By Jonah Brunet

Randy Boyagoda can’t remember what he said to the Pope. He’s pretty sure he mentioned Ryerson but beyond that – pure gibberish.

He stepped off the bus in Vatican City last September onto the cobblestones of a sunny courtyard.

His group, a team of media experts and scholars fresh from the church’s bi-annual conference on social communications, passed through a series of hallways. Everything was beautiful, flecked with gold. The building itself was a work of art, a constant reminder of the venue’s historic and spiritual grandeur. They waited in a meeting room where serene Renaissance-era frescoes tugged their eyes to the ceiling. After 15 minutes, Pope Francis arrived.

He gave a speech in Italian, of which Boyagoda understood little.

“The problem that the Vatican has isn’t that it doesn’t know what to do with social media. It’s that it does too much. There’s just tons of things out there, and so it’s overwhelming if you try and engage with it.” – Randy Boyagoda

Francis seemed jovial, cracked a few jokes, smiled and strayed from his script. Then each guest was given 15 seconds to say something to the face of Catholicism in the modern world.

“Honestly, I mean I’m an English professor, I’m a novelist, I think to myself I can speak quite well,” says Boyagoda, director of zone learning at Ryerson’s Digital Media Zone.

“But in the intensity of the moment, you kind of lose your ability.” One year later, a group of Ryerson students are coaching the Vatican on improving their use of social media. In June, they met with Monsignor Paul Tighe, secretary of the Pontifical Council for Social Communications (PCSC), to present ways in which the church could better harness tools like Twitter and mobile apps. This fall, the council continues reaching out to Ryerson with Skype meetings and plans for continued student input.

Whatever Boyagoda said, it seems to have worked. In an age when you’re three times more likely to get a computer virus from a religious website than a porn site, a study by Symantec in 2011 found, it’s clear that being digitally savvy isn’t in the skill set of the average church leader. The Vatican is no exception. Though the willingness to connect is strong, a meagre understanding of social media platforms within the walls of Vatican City weakens their ability to maintain a strong online presence.

“The problem that the Vatican has isn’t that it doesn’t know what to do with social media,” Boyagoda says. “It’s that it does too much. There’s just tons of things out there, and so it’s overwhelming if you try and engage with it.”

What the church needs is a more finessed approach, aware of the subtleties and inner-workings of the most popular platforms among today’s youth. The Catholic Church represents the oldest branch of Christianity and sees social media as a chance to reconnect with a young population that has become disenchanted with the religion.

And, in Ryerson students, they see a way to make that happen.

It may not be the most likely of partnerships. Ryerson isn’t the largest university in Toronto, let alone the entire world – which is, after all, the pool an organization as vast and influential as the Catholic Church can fish when it needs a favour. What we do have, however, are two things the 2,000-year-old church needs – expertise in social media and the aparatus to put it to use.

“What they wanted were ideas and suggestions from end-users,” Boyagoda says. “Young people who are digitally savvy and serious about their faith.”

The partnership started over coffee between Ryerson President Sheldon Levy and Thomas Collins, archbishop of Toronto. When the two met in last August, Levy, too ambitious and business-minded for a simple meet-and-greet, was eager for something on which the two institutional leaders could collaborate.

Collins mentioned the council’s September conference, prompting Levy to send Boyagoda as a formal observer, tasked with finding a role for Ryerson in the church’s ongoing push for more connectivity.

The office at the Vatican responsible for their online presence is the PCSC. Established in 1948, it originally focused on cinema, seeking to spread the message of the gospel through new filmmaking technology.

“Even though the church is very hierarchical, this was a completely open meeting. All the cardinals and bishops there were saying, ‘We don’t know, and we know we don’t know, so tell us what you think.’” -Randy Boyagoda

The PCSC has also dabbled in radio and television. Now however, the focus is squarely on digital and social media – new tools that offer the same, if not more, communicative power as the old ones, along with new opportunities for global two-way communication between the church and its followers.

“The church isn’t meant just to be a megaphone that shouts down at the world from above,” says Brandon Vogt, author of The Church and New Media. “It’s meant to be in conversation with the world, much like Jesus was … That’s what these tools allow us to do.”

For Boyagoda, the old megaphone church had disappeared.

