This summer, the Ontario Progressive Conservatives repealed the updated sex education curriculum. Now, university students reflect on how the curriculum affects them in their adult lives

By Olivia Bednar

When Goldbloom was in high school, they were walking down the hallway to class when a boy reached out and groped their breasts. They were taken aback and felt a familiar feeling of sickness. It was the same feeling they felt every time they were touched without their consent, or got an unwanted slap on their ass, or when a man made a comment about their especially “feminine” body. It was an uncomfortable, alienating feeling—one that caused them to feel like their body was separate from themselves.

Goldbloom, who requested to use only their first name for this piece, hit puberty quite early. Their breasts had developed at age 10, and ever since, they’ve had to endure the unsolicited touches and comments. Some would even try to compliment them for their developed breasts. “Whenever someone said ‘Oh, I wish I had your breasts,’ or something like that, I’m like, ‘No you don’t. It made me a target.’”

They didn’t know what to do to stop the feeling of sickness and the actions that induced it. And on top of that, they couldn’t even fully grasp why it was wrong at all. If Goldbloom had just been told “This is not okay,” they would have understood what sexual assault and rape were at a young age. “I would have been saved a lot of mental health issues, trauma … and suicide attempts,” the fourth-year Ryerson film studies student said.

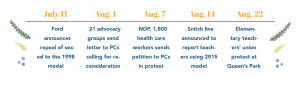

This summer, Ontario Premier Doug Ford, along with the province’s PC party, announced that elementary schools will be required to teach an updated, interim version of the old sex-ed curriculum, which was implemented in 1998 and in effect until 2014. A statement sent to The Eyeopener from the office of the Minister of Education Lisa Thompson read, “Our commitment remains to ensure that Ontario’s children are protected while their parents are respected.” In 2015, a revised version was introduced by the Liberals, which covered many topics the old one did not, like defining consent, LGBTQ+ relationships, gender identities, masturbation and social media’s role in modern sex, including things like sexting and more.

I didn’t have the words to understand that that was not okay.

I will forever be scarred because of that

Students have been taught sex education for three years, between 2015 and 2018. Starting this fall, elementary school teachers must teach the 2018 interim version of the ‘98 model.

With the beginning of the new school year, hundreds of thousands of elementary students will be faced with the regressed sex-ed model. The lack of information on topics like consent and gender identities in the 20-year-old curriculum had a negative impact on the lives of many students that they only recognized much later in adolescence and adulthood. If they had been educated with a better curriculum, they could have avoided identity crises and traumatic events. The Eyeopener spoke to 10 university students in Ontario who were put through the 1998 sex education curriculum in order to explore how it impacted their understanding of pivotal sex-ed related topics.

One of the key things the 2015 curriculum includes that the preceding one does not is the concept of consent, which was introduced to children starting at six years old. The curriculum states: “By the end of Grade 1, students will be able to demonstrate the ability to recognize caring behaviours (e.g., listening with respect, giving positive reinforcement, being helpful) and exploitative behaviours (e.g., inappropriate touching, verbal or physical abuse, bullying), and describe the feelings associated with each.”

By the end of Grade 8, students would be taught the importance of a shared understanding about topics like the reasons for not engaging in sexual activity and the need to communicate clearly with their partners about decisions related to sexual activity.

Goldbloom, however, didn’t have those understandings. They didn’t realize until much later that all the times they were inappropriately touched growing up were in fact instances of sexual assault. “I didn’t have the education or even the words to understand that that was not okay,” Goldbloom said. “And I will forever be scarred because of that.”

According to the Ontario Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services, women know their attacker in three out of four sexual assault incidents. Goldbloom makes up one of the many youths who didn’t realize that sexual violence isn’t just something done by strangers in back alleys. A fourth-year McMaster student told The Eyeopener, “I didn’t know what happened to me was considered rape because it was done by an acquaintance.” They felt so guilty and confused that they told their boyfriend they had cheated on him.

Logan Cerson, a Ryerson film studies graduate, said they didn’t really know about the idea of consent until their second year of university when it was brought up in a conversation. They just thought it was a “physically violent thing where you didn’t know the person.”

“The amount of trauma that was perpetrated on me,” Goldbloom said, “because I didn’t have the language to say ‘stop’ or ‘that’s not okay’ is never going to be fixable.”

In first year, David Jardine was flirting with someone that he met at a pub event on his birthday. After spending some time together, Jardine ended up going back to his place. When they started hooking up, Jardine didn’t think a condom was necessary, but his hookup explained that they needed to use one because STDs were still transferable.

