By Michael Friscolanti

It’s as if he has never seen the video before. Gripping a microphone close to the second button of his midnight black blazer, Santiago Calatrava sharply stares at the 46-inch television screen in the southwest corner of Pitman Hall’s cafeteria. A pacifying collection of classical music carries the viewers through frame after frame of his most famous creations, and although the presentation is meant to enlighten the naive crowd, to introduce them to the Spanish-born architect’s legacy, nobody watched more closely than Calatrava himself.

His fixated eyes leap across the screen at visions of the intricate hawk-like frame he created at France’s Lyons Airport, and the simpler triangle bus shelters for the streets of St. Gallen, Switzerland. When compelled, he turns to the crowd of fewer than 100 people sitting in rows of bland wooden chairs and hums into the microphone about how his buildings copy nature’s own mysterious movements. Maybe it’s the flap of a bird’s wing, he intones in his tranquil Spanish accent, or perhaps the way a blade of grass sways in the wind.

It’s been nearly two months since the June day the university selected — or was privileged to sign — the 49-year-old architect to design what is sure to become the campus’ signature building, a 22,557-square-metre Centre for Computing and Engineering to be erected on the parking lot at the corner of Church and Gould streets. When finished, it will house nearly 2,200 students in computer science and aerospace, electrical and civil engineering. Calatrava has travelled from his Switzerland office to show neighbourhood residents a preliminary model of that edifice, one with a spiraling 33-storey tower sprouting from a main, four-floor structure.

But the architect has left the model for the end of his presentation, and as his promotional video lingers on, the crowd begins to rustle. The delay doesn’t go well with Pirman Hall’s uncanny ability to trap the scorching heat and humidity of this late-July evening. Many of those gathered are already hot and bothered over what Calatrava proposes — his creation could block the pristine views they enjoy from their lofts at the Merchandise Building on Dalhousie Street. It also doesn’t help that Calatrava, already a soft-spoken man, seems to refuse to speak into the microphone. In fits of desperation, downtown city councillor Kyle Rae, arms folded over a stark blue dress shirt that covers his chunky frame, repeatedly yells at the Spaniard to speak into the mic.

It’s not the scene that members of Ryerson’s administration, lined up against the room’s green north wall, has been hoping for. The architect doesn’t appear worried, oblivious to the anxious crowd. He’s too focused on the video, even though he’s probably already seen it dozens of times. And why should he worry about the crowd? Calatrava knows he represents what the university — and the city — so desperately wants. In a campus and surrounding neighbourhood known for brick-and-mortar boxes and simple up-and-down design, Calatrava is a potential saviour. “It is important to appreciate that I devote myself entirely to each separate project and pursue it systematically and consistently,” reads his official design approach. If Calatrava’s past projects suggest anything, it’s that he has the charm and celebrity to seduce his clients into completely believing his plans. And even though university administrators don’t even know if they can afford the building they’ve promised to the government, chances are they too will fall into Calatrava’s seductive clutches, doing everything they can to erect a truly definitive building — no matter how long the construction takes or what the price tag is.

The lobby on the ninth floor of 425 University Ave. is simple. In the centre of the light beige entranceway of G + G Architects are two leather chairs that match the colour of the walls. A table made of glass — Calatrava’s signature material — balances the two seats on the room’s east and west side.

John Greenan, a plump man whose white-collared shirt is hidden under a grey sweatshirt, has an office just off to the right side of the lobby. Greenan, one of the firm’s senior partners, says G + G applied to design the engineering building after noticing the advertisement on MERX, an Internet site used to match designers with potential clients.

Gustavo Mendez, who has been with the firm for three years and worked as Calatrava’s North American project manager, contacted the architect and sold him on the idea. “He’s an engineer and the concept of an engineering building really turned him on,” Greenan said. “We did most of the work for the proposal. It was kind of easy for him.”

