By Ab Velasco

My shrink tells me that Survivor is just a game, but when Shii Ann Huang was voted out two weeks ago, I felt like my life had ended. I wanted Penny Ramsey, the contestant who organized her ousting, to burn.

Since its debut in 2000, Survivor is credited with sparking the reality TV phenomenon. It added the terms ‘tribal council’ and ‘immunity challenge’ to everyday lingo.

People throw parties and sit in front of televisions, cheering the contestants they love, and anxiously awaiting the demise of those they hate.

And I’m not the only one who hates Penny. Over at a Beverley Street basement, a group of Ryerson and University of Toronto students gather for their weekly party.

Anna Samulak stares at the TV. “Look at her ears. She’s got ugly ears,” she says of my nemesis. “I don’t want her to win.”

Doug Stiles nibbles on some popcorn and laughs. “So you don’t want ugly people to win?”

“Not if they’re ugly and evil,” she pauses as Penny hatches her latest scheme. “Bitch!”

Canadians are huge Survivor fans. Neilson ratings say that one in seven of us watched the premiere of this season’s Survivor: Thailand. Yet, for some reason, only Americans can compete for the million-dollar prize.

But on Sept. 17, a glimmer of hope entered my life. Executive producer Mark Burnett announced in an interview that he might add Canucks to the mix. “Americans and Canadians have the same kind of accent, a bit, apart from you keep saying ‘eh’ all the time.”

I want to be part of Survivor history. I often listen to the theme song and imagine myself competing, with black war paint streaked across my face, as the ancient voices chant “eh-e-yo-ye-yo-ye-yo-ye-ya-ya.” So I set out on a quest, seeking the wisdom of one castaway from each season.

For each instalment of the show, more than 80,000 people fill out the online application form on CBS.com. They send in an accompanying audition tape.

Robyn Jass, the casting director of Marquesas and all the Big Brother shows, says that simplicity is all the key.

“A lot of people try to eat bugs and hold their tiki torches. That is the stuff that we don’t like, because we can’t get a feel of who the person is,” Kass says.

The 80,000 applicants are narrowed down to 500semi0finalists who are sent to 10 designated regions across the States for a 10 to 30 minute interview.

Jeff Varner, the seventh person voted off Survivor: Australia, says the trick is to be yourself. “They [the application processes] are designed to trip you up and catch you in lies. If there is something about you that would kill you if anyone found out, you can bet it’ll come out there.”

The 500 are narrowed to 50 finalists and flown to a hotel. They complete an IQ test, a quiz that asks stuff like “do you hear voices?” along with more than 3,000 other questions and a physical check up and endurance tests.

The final interview focuses on strategy, says Kass. “We get people who say they will lie, or use the boys. You have to have a mix of people who will play the game in different ways.”

The final 16 are picked by CBS executive Les Moonves. “He wants to get a genuine feel of the personality. Moonves takes a range of circumstances into account, such as where the applicant attended college and why they want to leave their family for two months.

The rules have not changed much since the show first premiered. Sixteen strangers are still stranded on a remote island for 39 days and forced to form a new society while competing against each other.

They start off as two competing tribes of eight. Every three days, the team that loses the immunity challenge goes to tribal council to vote out a member. When 10 survivors are left, they merge into one tribe and compete for individual immunity. The eighth to 14th survivors ejected form a jury of seven, who vote for the winner.

In the end, “Outwit, Outlast, Outplay,” the show’s slogan, defines the winner. The past four winners are as different as day and night. The original Survivor winner, Richard Hatch, was a calculating snake compared to Survivor: Africa’s Ethan Zohn, who was an all-around nice guy.

Lex van den Berghe, who placed third in Africa, says people get what they sign up for, even if it means obtaining their water from a creek that doubles as an elephant’s toilet.

“Mark Burnett is a tough motherfucker,” he said. “But human beings by nature are survivors. We experienced what it was like to starve, but we managed to make good.”

Some desperate original Survivor contestants feasted on rats. Ramona Gray, voted off fifth, said in an online chat that “rat does not taste like chicken. Rat tastes like rat!”

Hunger, further agitated by the stress required to advance in the game, often leads to paranoia.

“It is almost the 17th player,” Van den Berghe says. “It creeps into every person’s psyche. No matter what alliances you make, or relationships you make, you are a team of one.”

His advice to wannabe survivors is to accept that it’s just a game. “I got the most votes out of anyone in Africa, but I just told people after each tribal council, that it was okay.”

