By Diana Hall

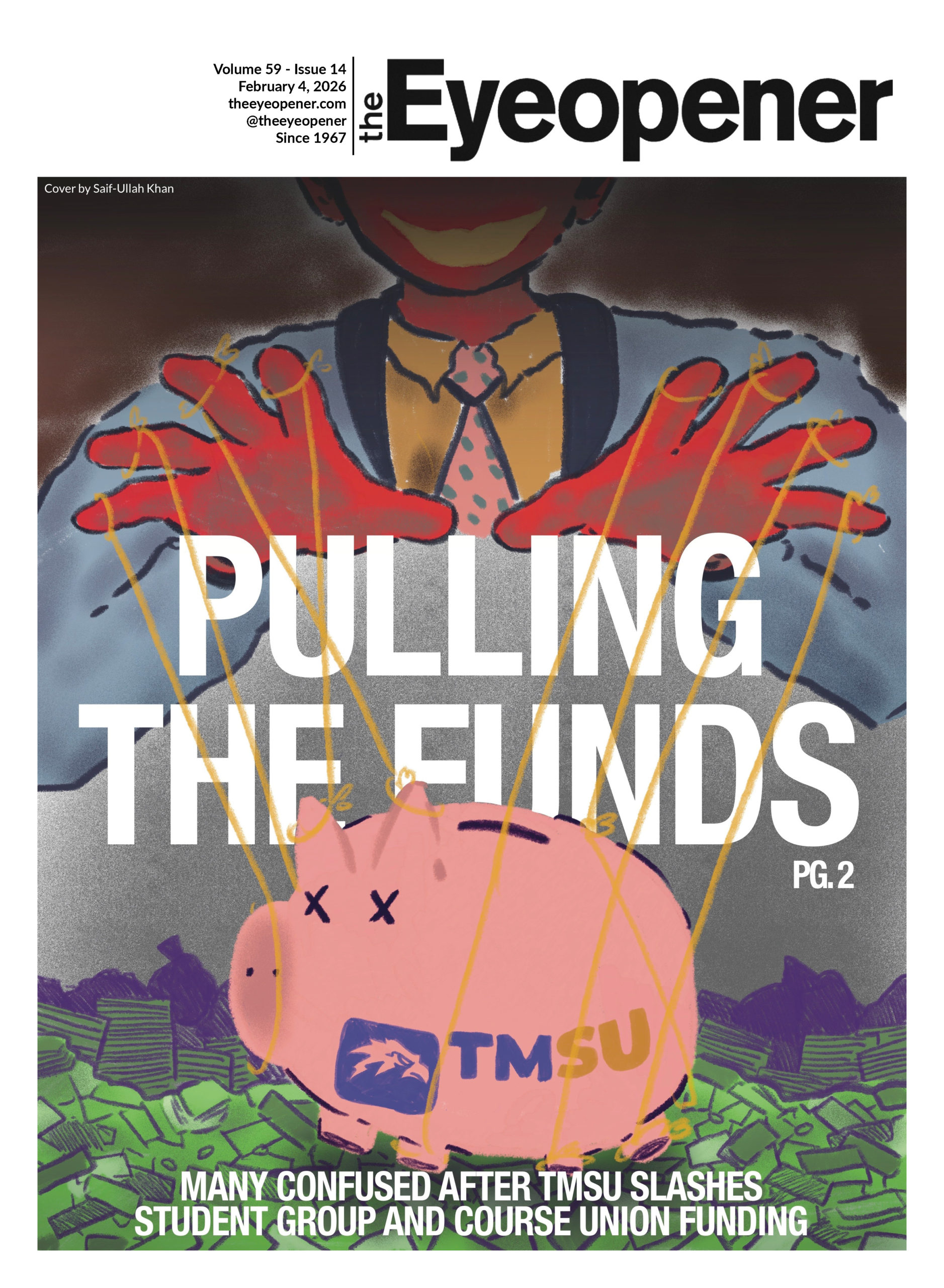

Home is where the heart is, and Ryerson is unapologetically vying for the heart of Toronto. It’s all part of Ryerson President Sheldon Levy’s Master Plan, a strict blueprint for success.

But east of Pitman Hall and the Rogers Communication Centre lie dusty corners of a land-locked campus where the pieces just don’t fit.

The Master Plan presented an ultimatum to the university in 2008: to avoid being swallowed up by Toronto’s downtown core, Ryerson would have to shed its past as a polytechnic institute. It was an image bolstered by a dreary, dispassionate campus of a comfortable 21 acres.

Since then, a storm of construction has transformed the campus as well as the landscape of the downtown core. The Mattamy Athletic Centre is diligently celebrating the re-vitalization of Maple Leaf Gardens to the north; the face of Yonge Street will soon be graced with the sleek, glass Student Learning Centre to the west; and the Ryerson Image Centre will finally open its doors to community members on Gould Street on Sept. 29.

But the East side of campus, a mere four blocks away, lacks strategic appeal, opportunity and major access routes which the university could capitalize on.

“[This] was really part of what Sheldon articulated in his speech when he was installed around making sure that there wasn’t anyone who wouldn’t know where Ryerson was anymore,” said Julia Hanigsberg, vice president administration and finance. She emphasized that the idea of creating a gateway into Ryerson from “Canada’s main street” will be monumentally influential for the university.

Levy said the university’s interest wanes when project developers propose to push campus borders past Jarvis Street. It marks the boundary of an unnerving territory for the city of Toronto, one that is underdeveloped, and home to low-income families, the mentally ill and homeless shelters. If the university expands its borders, it can’t afford to sprawl in a way that affects student access to university services (plotted, you guessed it, to the West at Jorgenson Hall).

That’s why Levy wants to see more infilling on campus, an endeavour easier said than done for Ryerson, in particular.

“Because of where we’re located, almost all the infilling means to secure a property that someone already owns. That’s the difficulty,” Levy says. “You can think of expropriation, but you can’t expropriate everything. And everything is expensive.”

The ghostly building at 111 Gerrard St. (across from Sally Horsfall) serves as a reminder for the university to choose sites wisely, even if the price is high. Still, it’s hard to believe that a university so determined to prove itself as a cultural landmark in Toronto could allow such a space to sit empty and unused. The strategic service doesn’t exist and so, it waits.

The school’s ultimate intention is clear: Ryerson is focused on branding itself as a staple in the City of Toronto. Above all, the university is ready to put money where its mouth is.

Leave a Reply