By Gavin Mackenzie

The media arrive in flocks, trudging up the steps of Ryerson’s Eric Palin Hall with their cameras and tripods, notebooks and pens. They come to hear the Tories’ good news. Patiently they wait, crammed into a small, stuffy lab in the four-storey building. The room doesn’t even fit all the reporters who are anxious to get in. Space, it seems, is an issue this February day.

This is the very reason why Ernie Eves, the Minister of Finance, and Dianne Cunningham, the Minister of Training, Colleges and Universities, have made the trip from Queen’s Park to Ryerson’s doorstep. They have the solution — their version of the solution — to the problem of space on campuses across the province.

Ryerson’s president, Claude Lajeunesse, is there. Even a phalanx of campus security guards is overseeing the day’s events.

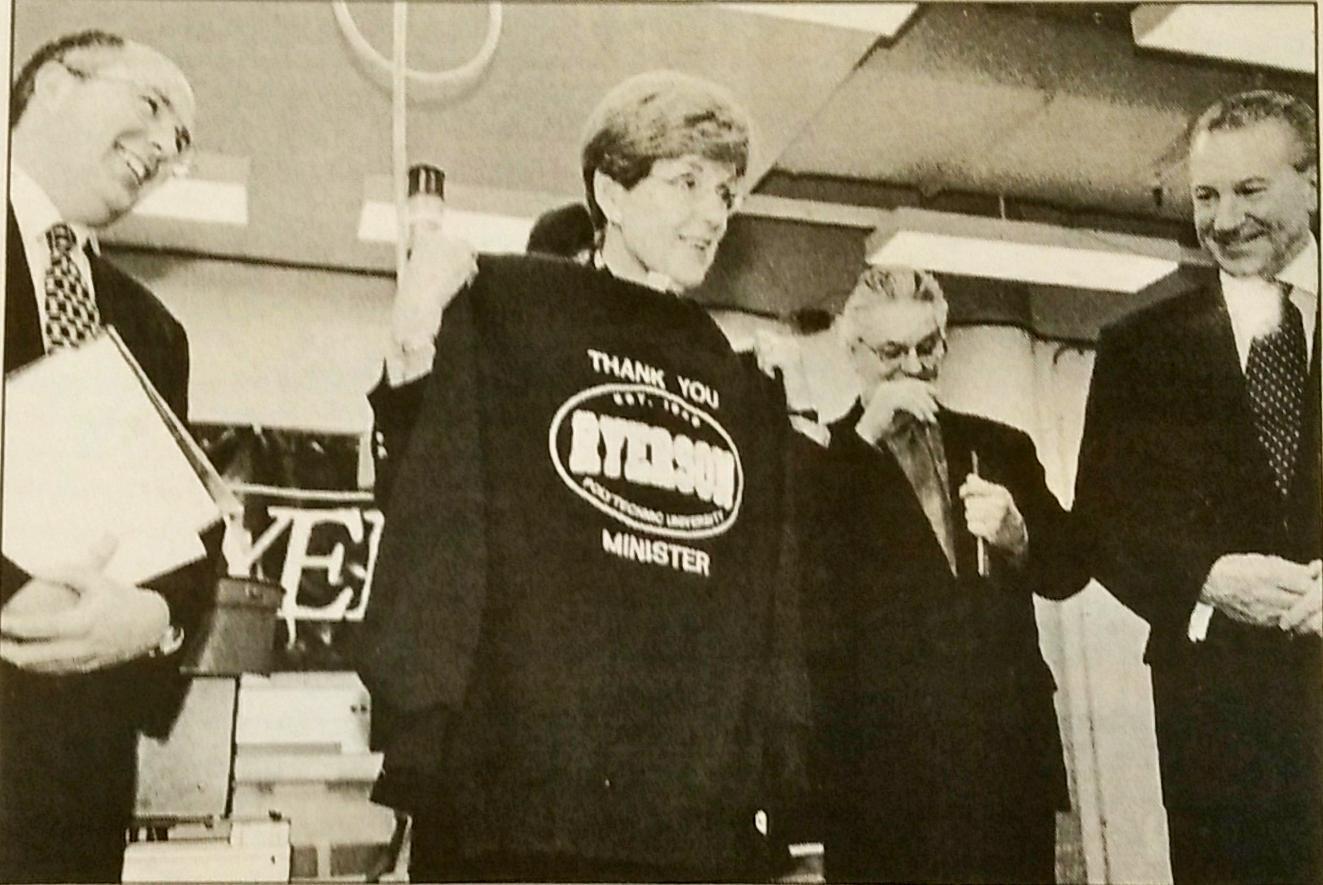

As Eves makes his way to the microphone, Lajeunesse steps in to execute a perfectly scripted photo-op. He wears a sweatshirt over his suit and tie, one with the words, “Thank you Minister” on the front and “SuperBuild” on the back. He pulls the sweater off and approached Eves, grinning from ear to ear. “Minister, I give you the shirt off my back,” he says.