That was in April, two months after the provincial government announced Ryerson would receive $54-million to build three new facilities, which include a Centre for Graphic Communications Management, a joint initiative in community health with George Brown College and the signature piece, the Centre for Computing and Engineering. Including G + G, 41 companies submitted proposals to design it. Five finalists were interviewed, but none has the international reputation of Calatrava. “I’ll say one thing for Ryerson,” Greenan says. “They got a really good deal. They didn’t pay any premium for Calatrava.” Whereas in Europe, Calatrava’s services would cost considerably more than the average architect, Greenan says the university sets its price when it invited applications. The project’s designers and engineers, which include Calatrava and G + G, will receive nearly 10 per cent of the total cost, Greenan says, which works out to about $6.5-million.

Although the selection process is confidential, it’s hard to imagine a more clear choice than Calatrava. “It’s some greater vision for the university,” Greenan says. “This puts Ryerson on the map and ahead of its competitors, in my opinion, architecturally.”

Calatrava made his mark with his ability to weave together the form and function of buildings, a quality lacking in a Ryerson neighbourhood that’s big on bulk but short on aesthetics. The proposed engineering building is highlighted by Calatrava’s signature use of glass, steel structured and repetition, reflecting his training as an architect and engineer. Calatrava studied the craft, along with urbanism, in Valencia, Spain, before studying civil engineering at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. He has left his mark in cities around the world, designing such prominent public structures as Los Angeles’ Cathedral Square, the famed Opera House in Valencia and most recently a curvaceous pedestrian bridge in Bilbao, Spain.

Although he designed Toronto’s BCE Place Galleria and Mimico Creek Bridge, he wants to enlarge the mark he’s already made in the city. “There’s very little precedent here,” says David Lieberman, an architecture professor at the University of Toronto who’s known Calatrava for 12 years, since the two were involved in the design of the BCE Place Galleria. “It’s a young country and Santiago sees it. He says, ‘here’s an opportunity to experiment.’ It is, in that sense, still the New World.”

But while the architect sees an opportunity to expand his mark in Toronto, the university hopes to gain even more, namely a building that will dust away any remnants of its old Rye High image. “You can see that when we were presented by different designs to choose from, how this one was very, very attractive,” Ian Hamilton, Ryerson’s director of campus planning and facilities, says as he looks at Calatrava’s model of the campus’ new building.

For Ryerson, it’s not just the final product that’s important, but the project’s mystique even before it’s finished. Prestige along won’t build a building. It takes money, and Calatrava’s quiet demeanour, dark curly hair, sleek accent and vaunted reputation will make him the perfect poster-boy for fundraisers who need to solicit $20-million in donations to get the building off the ground. “People will recognize him and maybe be interested in supporting it just because it’s him,” Hamilton says.

Nobody is more aware of that potential than Gordon Cressy, Ryerson’s v.p. university advancement. He works in a beige corner office on the second floor of Jorgenson Hall. Because it’s windowless — the antithesis of Calatrava’s open design philosophy — there’s not much to look at, surprising considering the man who uses it is the one responsible for looking into the community for donations. “[Calatrava’s] a good incentive for a donor,” Cressy says.

And the architect has promised to help fundraise, just short of walking door to door for pledges. When it’s time to visit a potentially generous donor, Cressy says Calatrava will be there. It’s indicative of the architect’s staying power, his passion to be involved in every aspect of his creations, long after the final portion of glass has been installed.

The managers of the BCE Place Galleria, which was designed between 1987 and 1992, still send Calatrava floor plans outlining where they’re going to hang the Christmas lights. He responds wil suggestions.

The extension to the Milwaukee Art Museum, which overlooks Lake Michigan, was only supposed to be about 5,2000 square metres. That was the plan when Calatrava was hired in December, 1994, to create the $35-million addition. Today, construction workers are still erecting the glass and steel that will make up the 30-metre, bird-like sun screen to cover the extension’s 11,250 square-metre pavilion, just one of the many extras that have blossomed with the project. In the past six years, the extension’s budget has nearly tripled to just under $98-million. Despite the price, people have fallen in love with Calatrava’s designs and keep donating money in the hopes of seeing them to fruition.

