By Garine Tcholakian

Two grey-haired elderly men weep in each other’s arms at the airport.

Ohannes Tchalgoushian is meeting his sone Napoleon, now 65, for the first. They are reuniting in Armenia, the country they were forced to flee more than 85 years ago. Tears roll down their wrinkled faces as they hold each other tightly, feeling a lifetime of separation.

The scene is described by Artak Tchalgouchian, a third-year Ryerson computer science student. The two men at the airport are his great-grandfather and great-uncle. Like many Armenian students at Ryerson, his ancestors were orphaned and scattered around the world by the deportations and mass killings committed in Turkey from 1915 to 1923.

Tchalgouchian’s great-uncle settled in Montreal; another Armenian first-year journalism student’s mother ended up in Bulgaria, while her father went to Jerusalem; another 24-year-old mechanical engineering student’s parents fled to Iraq.

These students can tell their stories because their ancestors survived the 20th century’s first genocide.

But 1.5 million people didn’t.

In an effort to create the state of Turkey out of the remains of the Ottoman Empire, the Armenians, one of the largest native communities in the area, were targeted for extermination. All able-bodied men were forced into the army, leaving defenseless women, children and elders in the Armenian towns.

Ohannes’ family, then living in the city of Adana, was massacred by Turkish troops in 1920, while he was serving in the Balkan Wars. He had a wife named Lucine, a 4-year-old daughter named Haiganoush, and newborn son Napoleon.

When Ohannes heard the news that everyone in his city had either been driven out or massacred, he refused to return to witness the horrors. After the Balkan Wars ended, Ohannes went to Tiblisi, Georgia, and started a new family.

He didn’t know his daughter Haiganoush and infant son Napoleon had survived. They found by an Armenian freedom fighter clutched in their dead mother’s arms. Lying among hundreds of massacred bodies, Haiganoush and her brother were terrified but still alive. The 19-year-old soldier passed the children to French troops who took them to an orphanage in Lebanon, then a French colony.

Haiganoush lived with her brother in the orphanage for many years until she married and moved to Jerusalem. Napoleon later married as well and moved to Montreal.

In 1964, Haiganoush decided to move back to Armenia, even though only one tenth of the country’s original territory was left. Through a special commission organized by Armenian genocide survivors, Haiganoush was reunited with her father. In 1968, her brother Napoleon was reunited with the father he’d never seen at Armenia’s Yerevan Airport.

Another Ryerson student was told a similar story by his parents. Fourth-year mechanical engineering student Garo Sinanian, 24, says his great-grandfather was forced into the Ottoman military while his children and relatives were deported. All those living in his village, Tales, in what is now Turkey, were forced to leave and march in caravans toward the desert.

His wife, her parents and their children were told they would be relocated to a non-military zone. But they marched in circles around the desert, crossing the same mark several times. They received no food or water. Turkish special units regularly attacked and looted the caravans. “We had a lot of jewellery, so a few of us were spared by bribing the Turkish gendarmes,” Garo says.

They marched for days without being told where they were headed. As they travelled deeper into the desert, Turkish soldiers attacked and killed them with axes or burned them alive. Garabet’s aunt was kidnapped and his younger brother was killed. An Arab tribe kidnapped Garabet. He survived on small quantities of dates, yogurt and bread in exchange for his slave labour as a shepherd. For the next five years, Garabet struggled to preserve his culture by drawing Armenian letters in the sand with tree branches.

One night, Garabet escaped with a friend. After walking for days through mountains and freezing weather, the men arrived at an orphanage in northern Iraq, near the Syrian border. The last two survivors in his family, his mother and aunt, eventually found him at the orphanage.

