By Vanessa Thomas

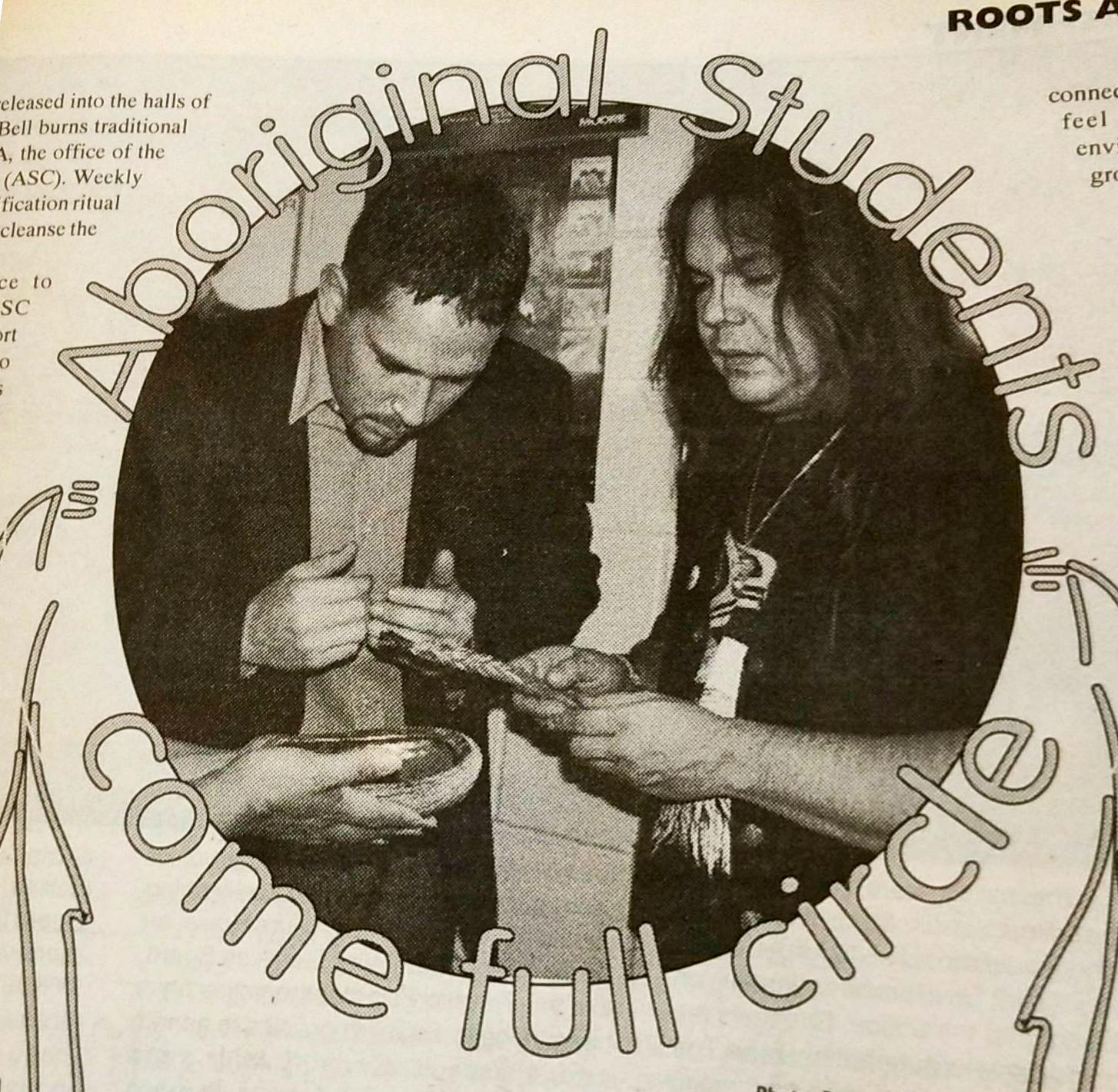

A musky scent is released into the halls of Jorgenson Hall as Mark Bell burns traditional sweet grass in room 345A, the office of the Aboriginal Student Circle (ASC). Weekly meetings are home to a purification ritual called smudging, meant to cleanse the mind, body and spirit.