Calatrava is only six months into his relationship with Ryerson, and already the craving to go overboard exists. Calatrava’s first design of the computing and engineering building, complete with a spiralling tower, came with a hefty price tag of nearly $90-million, which would have exceeded the building’s budget by more than $25-million. Besides the overwhelming costs, Calatrava’s dreams were too grand. His tower would have exceeded the zoning bylaw for the area, which prohibits buildings from going more than 30 metres high. He also designed the structure to spill over on to the Esso gas station on the corner of Church and Dundas Streets. The university doesn’t even own this plot of land, but for a while this summer, Ryerson’s administration, too, fell into Calatrava’s dream. The architect just has that charm.

Even before Calatrava came on board, administrators has asked the city to rezone the Church Street parking lot. The original plan was a building with two-thirds of the space devoted to a four-floor structure, and the remaining one-third to a 16-storey tower. But after seeing Calatrava’s design — with a tower twice the size of Ryerson’s vision — Cressy says the university considered purchasing the adjacent Esso site, and even met with Imperial Oil during the summer. “It’s a grand dream and it’s great to have great dreams,” Cressy says, but there wasn’t enough money in Ryerson’s budget to pull it off. He says Imperial Oil was ready to give up the station, but in return wanted another area on campus to set up a new station.

The dream ended there. Calatrava’s latest design, priced around $70-million and sporting a vertebrae-shaped tower, is a step in the right direction, but it’s still too big. “What we have to is continue to pare down and pare down and force him to be more conservative with his design,” Hamilton says. “Force him to select more affordable or economic materials or select shapes that cost us less.”

Calatrava’s creativity, however, is the least of Hamilton’s problems. The $65-million meant to cover the cost of the building may not be enough to construct anywhere near the 22,557 square metres the school proposed to the government. “There’s no problem with Calatrava,” G + G’s Greenan says. “The bigger problem really revolved around the baseline budget of the program. There’s some discrepancy there, whether it’s Calatrava or no Calatrava.”

Before they can send the architect back to the drawing board, the university has to decide exactly how many classrooms and labs they need and who’s going to move where. “We have a lot of difficulties to overcome,” says Stalin Boctor, the associate dean of undergraduate studies in the faculty of engineering and applied science. “The extent of who’s moving has not been determined.”

All of these pressures lean on the tower. If something has to go, which Greenan says is the case, it will most likely be the part that would make the building most notable. “Whether or not they actually build a tower is questionable.”

University administrators say that decision hasn’t been made yet, but even Kyle Rae, the city councillor who yelled Calatrava to speak louder into the mic at that July meeting, thinks Ryerson will have to build the glass and steel structures in stages. “Today we may see the low building go forward and they would visit the tower at a later date.”

That would be evocative of Milwaukee, a project that continues to evolve. And Calatrava definitely wants Ryerson’s project to evolve. That’s why he wanted to come here. “It was a premonition,” he says from his home in Zurich, Switzerland, near one of this three world-wide offices. The others are in Paris and Valencia, Spain.

Nearly all Calatrava’s sentences end in ‘do you understand?’ a question that shows not his arrogance, but how badly he wants everyone to be clear about his intentions. In Ryerson’s case, he wants to construct a moving facade along the Church Street side of the building, one “like the waves of a lake, do you understand? The moveable facade can be enjoyed by everyone who passes by. It will underline the importance of the university to the city.”

The moving wall is an enticing proposal, but it doesn’t carry the clout of a tower, a structure that would help Ryerson mark its territory and define its campus. After seeing the first models, anything less would probably be a disappointment in the school’s eyes. “What if the tower is never built?” Lieberman asks. “Is it a building that will always look like it was never finished? Is it going to look like it was never finished? Is it going to look lonely?” Ryerson doesn’t want its signature building to be known for what it doesn’t have, but that may be the reality as Hamilton and Cressy know a capped budget and organizational details may put it on hold anyway. “We might actually be going into the ground without a completely approved upper design, but with some very good assurances of what we’re going to be doing down the road,” Hamilton says.

