By Katharine Sealey

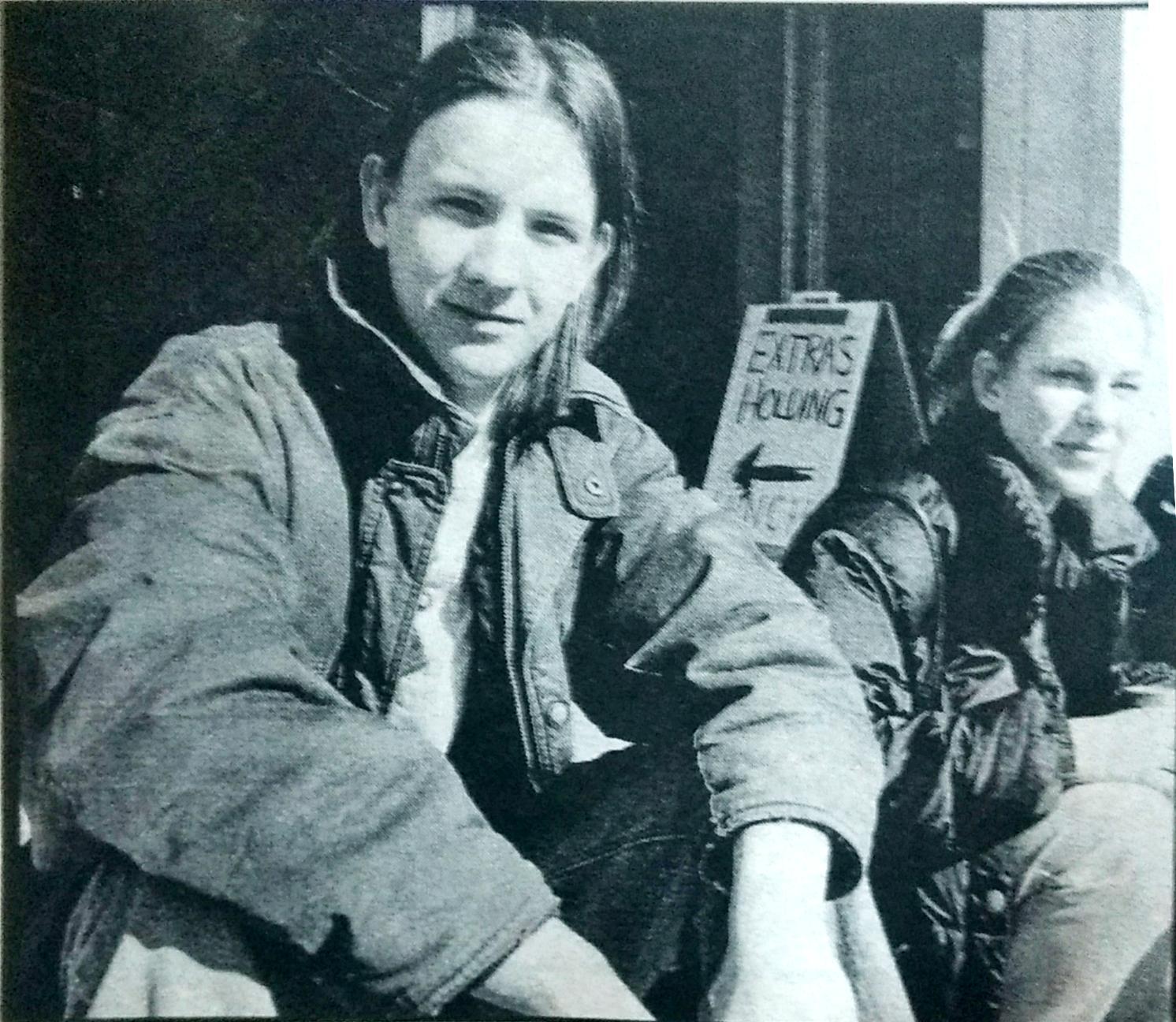

If you need a job, drop the classified ads and pick up the entertainment section instead. Toronto is a hotspot for Hollywood filming and all those productions need extras, especially young ones. “People my age are always needed, because we can look younger or older and we tend to have more flexible schedules,” says Siobhan McLaughlin, 22, of Mississauga. “The money for extras is really good. I spent only five days on the set of the Kids in the Hall movie and I made over $900. It’s not hard to get the work because there is always something filming.”

Toronto is currently ranked as the third most popular filming location, behind only Los Angeles and New York. In March — usually a slow production month — there were 18 crews at work, including six-hour mini-series, four TV movies, five features, several weekly series and two pilots.