Starting in season three, the producers introduced twists to keep the game fresh, including a tribe shuffle, which re-arranged the tribes midway to the merge. There are also twists of fate that can’t be controlled. In Australia, the Kucha tribe seemed destined to enter the merge with a 6-4 person advantage over Ogakor.

Before the immunity challenge, Kucha member Michael Skupin was fanning the fire and fainted when he inhaled smoke. He fell onto the fire and was taken off the island and later exited the game. His exit arguably changed the game, leading to a win by Ogakor’s Tina Wesson.

What is alarming is that the cameramen who follow the contestants 24/7 are not only forbidden to speak to them, but can’t intervene in these situations.

“It took about 45 minutes to get Mike out,” says Varner, a former Kucha tribe member. “The crew got the appropriate personnel, but you are not protected from danger. You are given medical attention quickly [when you ask]. It’s real.”

Sickness can’t be controller either. Tanya Vance was voted off second from Thailand, because she became sick and her tribe mates saw her as a handicap.

“When you’re outdoors and have no fresh water to drink or food, it’s hard to get better,” she says. “Hiding it isn’t even an option. You are with these people 24 hours a day.”

Altogether, 936 hours of footage are whittled down to just 16, leaving the plenty of mundane action on the cutting room floor.

Tammy Leitner, who placed seventh in Marquesas, says that boredom was a big issue. “We had so much down time. When we weren’t cooking, which took four hours to prepare the one meal we had, we sat down and got to know each other. We spent hours fantasizing about food.

“If you add up the time we spent together, I spent more time with these people than I have with some of my best friends.”

In the end, most contestants agree it’s all about politics. Some play the honest way, but the majority have resorted to back-stabbing and forming alliances. After all, there is strength when voting in numbers.

Van den Berghe’s third-place finish in Africa was partly due to his alliance with fourth-place finished Tom Buchanan and contest-winner Zohn. “We decided from the very beginning that one of the three of us was going to take home the million dollars,” Van den Berghe says.

However, Leitner advises would-be contestants to hold off on making alliances. “Make sure you really know the people,” she says. “Although I loved everyone on my alliance, John 9Caroll], couldn’t keep his mouth shut. He had to keep making announcements about our next big plan.”

In Leitner’s case, her alliance backfired when a disorganized five banded together and picked off her four-person alliance one by one.

Even when the game is over, many survivors take home post-game stress and other less than pleasant souvenirs of their time in the wild.

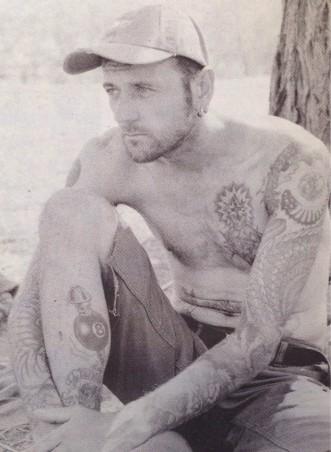

Van den Berghe returned with seven parasites and various bacterial infections. He also suffered mental trauma.

“The game of Survivor leaves you damaged,” he says. “You spend more than a month building these walls around you, so you can’t just knock them out right away.

“It took me a couple of weeks to feel comfortable indoors. All I wanted to do was to sleep in my backyard.”

Leitner says you have to love yourself beforehand. “I loved my life before going to the island. I loved my job as a crime reporter. I think the transition may be hard for some people who come back, because they saw Survivor as a way to change their life.”

Stress or not, the contestants on the show have enjoyed a generous time in the spotlight. Some have appeared in feature films, charity events and soap operas.

Varner, who stars in the upcoming TV movie Area 23, says the notoriety is a double-edged sword.

“Imagine being asked the same questions over and over and over — get my point?” he says. “I’m grateful and loved the experience. It just becomes hard to do the normal things that you did before.”

But the more losers the show spawns, the more former Survivor contestants become less of the hot commodities they once were. The show itself, however, is still earning healthy ratings.

“I think it will always remain popular,” says John Powell, senior news editor at Canoe.ca. “The other stuff on television now are retreads and recycled sitcoms. When compared to that, what would you rather watch?”

Survivor is still a runaway hit in Canada, so it is only a matter of time before Burnett makes good on his promise — and I’m not talking about an imitation hosted by Pamela Wallin. I mean, what good is $1 million Canadian anyway?

Van den Berghe’s final piece of survival advice: “Just kick ass!”

Leave a Reply