While his move leaves some in the room scratching their heads, the innuendo becomes apparent as Eves reads his speech.

Beaming with delight, Lajeunesse listens as Eves tells roughly 30 members of Toronto’s media the news they’ve been waiting to hear. The province is cutting Ryerson a cheque for $54-million for the construction of three new buildings on campus: the Centre for Computing and Engineering, the Centre for Graphic Communications Management and the Ryerson/George Brown Centre for Studies in Community Health.

The projects, worth $100-million, are to be funded by the government’s SuperBuild initiative, a five-year, $20-billion plan to kickstart the private sector’s financial support to improve the province’s infrastructure. In the first chunk of spending announced last February, universities and colleges were bestowed with a $724-million windfall.

When you look at what Ryerson offered, it’s no surprise the university rallied such support. More than 75 per cent of the SuperBuild projects that will spring up in the next three years are technology-related. They will serve to fill the halls of companies that will in turn help the economy grow, a hallmark of Premier Mike Harris’ vision of postsecondary education. Ryerson fed right into the province’s hands, showing the ministry officials who evaluated proposals what they wanted to see.

“When you’re playing cards you have to play with the hand dealt to you,” said Paul Stenton, director of Ryerson’s university planning office, which shaped the proposals sent off to Queen’s Park. “The criteria made it quite clear that programs of a high-tech nature were most likely to be successful, so that was the area we pursued. Government grants on the scale of SuperBuild are so rare that you have to make the most of them, get all you can while you can.”

Post-SuperBuild announcement, more people, different setting. About 250 staff, faculty and students gather in the second-floor Commons in Jorgenson Hall to down cake, coffee and more sounds clips. Donning a white hard hat and clenching a shovel, Lajeunesse praises the Ontario government’s SuperBuild initiative.

“This is a defining moment for Ryerson,” he says. “The government has given a strong vote of confidence to Ryerson’s form of applied, relevant education and the university’s ability to help address the emerging trends in educational needs for the people of Ontario. This is great news for our students and faculty.”

It’s great news across the province that will spur a flurry of activity in the next three years. Ryerson is taking on its largest expansion in decades, which will allow it to make space for another 3,500 students, a 20 per cent increase in enrollement.

SuperBuild funding for postsecondary institutions is tied to the double cohort of students who will enter the system in three years. Grade 12 and 13 students will graduate from the province’s shortened curriculum at the same time in 2003. The government expects SuperBuild will open 57,000 more spaces for them in colleges and universities.

In early May, 1999, the spin doctoring began. The Tories released their election platform, which outlined plans for a SuperBuild Growth Fund, and announced they would shovel $724-million into campus construction that year.

Four months later, the stamps were licked and the envelopes were sealed for a mailout to every college and university in the province that outlined the criteria for applying for SuperBuild funding. Proposals were due Nov. 15, giving schools just more than a month to prepare. The package also informed those applying that money would be set aside for joint proposals between colleges and universities, and gave schools and extra month to get those pitches in.

Institutions were required to demonstrate the benefits of a project against a set of criteria that included how it planned to raise private-sector funding, student demand for the school and the programs to be offered in the new facility, and how the project contributed to the long-term economic growth of the community.

Stenton and his colleagues in the university planning officer, which conducts research for the school, had the job of structuring Ryerson’s proposals to fit SuperBuild’s criteria. His corner office on the 12th floor of Jorgenson Hall’s tower became the epicentre of Ryerson’s SuperBuild bidding.

But well before the paperwork made its way up to the 12th floor, ideas for campus development were being weighed. In the summer of 1998, months before the call for competition, Linda Grayson, the university’s v.p. administration and students affairs, approached two departments tight on space, the faculty of engineering and applied science, and the school of graphic communications management. After years of government funding cutbacks to colleges and universities, Grayson felt it was only a matter of time before the government would have to pour money back into the system.

“We knew at some time there would be funding and we needed to be ready,” she said. “Most universities have a drawer with four or five proposals ready to go, and I thought we should have one too.”

The departments worked with university planning to start developing plans for buildings, hiring architects to develop interior sketches of the projects, planning what facilities or labs they could house and estimating construction costs.

Then came that May, 1999 announcement that made it clear the provincial government had money set aside for colleges and universities. But there was no indication of how the competition would be played out, and the criteria for proposals was a fiercely guarded secret.

“We knew something was going on,” Grayson said. “But without any criteria we were totally in the dark.”

The planning went on though. In the summer, Grayson approached the late Stan Heath, who was dean of business administration, about developing a proposal to build a new business building. Heath died in September of a sudden heart attack, a shock to the Ryerson community. Lee Maguire, associate dean of business administration, decided to follow through on Heath’s proposal.

“Stan called me on my boat in the summer and told me we might have an opportunity for a new building,” Maguire said. “That fall we started working on a plan, got an architect and put together what I thought would be a pretty convincing proposal.”

