By Nikhil Sharma

Eating bread with eggs, butter or jam for breakfast is a ritual at Ryerson student Monica Mejia’s household. But her four-year-old nephew is gluten intolerant and can’t join in.

“Knowing that he won’t be able to do that, it’s heartbreaking,” Mejia, a fourth-year global management student and volunteer at Ryerson’s Good Food Centre, said. “So we have to find alternatives for him to replace that.”

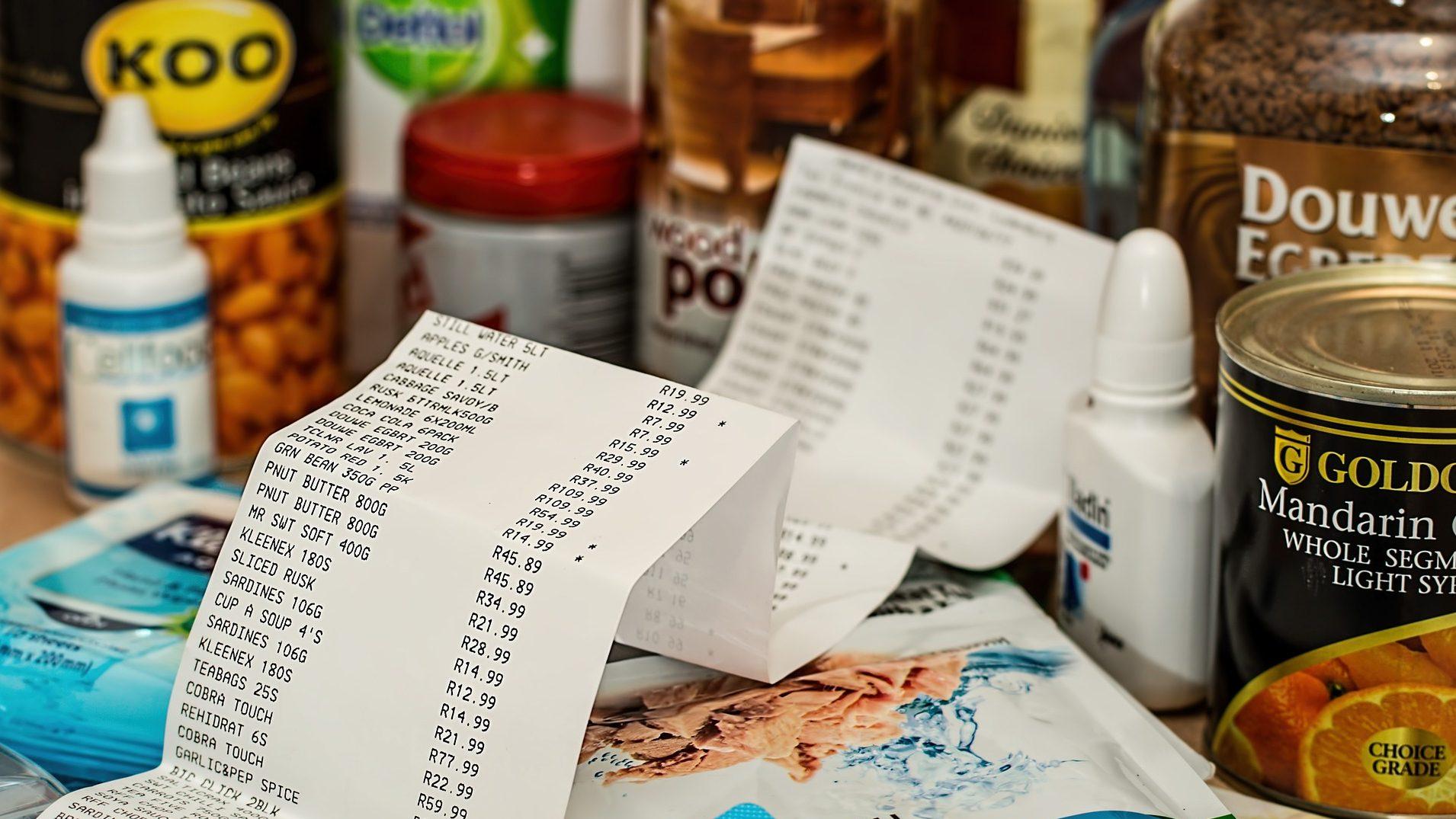

Her family has to be extremely careful in what they purchase at the grocery store to make sure every single item they’re buying to make meals for her nephew is safe for him to eat.

