By Phillip Stavrou

School books: $400.

Drinking through frosh week: $150.

Tylenol and coffee to recover from frosh week: $11.

Maxing out your credit card and pretending to cry so your parents will give you money: Priceless.

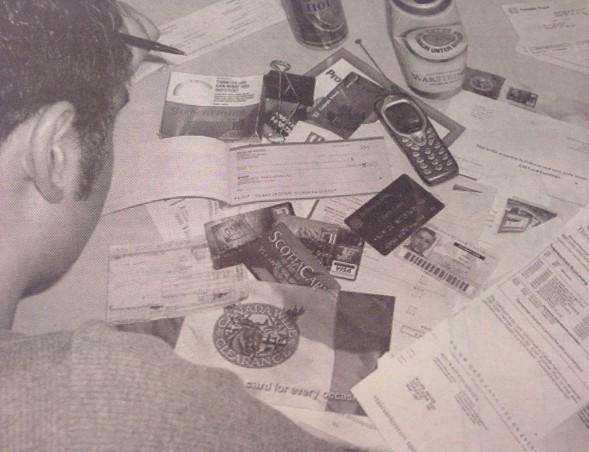

Every fall, credit card companies rush campuses, pushing their product on naïve students eager to spend “plastic pennies”. Their cries of unconditional credit and offers of free T-shirt lure students to their tables during Frosh Week, promising them lines of credit as high as $1,000. Most applications are approved whether you make $500 a month or $500 a year, sending students on a spiral into that infamous black hole — debt.

Sandra Fortino, a fourth-year ITM student at Ryerson, has accumulated $830 in debt over the past two months. The money has gone into things like gas for her Cavalier, a camping trip in Quebec and eating out at local pubs.

“It will probably take me about six months to pay it off,” says Fortino, despite the $800 she earns each month working for a market research company. “[The debt] doesn’t weigh on my mind a lot ‘cause the debt is kind of new. I would like to pay it down before May but chances are I won’t be able to until I get a full-time job.” Fortino, who carries two credit cards with $1,200 and $1,500 credit limits, got her first card at the age of 19 as an incentive for opening an account with a new bank.

Students in particular are targeted by banks and credit card companies because they want to secure clients now for the long term, says Sandra Sherk, executive director of the Credit Counselling Service of Durham Region. “If they get them now they could have them for 50 years. It’s not uncommon to see [places] on university and college campuses where you can fill out one application form and apply for a lot of credit cards.”

Many students don’t fully understand that they eventually have to pay for all the purchases they make, says Sherk. Born into a “plastic society”, students may have seen their parents using credit cards while they were growing up. What they didn’t see was their parents paying the bill at the end of the month.

It took four months for Alex Husarewych, a second-year ITM student at Ryerson, to pay off his $900 credit card debt. Used mostly to buy Christmas gifts and clothing, his credit card textbooks. Without any cash left in his bank account, he was forced to buy $600 worth of books on credit.

“I have no choice,” says Ramcharan as he stands in line at Financial Services. “I had to pay $1,000 down-payment on tuition plus a $400 deposit to reserve my spot, so that’s basically the money you earn in the summer time.”

While Ramcharan plans on paying it back, he is still going to have to pay the extra interest charges. “I’m going to pay it off but over a longer period of time probably putting $50 in every month,” says Ramcharan.

Most bank-sponsored credit cards carry interest rates of 15 to 20 per cent, while cards issued by retail outlets like The Bay or Canadian Tire can reach as high as 25 to 30 per cent annually.

The spiral begins if students can’t make the full payment at the end of each month. Even if they commit the minimum payment of around two per cent, students will still get charged interest on the balance.

The sentiment that credit cards can be used in lieu of income is one that needs to be re-evaluated, says Sherk. “In order to service a credit card you have to have money coming in … if you think of a credit card as an extension of your paycheck, it isn’t. It’s not free money. It’s basically a convenience for buying something now and paying for it at the end of the month.”

Often students do have the money to make their minimum payment but forgetfulness prevents them from making it, says Monica DeClara, branch manager of Metro Credit Union in Ryerson’s Jorgenson Hall. If a student is consistently late they will have a hard time getting any more credit because credit trouble can affect their record for up to seven years.

Since credit cards are readily available, students need to educate themselves about finance and credit, says DeClara. “You can get it by basically looking up seminars that banks and credit unions do offer about handling credit. There’s lots of information about handling credit. It’s something that you can actually get used to.

For students already in debt, the first thing they should do is cut up their credit card, or cards if they have more than one, then sit down and make up a spending plan, organizing their income, expenses and credit obligations, says Sherk.

“The flexible expenses, the lunch money, the entertainment money is where they may have to make some changes so they have the money to repay the creditors,” she says.

Students should ask themselves if a credit card is really necessary and make sure that they can make substantial payments every month. The bottom line: Credit cards should only be used in emergency situations.

“none of us should have emergencies every day,” says Sherk.

“If you are going to get one, use it wisely,” adds Fortino. “Don’t go maxing it out if you know you can’t pay it. It’s available, it’s like cash. It’s easy to forget that you have to pay it.”

Leave a Reply