The PCSC conference, held in Rome last September, took place outside the Swiss-guarded walls of Vatican City in a modest twostorey meeting hall on the Villa di Conciliazione – the road leading up to St. Peter’s Basilica. The cardinals and bishops had traded their formal gowns for jackets, with only roman collars and simple pectoral crosses to denote their religious authority. Each speaker echoed in simultaneous translation to audience headsets, accommodating the six different language groups represented from around the world.

“Even though the church is very hierarchical, this was a completely open meeting,” Boyagoda says. “All the cardinals and bishops there were saying, ‘We don’t know, and we know we don’t know, so tell us what you think.'”

Then came Collins’ speech. In what Boyagoda calls the key moment of the conference, the archbishop took the stage and said the church should be looking to a place like Ryerson University, where they have students on the cutting edge of digital media in the 21st century – a glorious name-drop from a well-respected church official to a powerful audience, and one that caused Tighe to seek out Boyagoda afterwards and ultimately strike up the university’s ongoing partnership with the Catholic Church. The Ryerson team, assembled by Boyagoda with the help of Oriana Bertucci, Ryerson’s director of chaplaincy, was culled from the Catholic Students’ Association. It comprised two students and one alumnus: Melissa Siu-Chong, Sandra Mucyo and RTA graduate Augustine Dimagiba.

Siu-Chong, 20, a hospitality student and former vice president of communications for the Catholic Students’ Association, was an obvious choice. As was Dimagiba, graduate of a program with a strong focus on digital media. Less obvious was Mucyo, 21, a chemical engineering student who says she didn’t have any specific prior experience with social media going into the project. But simply being a young student in Toronto was qualification enough, she says.

“In North America the culture’s very open to new social media, and we easily embrace and adapt to it,” Mucyo says. “You have that everyday experience that somebody from the Vatican or a different generation doesn’t necessarily have … They’re people who are sheltered from this kind of stuff.”

Beginning in the fall of last year, the team met monthly to delegate topics, share their findings and refine their ideas. A main focus was the Pope App, a mobile app that curates the PCSC’s many different online endeavours and provides live updates on the pope’s schedule, who he’s meeting and what he’s said. Once perfected, the idea is for The Pope App to form a missing link, solving Boyagoda’s main problem with Vatican media by tying together each scattered online resource for an ultimately more engaging, user-friendly experience.

The app was already available when Ryerson’s team started work, but they’ve been working on improving it.

By June, after a dozen meetings and nearly a year of preparation, Tighe had arrived. Both Mucyo and Siu-Chong confess feeling nervous going into the meeting, but their anxiety was soon erased. While he could have easily seemed out of place in the Digital Media Zone, an ultra-modern media enclave with its name boldly spray-painted in blue on an orange ceiling, Tighe seemed at home, energetic, ecstatic to be meeting Toronto’s young students where they thrived: at the epicentre of Ryerson’s digital world. He listened intently, gestured emphatically and spoke encouragingly in his lively Irish accent. At one point, he found himself overwhelmed by the students’ many suggestions.

“He had a really interesting reaction,” Boyagoda says of Tighe.

“His first response was, ‘This is impossible, there’s no way any of this could be done.’ And then his second response was, ‘But that’s not the right reaction. How do we make this possible? How do we try to get this done?'”

After the presentation, he joined the students for brunch and later strolled with them through Ryerson’s campus. He laughed often and, according to Siu-Chong, was always smiling. Tighe represented a different Catholic Church than history had known – one aware of its shortcomings and open to suggestion. Even for young North American students, constantly immersed in a technological culture where social media is ubiquitous and unavoidable, some questions had no easy answer. The possibilities offered by a digital capacity for two-way communication also come with a host of problems from an online world that is not entirely friendly toward the church.

“If you look at any of Pope Francis’ tweets,” says Vogt, “you’ll see that they’re filled with vulgar responses, negative reactions, people – many of them atheists – posting very negative things.”

It’s a general rule on the internet that nothing is sacred, no comment or post safe from vicious attack. The church’s challenge is operating in an online environment that so pointedly refuses to recognize religious authority.

“You’re able to thrust your voice into a much larger conversation. One in which before, maybe 10 or 20 years ago, you wouldn’t have been invited. I think the opportunity far outweighs the challenges.” -Brandon Vogt

“The interesting question is what does it mean for a hierarchical institution like the Catholic Church to be involved in a very horizontal plane?” Boyagoda says.