Even though some bread can be gluten-free, Mejia said there is no guarantee it won’t contain wheat or that its ingredients won’t have come in contact with something that has wheat in it. If her nephew eats gluten, his stomach gets bloated, he loses his appetite and starts to lose weight.

Fruits, vegetables, wheat and meats can be subject to inaccurate labeling. Sometimes that can mean an incorrect country of origin. Other times it means a product may not contain what it says it does. The milk you buy from the supermarket may not come from a cow, corn syrup can be in a bottle that is labelled as honey, and the frozen pizza you buy may not really have ham and cheese on it.

This is called food fraud, a multi-billion-dollar crime that affects retailers and consumers. Researchers are looking for ways to put an end to the problem, including letting people make a difference right in their own backyards.

The Good Food Centre (File photo)

Economic adulteration and counterfeiting of global food and consumer products can cost the industry $10 to $15 billion annually, according to the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA).

Manufacturers and suppliers intentionally commit it to earn a big profit. Suppliers and manufacturers are responsible for packaging and labeling, which carries product information, including common names, ingredients, net quality, durable life date, names and addresses of manufacturers, dealers or importers; and sometimes grades, qualities and countries of origin. There are seven different types of food fraud, including adulteration, tampering, overrun, theft, diversion, simulation and counterfeit.

Ontario poultry producer, Cericola Farms Inc., was a supplier to the largest grocery stores in the country, including Costco, Loblaws and Sobeys. It was charged in October for allegedly mislabeling conventional chicken as certified organic, after an investigation by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA).

The largest investigation for the agency took place in January 2012 following a three-year investigation into Mucci Farms and its greenhouse peppers that were labelled as being a Canadian products outside of the carton, but as a product of Mexico on the inside.

While CFIA sets the regulations and policies for imports, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) shares the responsibility for enforcing them during their initial inspection of food, agricultural inputs and agricultural products at entry points.

CFIA conducts an average of 3,000 food safety investigations per year. When the agency’s complaints and appeals office (CAO) opened in 2012, it found 167 of 318 files to be outside of their mandate. Many of the complaints were related to food labeling and potential foodborne illness.

According to CFIA, the agency received about 40 consumer complaints per year between 2012 and 2015 with concerns about possible food misrepresentation.

Whenever CFIA receives a complaint from a consumer, it follows up on the issue by inspecting the product or label. If noncompliance is identified, the inspector notifies the regulated party and requests corrective action within a time period based on the severity of the risk to human health.

Once the follow-up with the regulated party is finished, CFIA informs the consumer whether or not the product or label was compliant or non-complaint.

Evidence from computer records, emails and three search warrants at the Kingsville, Ont., headquarters showed Mucci Farms had been selling products worth more than $1.4 million that were imported as Canadian at grocery stores in Ontario.

Mejia has always questioned whether organic foods are legitimate or not because of the certain standards that need to be met for products to be sold as organic.

Researchers at the University of Guelph’s Biodiversity Institute of Ontario have been using DNA technology, such as sequencing barcoding, to test to see if the fish you buy at the store is indeed the kind you thought it was.

DNA barcoding was proposed by the university’s professor, Paul Herbert, in 2003. It’s a way to identify and differentiate species with a slight fragment of DNA from a single gene such as cytochrome c oxidase 1 (CO1) found in the cells of all animals.

