By Xavine Bryan

The noisy blur of dance music and the gossip of other clients mingled to make an unlikely soundtrack to my thoughts. I didn’t realize it at the time, sitting in my hairdresser’s chair five years ago, but I was contemplating the near impossible. After years of straightening my hair, I decided I wanted to totally abandon chemical relaxers and let my hair grow “natural.”

Going natural meant I would wear my hair in its naturally “kinky” state. (The best example of a natural hairstyle is an afro, but there are many others). Everyone thought I was crazy and no one hesitated to tell me so.

When my hairdresser started parting my hair into sections to place the strong-smelling, corrosive chemicals onto my new-growth, I told her about my decision.

“Are you crazy?” She looked startled. “You can’t grow your natural hair. It’s going to grow back even more nappy,” she said referring to the tight lateral curls common to black hair. By the tone of her voice I could tell she thought I was forfeiting any claim to a normal life. Not many 16-year-old black girls would be willing to let their hair grow without chemical intervention. Nobody wanted “naps.”

I tried to explain to the hairdresser I was tired of hair breakage due to constant perming — I’d been doing it every three months since I was 13. While my chemically treated, shoulder-length hair was as straight as it could be, it was all falling out.

The hairdresser then looked at my mother, who just shrugged disapprovingly.

“I already told her,” she said. “It’s her hair. If she wants to walk around looking like that, that’s her business.”

So instead of relaxing my hair, the hairdresser washed it, combed it back, and said she would see me soon after I gave up trying to grow my hair natural.

She was right. I quickly gave up and was back to straightening my hair in a few months. Looking back, I can see why I failed the first time I made this decision. For most black women, the only thing harder than accepting what God put on our heads is getting everyone else around to do the same.

My mother and the hairdresser were not the only ones who didn’t understand what I wanted to do — all my black friends had their own hair-straightening obsessions, fleeing to the hairdresser’s at the mere sight of new growth. My boyfriend, at the time, told me he would break up with me, fearing my hair wouldn’t look good.

As with most black women, my odyssey with hair started early in life. I had always loved my long thick curly hair but there came a point when my school mates pointed out my hair was different. It happened when I was walking to school from swimming lessons. Some kids were commenting on the fact that my hair after being in the chlorinated water for hours, had become puffy and dry. I looked a bit like a human chia pet.

Being in grade five, I wasn’t too interested in boys yet, so it didn’t really bug me until someone shouted from behind me, “Hey, Medusa, where you going with that big hair?”

I turned around to face the boy who was walking quickly towards me. “Your hair looks like a pile of snakes,” he said.

Then everyone started laughing. Everyone except me.