This problem is most obvious in the case of Facebook. The main reason Pope Francis doesn’t have a Facebook profile is due to the seemingly unavoidable spew of offensive posts it would invite from an online community that loves a chance to stick it to the man.

Siu-Chong, Mucyo and Dimagiba were undecided on whether the pope should be on Facebook, the largest social media network in the world, but the project is far from over.

For Vogt, however, the Vatican’s fears are misguided. “You’re able to thrust your voice into a much larger conversation,” he says.

“One in which before, maybe 10 or 20 years ago, you wouldn’t have been invited. I think the opportunity far outweighs the challenges.”

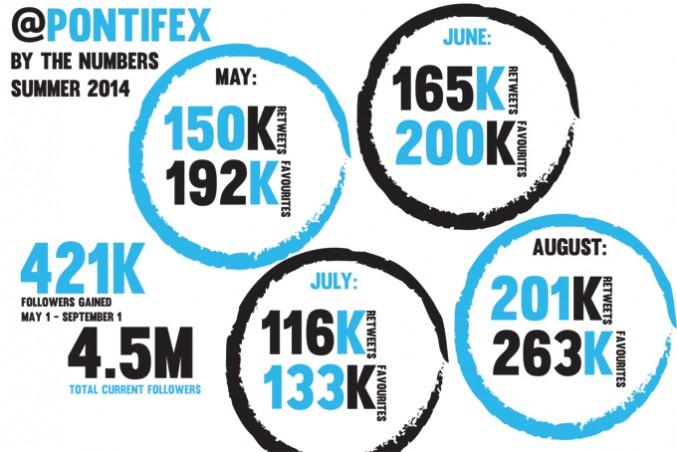

Pope Francis isn’t the type to prefer sheltered security over the chance to connect with his followers either. Siu-Chong recalls hearing many stories of him simply going out and walking around Rome, despite being warned against it by concerned officials. He was the most mentioned name on Facebook last year, according to Vogt, and his tweets are retweeted more on average than any other world leader’s.

Shortly after being appointed, he appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine. His outspoken concern for the poor has earned him plenty of respect, even from secular individuals. More than any before him, Pope Francis is a celebrity and the ideal person to further the church’s social media presence. But Siu-Chong approaches the pope’s popularity with caution.

“I think it’s good and bad at the same time,” she says. “It’s good because it’s subliminally passing on the evangelization message that yeah, our pope is cool. But he has a purpose. He’s not just a celebrity.”

After the June meeting, Tighe said he was eager to extend the media partnership into the coming years. Upon Tighe’s return to Rome, the Pope announced a new commission to re-examine the Vatican’s media presence. On Sept. 18, a Skype meeting was held with a PCSC representative working under Tighe, who sought student feedback on recent upgrades to the Pope App.

On the Ryerson end, the group plans to become a more formal student entity. Ryerson is starting up a third media zone, along with the Digital Media and Transmedia zones, according to Bertucci. This new development, called the Social Communications Zone, would be a perfect fit for the group, she says.

The student group is also looking to expand its membership by opening the doors to non-Catholic students as well, Bertucci says.

“The desire is to bring other students who might just have an interest in faith in general or religion in the social world,” she says. “I think those voices need to be heard.”

When Boyagoda returned to Ryerson from Rome, he brought a gift for Levy – a book of tweets. The ornate, bound, Vatican library edition tome juxtaposed gorgeous Roman artwork alongside printed screenshots of the pope’s Twitter activity. It joins the Vatican library’s collection of the most sacred and important religious texts from the past two millennia.

For Boyagoda, the book was a symbol of the help the Church needs when it comes to digital media.

“There’s a very genuine sense that when the pope speaks, this is something that should be captured for all eternity,” he says. “It really did suggest how much in need the Vatican was of a young-person’s view of how social media works … and how Ryerson students could help it reimagine its social media future.”

This is the challenge facing the group of Ryerson students – a church that confuses the permanence of religious doctrine with the fleeting existence of tweets. There’s a sense that the Church is digitally backwards, stuck in the past.

However, drawing from the fresh ideas of Ryerson’s technologically immersed youth, Tighe and the Vatican aim to break down that stereotype. The notion of the clumsy, bumbling Catholic media decorating a book of tweets may have nearly run its course.

Leave a Reply