One-time Ryerson student Colleen Murphy reflects on her controversial new play, The Piper

By Gabe Kastner

You would think that after making three well-liked feature-length films, numerous shorts, a play, and a musical, Colleen Murphy would be satisfied, or at least a little proud.

“I consider myself a total failure. I barely make a living, I can barley keep my kid in school,” deadpans Murphy at a coffee shop near Factory Theatre (125 Bathurst), where her most recent play, The Piper, took the stage until this Sunday, March 3.

It’s inspired by the story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin and performed in a manner stylistically opposite to the super-naturalist style of most of her other work.

The opening night, Feb. 14, wasn’t a smash hit, but it certainly didn’t bomb either. Rather, it was reviewed in every major Toronto newspaper, its criticism actually developing into a minor cross media debate.

“It’s gotten slaughtered on many levels, and also defended very well on many levels,” says Murphy.

The slaughtering came from Eye and a bit from the Toronto Star, while the best defense came from Ray Conlogue of the Globe and Mail, who stood up for The Piper in a column on Feb. 27 to express his disappointment in Toronto audiences for not being open to its unexpected style.

“[The Globe article] is dead on,” says Murphy, “Ray got it.” The Piper is a work of expressionist theatre, a healthy jolt to our bored brains in this mostly-European style developed by Bertolt Brecht in Germany in the 1920s to catch the viewer off guard and surprise them.

“You don’t have to say ‘This is expressionism, therefore you have to put the expressionism glasses on in order to appreciate this,’” she says. Basically all you have to do is have an open mind, and allow the material to just unfold in front of you.”

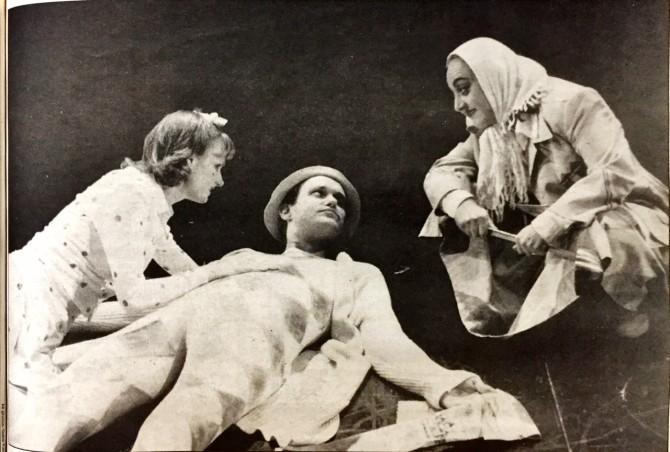

From its opening moment (in the woods, on a mountain’s peak, a young nightmare-stricken boy screams as he writhes on the ground) to its closing more than two hours later (in an afterlife, a British-accented rat-person quotes Nietzche and consoles the boy), we were caught off guard, never fully able to keep up with the play’s indecipherable, turbo-speed rhythm. The second scene sets the tone for most of the rest of the play. It is a punishingly long town council meeting for the city of Hamelin. A council of ten colourflly-clad Mel Lastman types argue, debate, and clown around over everything except their city’s needs.

I wasn’t sure whether I enjoyed the play for at least an hour after it ended. Once the chaos that had been stirred in my mind began to settle, it became clear that the show was actually a glorious spectacle of characters and ideas.

“When you read the script you see that much of the writing is in bold caps. It’s exclamatory theatre in a way,” says Murphy.

If she doesn’t think she has succeeded with her work, Murphy must at least be happy to be doing what she wants, writing scripts and directing films, right? “Actually, I wanted to be a downhill racer. I hurt myself so I ended up going into theatre, but I wanted to be, very much, a downhill skier.”

Born in Rouyn-Noranda, Quebec, a small town surrounded by bush, Murphy’s father was a miner in Northern Ontario and her mother a homemaker. “Catholic school, music training and sports — under all that lay the swamp called childhood.” Her downhill racing dreams shattered by an injury, she painfully resigned herself to a life without skiing and decided to take up theatre instead.

Although she took only one year of acting at Ryerson, in the early ‘70s, she has fond memories.

“I was with a bunch of gals who since have made it in theatre in some form. Mary Walsh from This Hour has 22 Minutes, Sonja Smitts. Debra McGrath was a fantastic actress and a fantastic voice person, and Jennifer Dean, who was with the Hummer Sisters for a long time.”

Unsure of her choice of career, she tried another acting program, at the Strasberg Institute in New York. She had a wonderful time in the Big Apple, but returned to Toronto after one year to play parts in a few local productions before finally deciding that acting was not her thing. “I wasn’t that good at it and I had very bad nerves.”

Murphy began to take writing more seriously, whereas she had previously seen writing more as a hobby. “I always wrote bad poetry. I always wrote ever since I can remember.”

In 1989 her script Termini Station was filmed starring Anne of Green Gables’ Megan Follows and a host of other top-quality Canadian actors. The film is an intimate and witty look at a working-class Ontario family, devastated by suicide and some other painful circumstances. It premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and was shown in at least three other festivals, and was nominated for five Gemini awards including one for Best Original Screenplay. Yet when I bring up the film, Murphy shrugs it off with an embarrassed “Oh, that one’s old,” and is surprised to hear how much I enjoyed the film.

Murphy directed Jaan Kolk’s script for Shoemaker in 1996. In between features, she also directed several shorts: Putty Worm in 1993, The Feeler in 1995, and War Holes, a silent film protesting the killing of children in war, filmed on September 8th of last year.

Although Colleen Murphy has a tendency for self-depreciation, she clearly has not let it stop her from creating a range of fascinating dramatic works in several genres. If she is a failure, she’s certainly not taking it lying down. When asked for a final message to the students of Ryerson and other youth, she had four words that illustrate just what kind of ‘total failure’ she is.

“Refuse to be silent.”

Leave a Reply