In order for CO1 DNA sequences to be completed, a specimen is collected and identified by a taxonomist. A tissue sample is obtained from the specimen and digested to make the DNA accessible and extractable. The DNA is then amplified using a process called polymerase chain reaction, which makes copies of the gene fragment for sequencing. Once the DNA is sequenced to generate a barcode, that barcode is entered into the Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) database—a reference library which helps researchers across the country collect, manage and analyze DNA barcodes.

Each entry includes information on the animal’s taxonomic name, picture, GPS coordinates where it has been found and its barcode sequences.

This is a valuable tool to detect food fraud in the meat industry.

DNA barcoding can also be used to monitor biomaterials crossing international borders and verify plant or animal ingredients in foods.

A scientist records data in a lab

Guelph’s Biodiversity Institute of Ontario also developed the LifeScanner app in collaboration with SAP Canada. It allows people to use DNA barcoding to discover the living organisms around them and provide scientists access to more data and resources.

A LifeScanner kit has vials, which are used to keep collected samples, such as fur, an insect, raw meat or a leaf. A QR code is read by the app on every vial, which connects the sample with geographical and other information to assist scientists with analysis in a lab.

Users can then track the analysis and receive data on the species they’ve come across from their smartphones.

Mejia says an app based on DNA barcoding could fix the lack of communication from local supermarkets about the food they’re being sold.

In September, senior biology and science students from across the country took part in the Fish Market Survey Action Project. They went to local grocery stores, collected samples of fish, used the LifeScanner kit to collect data on where and when the fish was collected, and how they were labelled. The vials were then sent back to the lab at Guelph to be DNA barcoded. The analysis will reveal what species of fish were collected and if they were labelled accurately.

“I think in a way it would be great to have access to that information that is not provided to us and that also we may not even know we need or have access to,” Mejia said of a DNA-based identification app being available to the public.

“I think knowledge is important, but I also find that our generation is very comfortable in the sense that we don’t have a lot of time on our hands,” she added.

“As a student, just thinking about using the app, it would very tedious in the sense that I have to scan each item. But I think if there’s an awareness of that and people start thinking about what they’re eating, then it could absolutely create a change.”

Teresa Morante Arona, a second-year geographic analysis student, believes there is a lack of conversation on food fraud.

Even though Morante Arona doesn’t walk into a supermarket looking to buy a product made in Canada, not knowing the farm something comes from concerns her.

“There is so much discussion right now about how animals are treated ethically, where our food is coming from, if it is genetically modified,” she explained. “Knowing where the farm is or what that farm is about when they’re growing their produce or raising their animals would definitely sway me into buying something a lot more than just hearing the country of origin.”

Morante Arona said she doesn’t have to shop for a family and because of that she wouldn’t mind spending the extra money knowing she is shopping locally. She tends to purchase produce that is in-season and Ontario-based.

“I am becoming more conscious on where I am getting my meat from,” Morante Arona added. “Meat is expensive and being a student, [it’s] kind of difficult to be like, ‘Oh, I’m going to be really selective and I only want the chickens that were raised in a field.’”

Good food can be expensive for students

Trevor McConnell, one of four founders and directors of Ryerson’s Food Innovation Hub, which helps entrepreneurs with food businesses, never experienced a situation where he was misled into eating something he didn’t intend to. He said the hub hasn’t had any companies coming to them asking about mitigating food fraud.

McConnell said there is a broken food system in general and food fraud doesn’t help in terms of sustainability, but he doesn’t know if people care.

He said having a DNA barcoding app would be a great step toward mitigating food fraud because it would give insight to people about what they’re eating.

“If this was to become a huge issue, and I don’t think it is, where meat was constantly being mislabeled and people were being misled into eating products that they weren’t comfortable eating like horse meat, then I think you would see a trend of people switching to vegetarianism,” he said. “But I don’t think food fraud is a major factor for people considering switching or people who have switched in the past.”

Leave a Reply