Calatrava has a history of enduring long roads to his visions. G + G’s Mendez, who worked with him on and off for nearly 10 years, describes his staying power this way: “I think one of the keys of his success is he creates a team approach to things,” he says. Mendez is amazed at Calatrava’s ability to draw people into his projects. When he visits potential clients, he arrives armed with a book of his past works, and maybe a few watercolour paints and a brush. Mendez says he quietly tells the person in front of him that he wants to make him part of is creation. “Draw three or four dots on the first page of the book,” Calatrava will say. After the person places his mark on the page, Calatrava will connect the dots to create a flying bird or a sleek, naked body. “In that subtle way, he intrinsically makes the people participate in his drawing,” Mendez says.

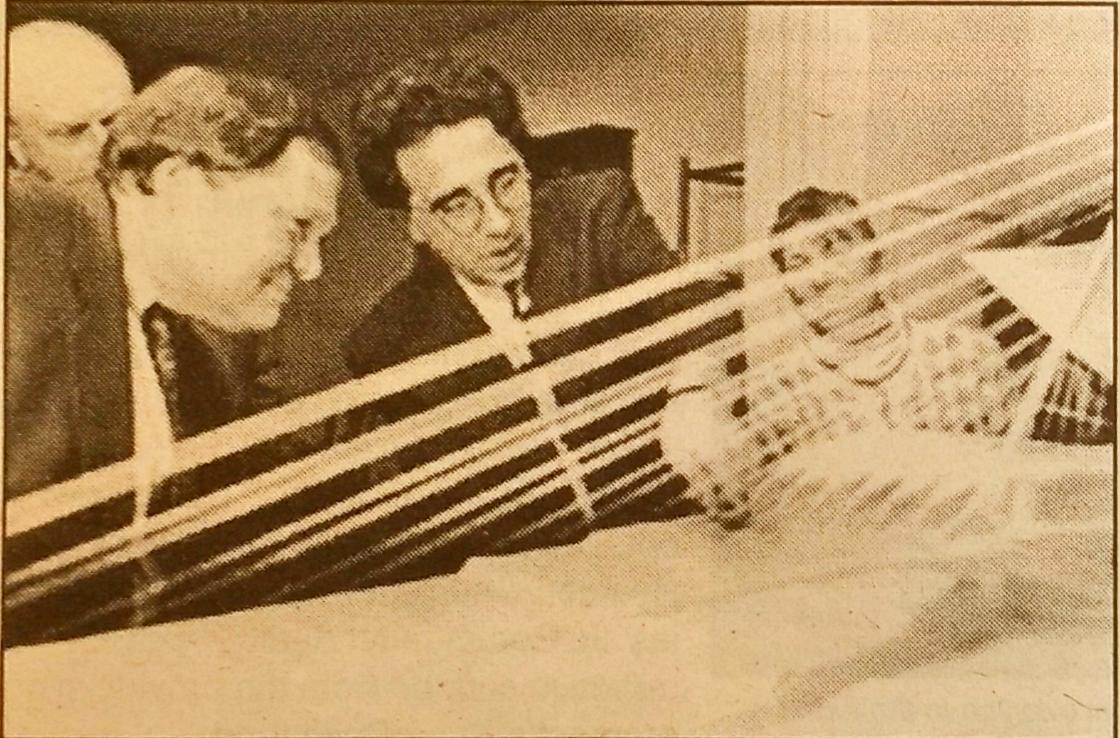

Twenty minutes have passed since Calatrava began his movie in Pitman Hall’s cafeteria, and as the music fades and the screen turns to black, the presentation shift from abstract images to a concrete finale. Only a block away from where his vision will be built, Calatrava unveils a model to the people who will be closest to its construction.

In the eyes of the university, the model reflects the site’s potential, but the experienced Calatrava sees boundaries. The tower in the model he presents today is portable because he’s not yet sure where it will go — or if it will go at all. “You cannot get everything in life,” he whispers to the crowd.

Deep down, “everything” is what Ryerson wants, a defining piece of architecture that represents its university status. Matching that with the heights of Calatrava’s ever-expanding ideas — and perhaps even earning a spot on his video — would require Ryerson administration’s utmost commitment, a complete faith in his vision. What it ultimately gets will depend on how big a shadow they want Calatrava’s landmark to building to cast.

Leave a Reply