Like what you’re reading? This story is from our Accessibility Issue! Check out the other stories here. Want to see more? Of course you do.

By Annie Arnone

Meg Power zips up her jacket and puts on her gloves, listening to the humming sound of wind pound against the frosted window of her grandmother’s home.

She looks over at her grandmother sitting patiently next to her in a wheelchair, waiting for Power to dress her for the snowy weather—something she cannot do herself. She gently slips her arms through each coat sleeve and places a warm blanket over her legs.

It’s been hours since her grandmother had gotten out of bed and sat in her chair. She begins to slip off the seat. Her body often grows tired of being stationary, her muscles give in and she can no longer hold her in place.

Power looks down at her grandmother, who is finally dressed and ready to leave. She timidly asks Power for one last thing. “Make sure no one sees my underwear, please.”

PHOTO COURTESY OF ALEXA JOVANOVIC

The third-year professional communication student specializes in fashion studies, specifically disability fashion and accessibility.

Her first-year class, taught by Dr. Ben Barry— a Ryerson professor who teaches a first-year fashion course—dealt with topics in fashion such as diversity and inclusivity, as well as the concept of how disability intersects with art. That, coupled with the exposure she’s had to people with physical disabilities in her life, has inspired her to focus on adaptive and disability fashion.

According to a 2012 Statistics Canada study, about 15 per cent of people in Ontario live with disabilities and that number will only grow over time because of the aging population.

Despite conversations surrounding accessible housing, transportation and design being relatively common, accessibility in the fashion industry is not as prevalent. From physical to sensory disabilities, a large percentage of the population is unable to buy clothes from certain stores because of price and de- sign flaws that generalize certain disabilities.

Companies such as Ashley’s Adaptive Apparel and Adaptive Clothing from Debra Lynn exist in Canada, but the prices for people like Meg Power’s grandmother are far too high (an adaptive dress on the Debra Lynn website is $94, excluding shipping).

Currently, Power’s grandmother is on an oxygen tank and is living on the Ontario Dis- ability Support Program (ODSP). She cannot afford to buy clothing she feels comfortable in, let alone “beautiful” in. “It’s a huge effort to put on clothes for her, because she cannot afford adaptive clothing,” Power says.

Grabbing hold of the skin on my stomach between two fingers, I closed my eyes tightly as the nurse at Mount Sinai Hospital pressed a button against my flesh, inserting a needle into my body.

I held the cellphone-like device in my hand, connected to the needle in my stomach by a thin tube, and inserted it into my pocket, hoping that no one would see.

I’m a robot, I thought, as I stared down at my new insulin pump.

I was 16 years old when I was diagnosed with type-one diabetes—a disease that occurs when the pancreas can no longer produce insulin. I was skinny, tired, and my health was abysmal, but my main concern was the way my insulin pump looked on my body.

I continued to feel this way for a long time, fumbling as I tried to insert the device into my pocket—pulling my shirt over it constantly— until I found out about AnnaPS, a Swedish company that designs adaptive clothing for type-one diabetics who wear external devices like a pump.

The only problem is, it’s expensive.

A single women’s T-shirt on the AnnaPS website retails for €53.50, which converts to about $78, including shipping.

My idea of buying one of those shirts and washing it every other day was quickly disregarded by the people around me, who told me I had to be insane to pay that kind of money for one shirt. And they were right, so I continued with my daily shirt-tugging until I had finally given up and went onto syringe injections. I couldn’t take the way I looked anymore, and questioned my thought process around that.

Why can’t I wear something that makes me feel beautiful? It didn’t seem fair.

But in October 2016, my thought process was mirrored by IZ Collection—a Toronto-based adaptive clothing line that filed for bankruptcy. Owner Izzy Camilleri told the Toronto Star that the store was impossible to sustain and balancing prices based on their “locally made” product became too difficult.