Jardine, now a fourth-year computer science student at Ryerson, assumed it wasn’t needed because he had only been taught in school that they were used in heterosexual relationships to avoid unwanted pregnancies. Jardine was lucky it was pointed out by someone more knowledgeable in safe sex than he was. “I could have very easily caught something from that interaction.”

Jardine found himself turning to the internet in search of what other information he was missing to keep himself safe and informed.

The internet has been a vital tool for many queer people to turn to in order to fill the gaps in their sexual education left by educators in their lives. According to a report by the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network, LGBTQ+ youth were more likely to have searched for health and medical information online compared to non-LGBT youth (81 per cent vs. 46 per cent).

“Google is great if you know what to look for,” Jardine said. But without any prior knowledge on various topics, it becomes difficult to know what to search and what to trust.

If you see yourself in the curriculum,

that means what you are is real

Section C.1.5 of the 2015 curriculum states that “by the end of Grade 8, students will demonstrate an understanding of gender identity (e.g., male, female, two-spirited, transgender, transsexual, intersex), gender expression, and sexual orientation (e.g., heterosexual, gay, lesbian, bisexual), and identify factors that can help individuals of all identities and orientations develop a positive self-concept.” While progress became evident with the 2015 curriculum, it still erroneously listed “male” and “female” as gender identities instead of sexes.

The 1998 curriculum does not mention any relationships or identities other than cisgender heterosexual ones. The word “gender” comes up only once, in the phrase “gender roles.” This excludes several identities and orientations, which, if included, could have validated what many students were going through.

“If you see yourself in the curriculum,” Jardine said, “and your teacher is teaching you about something that you are, that means what you are is real.”

The Eye spoke to a Grade 8 teacher at a Catholic school in Mississauga, who requested to remain anonymous in this story. She said that she will still find her own way to implement important concepts in her teachings, in spite of the potential consequences from the provincial government. She plans to teach her students about modern topics like sexting and consent. “I will use that language, I think it’s incredibly important, especially for the older kids. It’s dangerous not to teach them these things.”

She plans to teach what is outlined in the curriculum in place but will hold a question and answer period to answer any questions students still have. “I am offended that the minister is even calling it the 2014 curriculum,” she says. “It’s a curriculum that was designed 20 years ago.”

The Ford government announced that parents would be able to report teachers to the government if they find that their child is being taught the repealed curriculum.

Whether or not this will result in consequences for the teachers remains unclear, as the elementary teachers union has gone forward with a court challenge against the “snitch line” calling it an “abuse of power.”

Winnie Wang always had a small chest. It was the root of the bullying they experienced growing up. Peers would make fun of them for this, but Wang oddly felt complimented by what was intended to be an insult.

“Why aren’t I offended by this?” they would ask their friends, who would never know how to respond. Wang didn’t realize it at the time, but it was because they wanted to present as less femme.

The fourth-year University of Toronto student, who studies neuroscience and cinema, said that in their first year, they discovered what non-binary gender was, while they were simply scrolling through Twitter one day. “I was finally like, ‘This makes sense, why didn’t I know about this.’”

Wang felt disconnected during their sex education classes in elementary and high school. They were taught that a woman is someone with a vagina, but Wang didn’t relate. “I felt so distracted, confused, alienated, the whole time.” Wang added they didn’t even know about the existence of transgender people until Grade 10, from searches on the internet. But they still thought there were only trans men or trans women. For some time, they thought they might be a trans man until they discovered gender identity as a spectrum and came to identify as non-binary.

Wang then came out to their younger brother, who had been taught the newer curriculum. When they told their brother, he already knew about trans identities and what it meant to be non-binary, and was completely accepting of it.

“It was really crazy to me that my brother already knew these things that I had to learn on Tumblr or just the internet in general,” Wang said. “I feel like I would have just been okay with myself growing up [having been taught the new curriculum] … I would have just been like, ‘Oh, I feel this way because I am non-binary.’”

In middle school, Goldbloom started to develop feelings for one of their friends. But one day, she told Goldbloom that they were being too clingy. Goldbloom recalls it hurt “so bad.”

“I didn’t know why I felt what I felt and I didn’t have words for why I felt what I felt,” Goldbloom said. “And I think it escalated from there because I kind of assumed being gay was a negative thing. A sin. It wasn’t something you could be or were even allowed to be.”

While some teachers are combatting what’s ahead for elementary students, Goldbloom added it’s not enough to just teach kids to understand these concepts. “These queer kids are at such a risk of being kicked out of their homes, rejected by their families, of literally being homeless, murdered, not feeling safe in their own surroundings,” Goldbloom said.

From middle school to today, Goldbloom still struggles with being a pansexual non-binary person. “If I had had that education at an earlier age, then I wouldn’t be going through this.”

Leave a Reply