often pushes some people into depression and anxiety

Colleen Amato, a former athlete, understands how important it is for students with concussions to get help. She’s the only in-house counsellor for Ryerson Athletics, so she has to be creative about how to best meet everyone’s needs.

Amato also runs a new injured athlete support group, which had its first session on Jan. 30. The group is a safe space for current and former athletes to talk about their injuries and discuss the prospect of returning to their sport—those with severe injuries may never get back on the field, or the court, or the ice.

In recent years, the scientific and psychological study of concussions has drastically increased. Locally, Ryerson professor Joe Recupero, alongside St. Michael’s Hospital psychiatrists Shree Bhalerao and Ryan Todd, and neurosurgeon Michael Cusimano, created a documentary film about the psychological impact of concussions. This led to a partnership with the National Film Board to create a virtual classroom that discusses sports, concussions and athletes feeling pressured to play through head injuries.

Ryerson’s Jahan Tavakkoli has also collaborated with St. Michael’s researchers. He uses acoustic shock waves to measure the brain’s reaction to a concussion, which can help doctors better understand how to treat brain injuries.

Heather Brown, a second-year history student and former women’s varsity soccer player, says that despite the help she’s received from Ryerson’s athletics staff, there are still too many bureaucratic hoops to jump through when having to prove your mental inability in the classroom.

“There are so many steps to the actual process and so many people you need to meet with. It took more time to do that than go to actual classes,” she says.

Brown has had four diagnosed concussions, but like Jakarsezian, she’s had five additional “off the record” injuries. The first happened when she was just 10 years old, and her first head injury as a Ryerson athlete took place during one of the team’s early games in 2015 when she took an elbow to the head, but continued to play. During that same game, Brown took a second hit. As she slid on the grass to save a shot, a girl from the opposing team fell knee first onto her temple. She immediately blacked out and threw up—two of the most common concussion symptoms. After being taken off the field and put in an ambulance, she had x-rays done to ensure her cheek and temple bones were not fractured.

Coping with the abrupt end of her athletic career was difficult. Post-concussion, Brown found herself struggling with schoolwork. Before the injury, she says she could study for six hours at a time. But doctor’s orders recommended that she study for 10-15 minutes at a time, then take an hour break.

Professors didn’t understand why she couldn’t do her work, or why she wasn’t going to class. Despite her doctor’s advice to take time off of school, her request for academic support had yet to be processed by Ryerson, so she continued to commute an hour from the east-end. One day, she passed out on the subway and woke up at Kipling station—the last stop in the west-end.

Similarly, Jakarsezian describes the university’s accommodation process as “reactive.” “Unless something is brought up in a serious matter, they don’t have a reason to change things.”

The transition wasn’t easy for Brown. She went from being an athlete with a hectic game schedule to a student with too much free time and no distractions.

The slow recovery, accompanied by a long list of medical restrictions, leaves many concussion sufferers living in darkness and isolation for weeks. In extreme cases, it can even last months or years.

Adding the sudden end to an athletic career into the equation is what often pushes some people into depression and anxiety.

“I had to cope with the chapter ending in my life that I wasn’t ready to end. It kinda hits you like a brick,” Brown says. “I was expecting to have another year and all of a sudden, within one week, my career was over.”

When she accepted the fact that she could no longer be on the field, Brown fostered an interest in Olympic weightlifting.

“I had to cope with the chapter ending in my life that I wasn’t ready to end. It kinda hits you like a brick”

Concussion research has seen significant progress over the last six years, but someone like myself—or any of the athletes I spoke with for this story—could have benefitted from more knowledge earlier on. I played rugby for nearly four years throughout high school and sustained four known concussions—two of them put me in the hospital. The rest, I ignored.

My first concussion happened in Grade 9 during my first year on the team. I played a defensive position and made a bad tackle. A girl fell on my face and I blacked out, then vomited on the sideline. One of my last concussions happened during practice. I’m still not sure who hit me. All I really remember was cracking my head against the astroturf on a cold March morning. A string of pain travelled from the bottom of my tailbone to the top of my skull, then everything went black. My dad came and picked me up from the principal’s office and took me to the hospital, where I sat on a chair in the dark and tried to tune out the background noise. I wore a dazed and clueless smile for the rest of my Grade 12 year.

Declan Williams, a former national level judoka, has been practicing judo for more than 10 years and has experienced his fair share of head injuries. He never followed doctor’s recommendations and often refused to go to the hospital so he could continue to compete. But as he got more competitive and the pressure started to mount, his mental health deteriorated.

Williams says he started having aggressive outbursts when he was alone in his room. He remembers breaking down and not wanting to attend his practices. “At the time, I thought this was normal but looking back, you know hindsight is 20/20 and it wasn’t,” he says. Since quitting, Williams says his mental health has improved, despite the occasional dark moment.

As for my own recovery story, I dealt with depression, self harm and an eating disorder after my concussions.

I was educated on what concussions are, but I wasn’t warned about what they can do to you long term, both physically and mentally.

I wasn’t warned about the mornings that I would wake up and wish I hadn’t, or the nights that I would have to resort to something other than an herbal tea or deep breathing to calm me down.

I can say that concussions change the way you see the world. Stories that shine light on those living with brain trauma help destigmatize concussions and start conversations around what can be done better to help those impacted.

Leave a Reply