Extras are those “extra” people in a scene who aren’t affecting the action — a person walking a dog in the park, cops milling around a police station or a mob of teenagers at a rock concert. “If the extras are doing their job properly, you won’t even notice them,” says casting director Jane Rogers, who has cast for Due South, Goosebumps and the feature film Extreme Measures. “But extras are vital to the production because they set the scene.”

She says there’s nothing particularly tricky about being an extra. “Anyone with half a brain can do it. All you have to do is stand where they tell you to, and move when they yell action. It’s not brain surgery.”

“It hardly seems like work at all,” says Silver Chosla, 21, a fourth-year business management student at Ryerson. A few weeks ago, he began work as an “Asian junkie” on his first film, The Corrupter, with action star Chow Yun-Fat and Mark Wahlberg. “There’s lots of down time, but they feed us a lot,” he says. “We just wait to be told what to do.”

Cheryl Gallant, the head booking agent for the Manhattan Agency in Mississauga, says the job does take a bit of intellect. “You need to be smart, so you’re directable and dependable and you have to have a pleasant personality,” says Gallant. “Directors don’t like people who just talk, talk, talk. Those people tend to get banned from sets.”

The pay for extras ranges from $7 for $17.50 an hour but Gallant and Rogers both suggest the first thing a hopeful extra should do is find a good agent. “Anybody off the street could go and [be an extra] but, nine times out of 10, a production company will call an agency to find their extras,” says Gallant.

Gallant recommends checking with ACTRA (Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists) before signing with an agent. “ACTRA will give you a list of reputable agencies,” she says. “Some are a scam, so it’s best to see the place and ask a lot of questions. If you don’t like the atmosphere or the answers, don’t sign.”

Rogers says one of the best indications of a sca, is a large sign up fee. “Paying $200 to get on a list: that’s totally insane.” She says $50 is more realistic. Also beware of companies offering extra courses. “You don’t need a course to be an extra. If you can chew gum and walk at the same time, you can be an extra.”

Gallant says legitimate companies may ask potential extras to fill out questionnaires. “We need to know your statistics, what type of car you drive, if you have pets, if you have anything special in your wardrobe, your hobbies and special skills. It sounds strange, but you never know when a casting director might ask,” she says. “I once had a request for a 14-year-old blond girl who could drive an ATV — and I actually found one, using the questionnaire.”

“There are some people I call ‘professional extras,’” says Rogers. “They can ballroom dance, ride a horse, roller skate, they own their own tuxedos — they can switch on and off and I can rely on them. Some take it really seriously. They carry pagers so I can reach the, any time.”

Dave Milne, 20, of Mississauga, doesn’t think he wants to be a professional. He found his work extra frustrating. “I was up for a part in Exotica,” he explains. “I went for the interview, and they wanted me to pay $75 for photos and I had to bring changes of clothes and the set was on the total other side of town and I didn’t have a ride there or back. It was just such a hassle.” Despite past problems, Milne says he would try again if another opportunity arose. “My friend Shaun was in the background of a fight scene (for Johnny Mcnemonic),” says Milne. “He was only there for two and a half days but he made $600 and met Ice-T, so it’s good work if you have the time. It sure beats flipping burgers or answering phones.”

“The money is nice, but you can’t really live off it,” agrees Chosla. “I did it just to meet Chow Yun-Fat. I don’t really know if I would do it again. It would depend on what it was.”

McLaughlin says an extra needs to decide how committed they are and where they are going to draw the line. “Sometimes they want you to change things about yourself,” she says. “I auditioned for a role in Midnight Train, and they told me I would have to cut off all my hair and then dye it. It took a long time to grow my hair to where it is now,” she said, pointing to the middle of her back. “So I decided it wasn’t worth it for a few seconds on the screen.”

Extras should also be prepared for ever-shifting schedules, warns McLaughlin. “One of the biggest problems is odd hours. When I was working on Kids, I got a call at 6:30 a.m. to work until 1 a.m. the next day. When they call, you just drop everything and go.”

Aside from the opportunity to see yourself on TV or in a movie, McLaughlin says a major benefit of being an extra is the opportunity to meet celebrities. “I got to meet Ricki Lake and Brendan Fraser on Mrs. Winterbourne and I met all of the Kids in the Hall,” she says, but adds a warning. “That was just luck, you can’t expect to meet the stars. You have to remember that being an extra is a job; you’re not there to socialize.”

“The actors are there to work and so are you,” says Rogers. “It’s not professional to bother them or hold up a production to get an autograph.”

McLaughlin says the real satisfaction comes months — sometimes years — later, when the piece is ready. “When you’re on the set, you think, ‘this is so stupid’” she says. “But then you see it on TV or on the big screen and then it’s ‘Oh, that’s what we were doing!’ And once you’ve done it you can’t help but notice all the people in the background and you really appreciate how hard it is to look like you’re not doing anything.”

Leave a Reply