Besides being a place to perform smudging, ASC meetings act as a peer support system for its members who are trying to mend their wounds of abuse, isolation and assimilation — all products of being native in a non-native society.

Established last year, the ASC acts as an extended family to members, addressing current affairs and tackling personal issues.

Bell, and Ojibwa aboriginal and co-facilitator for the ASC, says he has learned a lot about himself through the ASC. Living on the Wikwemikong reserve of Manatoulin Island, his abuse began when he was 10 years old. He says he grew up in “a dysfunctional family” where he suffered constant verbal abuse from his white step-father. Bell turned to drugs and alcohol to console his sadness.

“I was living a life of self-destruction. It was only when I began to speak about my abuse that I started to help those feelings — the pain, the anger, the sadness. I will be healing for the rest of my life,” he says.

Three years ago, Bell decided to leave the reserve in pursuit of a new life. At 33, Bell is a recovered addict and an early childhood education student at Ryerson.

“The people [in the ASC] are real with real emotions. I’ve faced my difficulties in the group and so have others. There is a trust [among the ASC] that makes me so excited, it brings me peace.”

Talking circles, where members sit in a circle and solve problems as a group, are a traditional way of addressing issues in the Native community. Bell finds the healing process easier in this type of forum.

“I’m accepted in talking circles because no harsh judgements are made,” says Bell.

Many aboriginals who go to Ryerson come from outside Toronto and for those who are already part of the ASC, dealing with their feelings of isolation in a different culture is a recurring theme. Warren Stanley is a Plains Cree aboriginal and treasurer of the ASC. He says he felt pressure to assimilate after moving to Toronto last year from his small, close-knit community on a reserve in North Battleford, Sask.

“I lived in a community that basically had two cultures, whites and natives. All my friends were native. I went from a reserve where everyone know you and you know everyone, to Ryerson, where I knew no one,” says Stanley, a social work student. “Here it was different. It’s a pool of everyone. I felt lost, like there was nowhere I could connect. The group [ASC] helped me to feel comfortable in my new environment. The majority of the group are my friends.”

In order to exist as a student group, the ASC has decided to conform somewhat to mainstream western customs. Aboriginal culture avoids hierarchies, but the ASC has a facilitator, two treasurers, co-facilitator and the rest of its members. Out of the estimated 60 aboriginal students at Ryerson, only 11 are members of the ASC. Their main goal this year is to attract more members. The largest event planned for the year is the Aboriginal Awareness Day in March. Stanley remembers the eye-opening experience he had at the awareness day last year.

“This white girl asked me, ‘where’s your long hair?’ as if all natives have long hair,” recalls Stanley. “Some people think we’re out on the reserve living in teepees, still wearing loin clothing and chasing buffaloes out on the plain. We’re not feather-wearing, scalp-taking people, we’re here at Ryerson getting out education. We’re also in positions of power but these stereotypes are perpetuated on TV.”

As a student advisor at the Aboriginal Student Services, Anthony Ristine is one aboriginal who holds a position of power at Ryerson and doesn’t appreciate these stereotypes either. Ristine has a law degree from the University of Western Ontario and a master’s degree in social work from the University of Toronto. He provides academic and personal advising for aboriginal students at Ryerson.

“The facilitator [Bell] is my link to the students. Most aboriginals are not used to institutional services, so students may not come to me directly,” Ristine says.

“The facilitator works with me to get students to talk. The student goes to the facilitator with the problem and the facilitator comes to me. If I need more expertise I can refer them to Native healing outside of Ryerson.”

Ristine, a 31-year-old Onyota’a:ka Nations aboriginal, is a self-proclaimed “white-looking aboriginal.” He was put up for adoption at age two, and raised by a non-native family in London, Ont.

“I could have gone either way — native or white — but I always knew I was aboriginal,” says Ristine. “I received a non-native education, but I was lucky to have understanding parents who made me knowledgeable about my aboriginal history.” Ristine attributes his success to a nurturing and loving family life he had growing up. “I was lucky that I had the support. Not all aboriginals have the support, that’s why we need services like this to provide cultural support in an educational setting.”

Leave a Reply