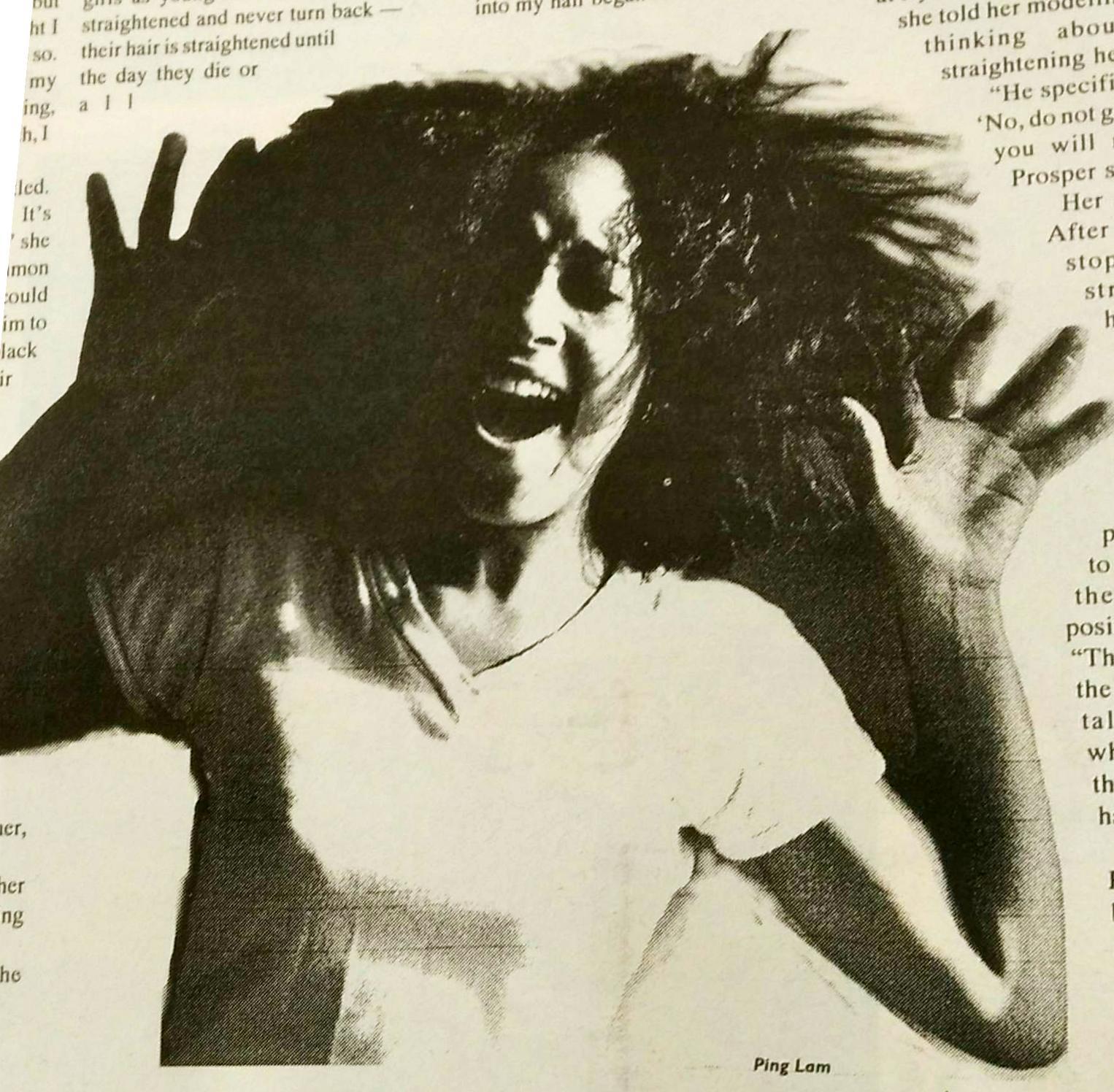

There are many derogatory names for black hair, most of them we use on ourselves — naps, nigger-knots, pepper corns. While many white or Asian girls may choose to perm their hair to make it curly for a change of pace, some black girls as young as five have their hair straightened and never turn back — their hair is straightened until the day they die or all their hair falls out.

By grade seve, I had enough of being different and I asked my mother if I could put a relaxer in my hair. After all, the black women I saw in magazines, even my own mother, had straight, shiny hair and I wanted it too.

I had mixed feelings, as the chemicals were spread liberally with a plastic spatula through my “virgin” hair (it’s too dangerous to touch with your hands). On one hand, I was grateful to be getting rid of the “big” hair everyone was always teasing me about. On the other hand, I felt I was losing a part of what made me unique.

When it was over, three hours later, I looked at myself in the mirror and shook my long, shiny black hair. I finally had hair that looked like the women I saw on television, in magazines and on billboards.

For a while I was pleased with myself. None of the boys teased me anymore and fewer people asked me why my hair was “weird-looking.”

However, it didn’t last. By 16, the effect of putting chemicals constantly into my hair began to take its toll.

First my hair split and broke at the ends, then at the roots. My hair no longer flowed down my back. It looked like a blind man took scissors to my hair while I was sleeping. This was definitely not the look I wanted.

The reasons black women submit to these agonizing beauty rituals is not simple. Every day, we’re bombarded with images of what is beautiful. If white women complain of the debilitating expectations of media-constructed beauty standards, imagine what’s going on in the heads of young black girls with cornrows and thick braids. The black actresses or news anchors we see on TV all have straightened hair or weaves (store-bought hair). Is it any wonder why black girls want to give up what they have in a heartbeat?

For some women who decide to go natural, talking to others who are going through the same thing makes up for the lack of support we get socially.

Ivy Prosper, a former model and graduate of the fashion design program at Ryerson, vividly remembers that day she told her modelling agent she was thinking about no longer straightening her hair.

“He specifically said to me, ‘No, do not go natural because you will not get work,’” Prosper says.

Heer agent was right. After she decided to stop chemically straightening her hair, she got fewer calls for modelling assignments. “I’ve spoken to people on the phone before I go to an interview and they sound really positive,” she explains. “Then when I get to the interview and they talk with me, the whole time I can see their eyes are on my hair.”

Unfortunately, Prosper doesn’t believe the negative image of black hair will change any time soon. She remembers one boyfriend who offered to pay for her to continue straightening her hair.

“Black women have to feel good about being themselves and black men have to feel good about us being ourselves,” says Prosper.

“I couldn’t be bothered with the hassle of going to the hairdresser every few months. [Besides], I was looking at older black women and noticed that a lot of their hair was thinning,” she says. “Many of them said it was because of years and years of relaxing their hair.”

But she admits going natural was a difficult transition to make. She realized she had forgotten how to comb and style her naturally curly hair.

“Now I’ve gotten used to it,” says Prosper, “and I have no problems with it. I wouldn’t relax it again.”

Now, I’m 21-years-old and like Prosper, I’ve also decided never to relax my hair again. With more and more young women like myself doing the same, it’s been much easier this time around. I know I can stick it out.

Leave a Reply