By Shaki Sutharsan

CONTENT WARNING: This article contains mentions of violence and suicide.

Iranian women at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) are standing in solidarity with those in Iran as protests continue.

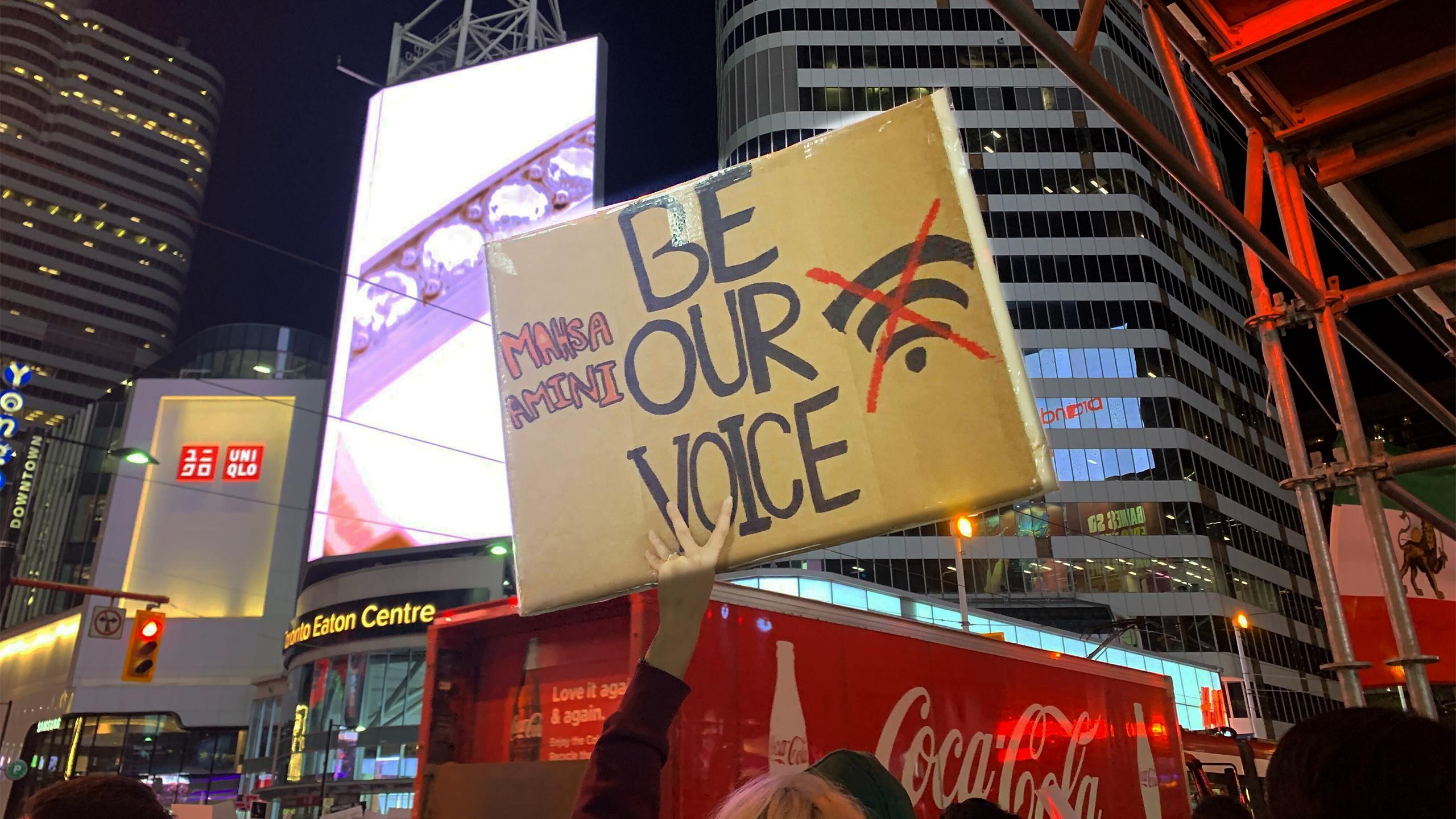

Many Iranian students have been organizing protests at Yonge-Dundas Square over the last several weeks. Among the organizers is third-year engineering student, Hijrah Nasser*. She said the goal has been to gather the support of students and other young people in Toronto.

