By Ryan Silverman

It’s a miserable October day outside Rob Valentini’s fifth-storey apartment. The streets are dark and wet, and the relentless winds scatter soggy newspapers on the ground.

Thick columns of traffic make their way up the streets of his midtown Toronto neighbourhood. The view from Valentini’s window is of the local Blockbuster Videostore’s bright neon sign; inside the store, business is bustling.

Valentini has never liked rainy days. At times like this, the second-year film student finds solace wrapped in a snug blanket in front of his collection of more than 600 Beta videos. Yes, Beta— it still exists.

Valentini is a self-confessed Betaphile. He’s obsessed with Betamax, an obsolete video format dating back to the 1970s that refuses to die.

Valentinii and other Betaphiles would never use VHS (Video Home System) video cassette recorders because they say Beta is better quality. The Internet has a network of such Betaphiles to keep in touch, buying and selling Beta VCRs and movies.

Betamax was first released in 1975 by Sony, making it the VCR available to consumers. Video technology existed as early as the mid-1950s. But in the form of reel-to-reel machines that were so large and expensive, only a handful of television stations could afford them.

Until the 1970s, video was an experimental and often unreliable technology. Then Sony accomplished what many considered impossible, introducing a video format that was portable, reliable and inexpensive. In one year Sony sold 30,000 Betamax VCRs in the U.S.

Beta’s success was short-lived though. In 1976, Sony competitor JVC released VHS, setting the stage for what was known as the “format wars” — a corporate battle that would last for years.

Ever since its inception, Beta has been the superior product compared to VHS. Beta tapes are more compact and the video picture is superior.

What Beta lacked was recording length. JVC’s first VHS machines doubled Sony’s record time of only one hour. And soon other electronics companies began manufacturing and marketing VHS format VCRs.

By 1987, Beta’s market share had dropped to 5 per cent. The next year Sony tucked its tail between its legs and announced it was going to be manufacturing VHS machines, marking the end of an era. Beta was discontinued in 1991.

For Valentini and other Betaphiles, this didn’t spell the death of Beta.

“Betamax has never been dead and will not die,” Valentini says. “There are thousands of Betaphiles just like me all across Canada, the United States and Europe.

“These are people who are far more obsessed than I am. Many have home video libraries with thousands of tapes — I’m serious.”

Beta even inspired the formation of fan groups, the most famous of which, called The Betaphile Club, disbanded in 1991 after three years.

This organization had 2,000 members and rpoduced a bimonthly magazine, The Betaphile Recorder, which followed the developments of the format war while highlighting the release of new Beta products.

“But since the Internet came into being, everything has moved on-line,” Valentini says.

Beta clubs have moved to an area of cyberspace called the Betaring, an ever-expanding network of sites currently home to 15 Web pages.

Besides Web sites with schematic diagrams and technical information are sites that help Betaphiles find Beta video tapes and VCRs and offer advice.

One of the most prominent sites on the Betaring collective is the “Ultimate Betamax Info Guide,” at http://home.earthlink.net/~videoholic/, which lists every Beta VCR released in the U.S., including year, model, original price and features, and offers links to other Betaphile’s sites.