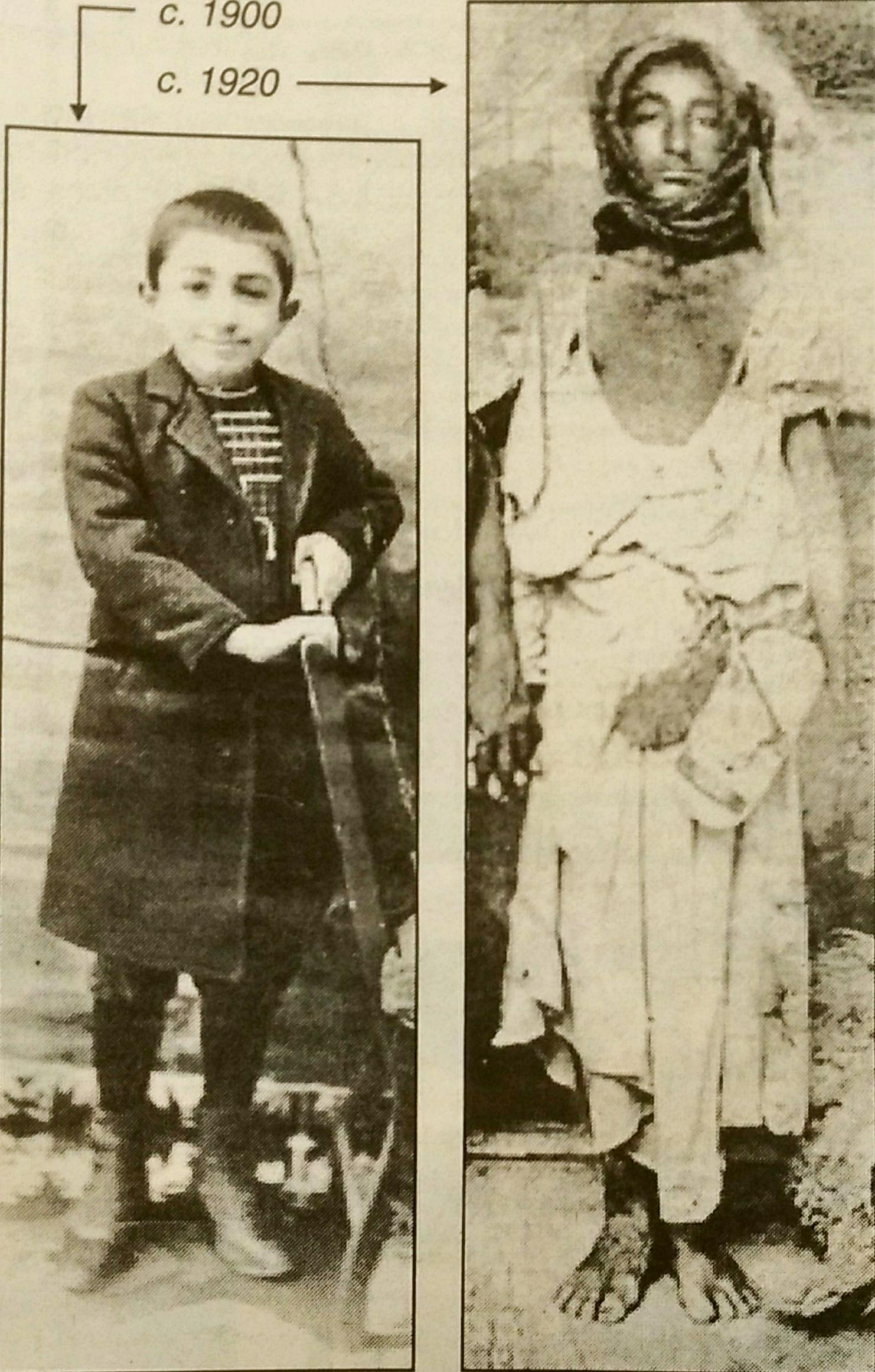

Before taking him home, Garabet’s mother had a photograph taken of her son to document his miserable condition. Garabet and his family emigrated to Canada five years ago.

Both families have flourished in Canada. Haiganoush and Napoleon now have children who have grown to become engineers, doctors and pianists. Speaking Armenian fluently, Artak’s parents say that, despite being scarred by the past, they have taught their children to live for the day.

“Hate weakens. So I don’t hate anyone,” Artak’s father says.

Artak nods his head. “They tried to do a genocide. But they didn’t succeed.”

Leave a Reply