When the province finally announced its criteria for those proposals, Stenton said the planning office’s role became working with what they had toward fitting the government’s requirements.

“There is a huge difference between making sure that you have the details of the buildings worked out and meeting the criteria,” he said. “Now we had to develop the case for out proposals around that criteria.” And they had only a month to do it.

Around the same time, Ryerson’s administration and members of the community services faculty began discussions with George Brown College about the possibility of submitting a joint proposal. Stenton said although Ryerson could have chosen any school in the greater Toronto area for a partnership, George Brown was chosen primarily because of its location and strong health sciences programs.

The school also decided to scrap the proposal already in the works for a new business building. Maguire envisioned a $75-million facility that would give business students a prominent face to the outside world. All Ryerson saw was the lack of land and cash.

Faced with a fund that favoured high-tech programs, and the mount of work it would take to pull off a solid pitch for business, it was left off the wishlist. “When we moved in here over 30 years ago we were told in five years’ time we would have a new building,” Maguire said, “and we are still sitting in this dilapidated old warehouse.”

Stenton said Ryerson made a strong argument that the engineering and GCM buildings would have a positive impact on Ontario’s economy, as well as fill critical shortages in the marketplace. The university went after third-party and private sector testimony to back up its position.

“With the engineering proposal there was a lot of research already done by Stats Canada and HRDC about the demand for engineering graduates,” he said. “So we basically just had to pull those off the shelf and include them in the proposal.”

But with GCM, no studies evaluated the need for graduates.

“When we got to GCM we got into a much narrower industry. You couldn’t pull a study off the shelf,” Stenton said. “So to strengthen out case that there was demand for the students, we asked the industry itself to vouch for us.”

The industry being well-represented on the school’s advisory board, the task was easy for GCM chair Mary Black. Board members have known for several years Black is itching to get her students out of the basement of West Kerr Hall. When she made a presentation about SuperBuild funding, the support rolled in. The board is made up of 17 presidents of the top graphics companies in the country. “They were quite eager to write letter,” she said, which is exactly what companies such as Quebecor and St. Joseph Printing did.

These testimonials of support were crucial to Ryerson’s success, Stenton said. “When you come forward with a proposal where you have strong support for your argument, and you can point to someone else saying it, rather than you just asserting it, it really strengthens your case.”

Another secret to Ryerson’ SuperBuild sweepstake was securing private-sector funding. At the time GCM’s proposal was submitted, Ryerson had already raised $4-million of the $6-million it needed in donations. Gordon Cressy, v.p. of university advancement, said this created a comfort zone that showed Ryerson could raise money quickly.

No donations have been secured yet for the engineering and community services buildings. Cressy said money for those projects will come from letting private sector donors attach their names to the buildings.

It wasn’t enough for Ryerson to show how much it could fundraise to contribute to the project — the government wanted to know how much money the facilities would contribute to the economy. This was easy to demonstrate with the engineering and GCM buildings, Stenton said, but with the community services buildings, Ryerson argued creating a new gerontology program to be run in the facility would have a positive impact on the community. “Gerontology is a new program, but considering the demographics of our aging country, it wasn’t hard to identify a demand,” he said.

OVerall, Ryerson’s bids projected the programs to be housed in the three new buildings would contribute $75-million annually to Ontario’s gross domestic product, with an employment increase of more than 600 people a year in the health sciences, graphic communications and engineering fields. Ministry statistics say applications for science and high-tech programs has increased 27.5 per cent over the past 12 years, while the interest in arts programs has declined 28.5 per cent.

Ryerson then had a proven student demand for the programs it planned to expand, since all are science or high-tech related.

Not until February morning did Grayson find out how well Ryerson had scored. “We’re an applied university and the kinds of projects we put forward reflect who we are and the kind of education Ryerson stands for.”

Critics say this is exactly the problem with targeted funding such as SuperBuild. There’s a bias against liberal arts studies because not every student wants to be trained directly for the workplace.

“The provincial government has made it very clear in the past that they care very little about the arts and humanities,” said MPP Rosario Marchese, the NDP’s education critic. “SuperBuild put these beliefs into practice.”

The schools left out of the first round of SuperBuild spending include the Ontario College of Art and Design, which wasn’t approved for funding until after last spring’s budget, when the Tories realized there was extra cash left over.

Linda Nicholson, a media relations officer at the ministry of training, colleges and universities, said there was no intended disregard toward the arts and humanities.

“Schools that were successful in SuperBuild simply met the demands of the criteria,” she said. “When you look at the amount of money that was handed out, it just makes more sense that it should go to the areas that are more valuable to the growth of the economy.” Engineering and gerontology are perfect examples.

“The criteria only played to the hands of the schools with a commitment to high-tech programs,” Marchese said.

Lajeunesse solidified that commitment when he placed his “Thank you Minister” sweatshirt in the Finance Minister’s hands.

Leave a Reply