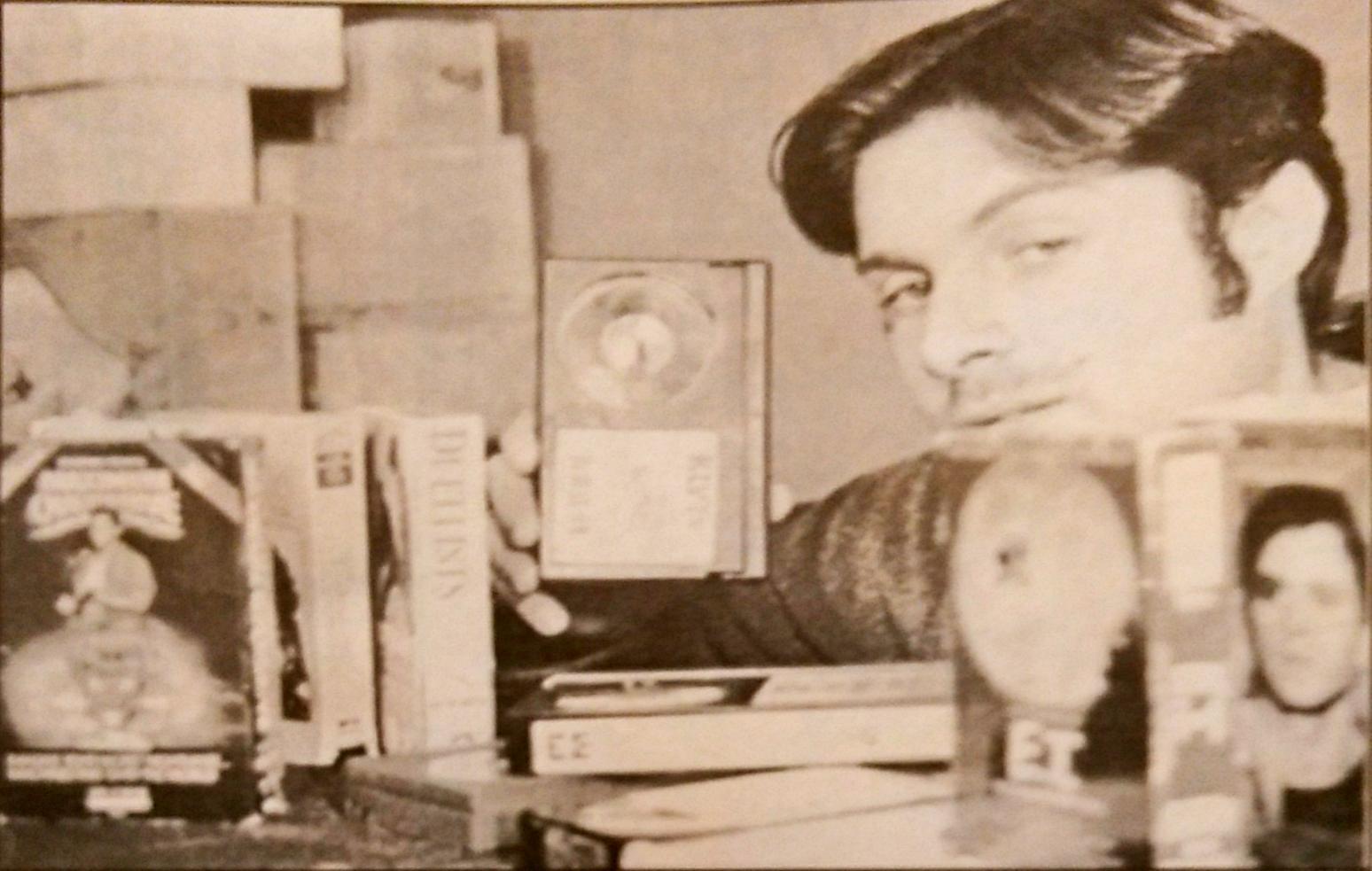

Proudly displayed in Valentini’s living room is his pride and joy, a metallic 1983 SL-27000 Beta Hi-Fi VCR, and a floor-to-ceiling mahogany bookcase stacked full of Beta video cassettes arranged in alphabetical order.

“You see that machine—it’s a second generation Hi-Fil very high-quality and all solid-state electronics. That was $2,000 machine when it came out, but now they’re so cheap that owning ten of those is not rare for people like us.”

Beta movies are sold dirt cheap for $1 for previously viewed or $2 for new videos still in their original wrapping.

“Believe it or not, but I buy brand new films for half of what it costs to borrow one from a Blockbuster for a single day,” Valentini says.

He proudly pores over his collection of Beta videos, spanning the early years of Hollywood filmmaking up until the mid-1980s, when Beta video slowly started to fade away.

“This is an original 1982 copy of [Steven] Spielberg’s ET, one of my favourite films,” he says.

Valentini reaches over to the ‘M’ section, labelled in finely inked calligraphy. “This had got to be my favourite trilogy of all time.” He pulls three videos from the bookshelf, all in their original boxes.

“This is the Mad Max series, with Mel Gibson long before he was a big name. I even have the original 1979 Australian copy, which was a very rare find.”

As Valentini shows off more of his favourites, dropping names of movies, directors and actors like an encyclopedia of cinema, two things become evident. The first is the Beta is truly alive, and more importantly, Valentini, wrapped up in his films, has managed to block out the chilly, wet, October night outside his apartment.

Leave a Reply