“I really wanted to shed light on the fact that these children of the [Iranian] immigrants are also very passionate about what’s going on,” said Nasser.

“This is a very compromising protest”

She explained that both her parents immigrated from Iran, relaying stories about the country’s laws, saying she was familiar with hearing about tragedies like Mahsa Amini’s.

In September, 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died in hospital, days after being detained by Iran’s morality police for allegedly not having her hair adequately covered, according to CBC News. Hossein Rahimi, Tehran’s chief of police, said Amini’s death was an “unfortunate” incident, denying witness accusations that officers had beat her.

Protests have erupted across Iran in the weeks following her death, with women demonstrating against the country’s dress code laws by burning their headscarves and cutting their hair. In Toronto this weekend, a human chain formed from Yonge Street to Steeles Avenue. Similar human chain protests occurred in areas across Canada, including Vancouver, Winnipeg, Calgary, Edmonton, Ottawa and St. John’s.

“We hear about this situation every so often”

Third-year professional communications student, Rojhin Taebi, said she was saddened by Amini’s death and was reminded of her cousins living in Tehran, who are the same age as Amini.

But she said she wasn’t shocked by the news. “We hear about this situation every so often,” Taebi said.

This kind of arrest is not uncommon in Iran. In 2019, 29-year-old Sahar Khodayari dressed as a man to attend a soccer game in Iran and was arrested. She allegedly died by suicide after learning she could spend up to six months in prison.

Women have been required by law to cover their hair, arms and legs in public since the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979 but the severity of the enforcement of dress code laws has varied depending on who is in power.

Nima Naghibi, an English professor at TMU and an Iranian scholar, said the morality police are tasked by the President of Iran with enforcing the modesty dress code. While this also affects men, the rules are more strict for women. She explained that the current president, Ebrahim Raisi, imposed tighter restrictions and gave the morality police more power than previous leaders.

“Usually you just hear she was pushed around or they took her in a car or they ripped her whole hijab off and started hurting this young woman,” Taebi said. “But this was a more very extreme approach.”

The Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada said in a 2020 report that the nature of enforcement in Iran varies based on the location and time period of the alleged dress code violation. According to the report, a woman accused of “bad hijab,” or inadequately covering themselves according to the law might be escorted to a police station until a family member comes to provide them with clothing that’s considered adequate.

“Women’s issues are now placed at the forefront of these protests”

Others might be made to attend classes provided by police. However, there are also accounts of women alleging they were brutalized by police after being accused of violating dress code laws.

Taebi added that recent protests feel different from others that have happened in Iran in the past. The last time protests of a similar calibre occurred was in 2019, when protestors demonstrated against the increasing state-controlled price of gasoline. This time, women are taking the lead.

“This is a very compromising protest in that the women are front and centre,” Taebi said.

Rahmah Asghar*, a representative for the Iranian Students’ Association of TMU, said she has been checking social media and the news frequently to stay informed of events, though she added that it has been difficult to do so with the widespread internet outages in Iran since the protests began.

“I’m hopeful and exactly at the [same] time, I’m hopeless as well because so many people are dying,” said Asghar. “They’re killed on the streets.”

“What they’re asking for is freedom of choice”

Naghibi, who originally immigrated to Canada from Iran when she was 12, has written about Iranian feminist movements. Naghibi echoed Taebi in saying these protests feel different from ones that have taken place in Iran throughout the 20th century.

“What’s interesting about this particular moment—and the slogan; woman, life, freedom—is that women’s issues are now placed at the forefront of these protests. And they are refusing to take a back seat,” Naghibi said. “They’re refusing to let their movement get co-opted.”

Naghibi has been published academically for her text, “Rethinking Global Sisterhood: Western Feminism And Iran,” drawing initial criticisms from how the western world handled Iran’s 1979 political revolution, when the hijab became mandatory. Muslim feminists from around the world have been vocal in stating that the choice to wear the hijab is deeply personal. Naghibi also pointed out that the core issue is women’s choice, not religion.

“It’s not an anti-hijab protest,” Naghibi said. “What they’re asking for is freedom of choice—the decision to wear the veil or not wear the veil.”

She noted that the protests in Iran have seemingly paused the morality police. “It shows that the government is becoming a little bit scared,” Naghibi said.

*Names have been changed to protect sources’ privacy and security

Leave a Reply