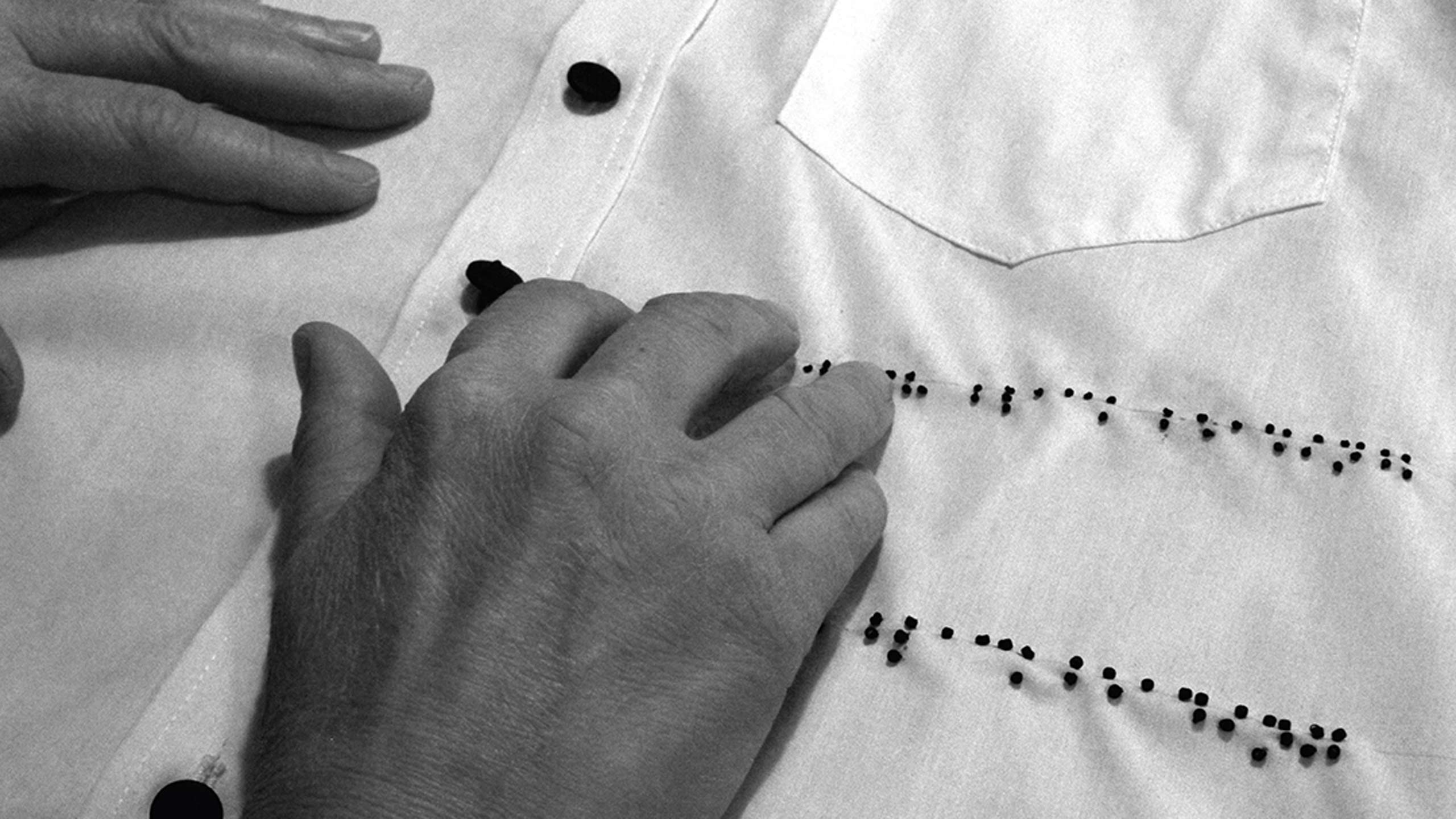

But a new collection, created by a recent Ryerson fashion design graduate, is giving people with disabilities new options to better customize their wardrobes. Alexa Jovanovic, 23, has specialized in adaptive braille clothing. She’s been working on her line, Braille, since her thesis project that she completed in her last year at Ryerson.

“The project was me working with seven blind individuals. Together we determined a better solution for the current problems they face getting dressed, as well as social stigmas they face,” she says. “I made the connection between the small size of beading you find on clothing, and thought ‘Why can’t beading have a function beyond its aesthetic value?’”

Jovanovic recalls meeting the group for her project—nervous about how she’d come across to them, not knowing much about braille. Her anxiety soon eased when the group began to bounce ideas around about what they hated about fashion—all coming to the same conclusion that braille tags are uncomfortable.

Often, visually impaired individuals purchase items with tags with braille descriptions that help differentiate clothing colours, which allows them to match their outfits. But Jovanovic realized that they were unanimously unliked due to their itchiness on the back of their neck. People who wish to avoid this will sometimes use different pins, which may not be aesthetically pleasing.

“I thought it was incredible that something like this didn’t already exist, to be honest,” says Jovanovic. “I created a removable clip, in addition to the braille design on the clothing, which simply listed the colour of the garment.”

Despite her late nights hand-sewing tiny beads to her designs, she thought about the fact that most people do not have the luxury of finding their own designer, and those that do can’t always afford it.

“Individuals with disabilities are often overlooked as consumers,” she says. “They’re generalized and the products that are available are extremely expensive, and not exactly reliable in terms of what each unique body is looking for. The alternative is people hiring their own designer. Which is obviously extremely costly.”

Power also says that the fashion industry is definitely taking steps to be more accessible, with companies such as IZ, and professors who advocate for adaptive wear like Barry. However, they have a long way to go.

According to Power, Ryerson should provide full classes or programs that deal with adaptive design, specifically.

“I think that’s something that Ryerson can really benefit from—some sort of integrated adaptive technology program,” says Power. “We have really cool things going on in FCAD, like Transmedia storytelling which is an event that discusses using modern resources to impact people’s lives for the better, so let’s expand on that.”

Power thinks about her grandmother, who fuels her passion for adaptive and inclusive design, and hopes that one day soon she’ll be able to feel beautiful and comfortable in her clothing.

“Access needs to be automatic. People need to want to help each other and get to know who they are—understanding their needs,” she says. “When we get to a point where there’s a strong enough community, where more than a handful of people work on these designs— just like they do in the fashion industry that doesn’t include the physically disabled—then there will be hope.”

Grabbing hold of the wheelchair, Power leads her grandmother out the door and into the cold. She knows by the look on her face that this is hard for her—she isn’t comfortable, she wants to be warm—she wants to look her best. A similar sentiment that I share.

Wendy Black

Good Morning

I was wondering why silvert’s was not suggested we have adaptive dresses for 42 and tops starting at 22?

Thanks so much

Izzy Camilleri

I’m just seeing this article now, and wanted to let you know that the IZ Collection did not file for bankruptcy, but decided to close operations. There was and is no bankruptcy. It was an internal decision to closed based on many factors which included the cost of producing locally which you explain in the article. If you can make the correction in the article, omitting that the company filed for bankruptcy, as that fact is incorrect, that would be greatly appreciated.

Kind regards,

Izzy Camilleri