By Madi Wong

When professor Sarah Henstra was in university,she found herself stuck in the middle of two opposing sides: a wild partier and a heated theoretical debater. Which ultimately led Henstra to question her values, much like the narrator in her novel.

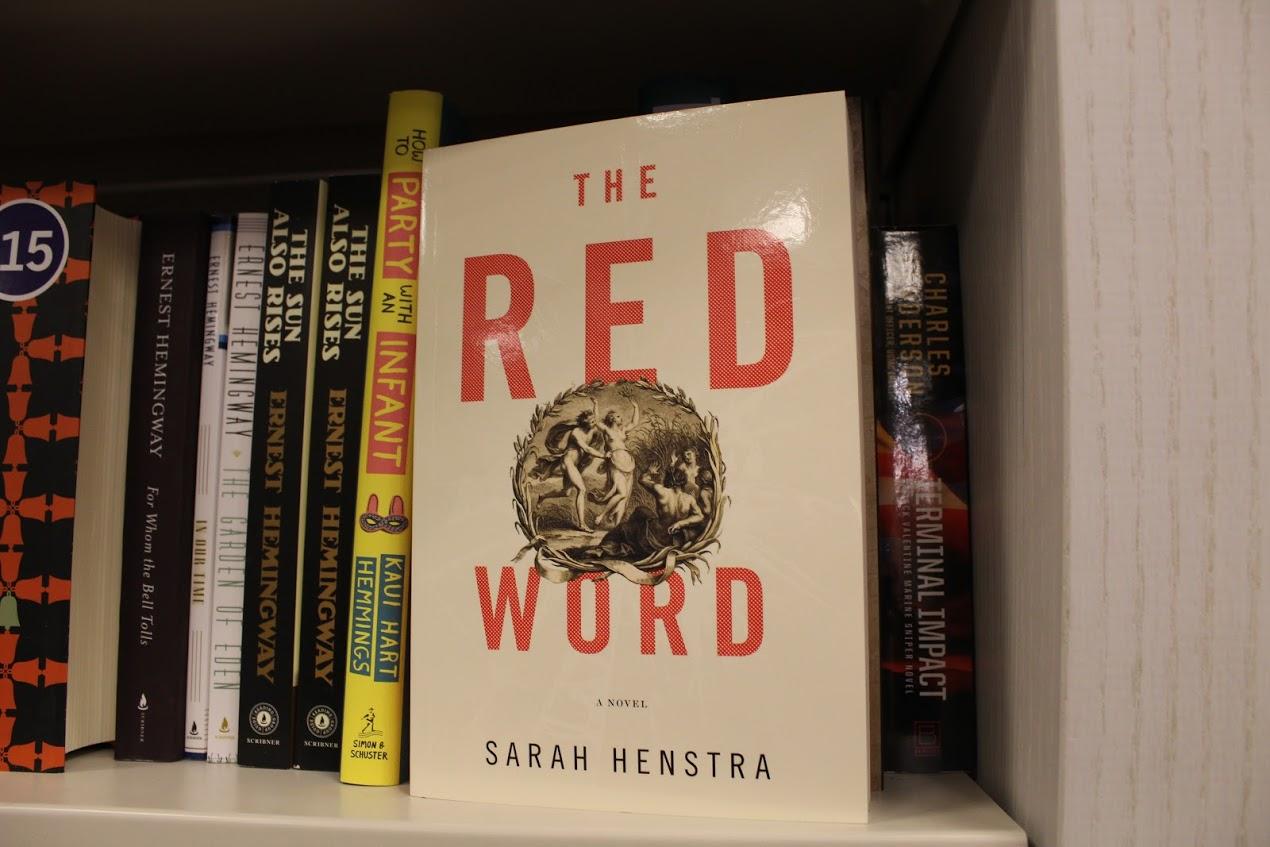

The Red Word—Henstra’s novel was created based on her own experience as an undergraduate in the 1990s. It follows the story of undergraduate feminist students striving to ban fraternity houses off campus for their sexist frat culture. The girls’ burning passion came from their charismatic professor, their own realizations about the toxicity of rape culture on campus.

“I felt like a bit of a fraud in both camps because I had a boyfriend or been out drinking late with the boys. And then, on the other hand, I was raising potluck with all the feminist students. I was interested to write about that experience of feeling like an observer,” Henstra explains.

The feminist students in the novel believe that frats should be banned due to their sexist, misogynistic interests at the expense of women. The evidence they use is the typical bad boy behaviour and objection of women within those households and on campus.

When comparing her undergraduate experiences to her observations of students today, Henstra says that young people seem to be more articulate about their own rights, sexual autonomy and not being subjected to sexual violence. As well as the rise of the conversation being more publicly held regarding hard and confusing topics like rape culture.

“It was hard and confusing to talk about it. We had the terms like ‘date rape’ but they didn’t seem to cover certain kinds of drunken party hookups. It was hard to talk about it when you felt like something was wrong, since the conversation was not being held publicly, so that has definitely changed,” Henstra said.

The Red Word by Sarah Henstra mixes in feminist theory and mythology to portray the story of young undergraduate female students who tackle rape culture on campus. (Photo: Madi Wong)

Henstra was excited to talk about the ideas she had learned in school, such as Greek, classical mythology and third-wave feminism. Coincidentally, these ideas were all rolled into the course, “Women and Myth,” that the professor in her novel teaches.

She portrays these ideas mainly through the narrator, who is one of the female students, reflecting on her life and experiences from 15 years in the future.

“The narrator sees things in terms of epic stakes, like life and death. She turns to Greek myth as an understanding of what she went through, such as the Iliad,” Henstra said. She also writes some of her dialogue like choruses from Greek poems, such as the Iliad. Choruses were a group of men or women in Greek drama, used to designate sound and meaning.

Henstra says regularity has helped her avoid writer’s block and refers to her writing as a practice because much like yoga or running, she has to do it regularly in order to wrestle with ideas and get some word count.

“I keep my writing practice contained as part of my week … I also have a network of writing buddies where we show up at a café and work for a couple of hours. And stopping each other from distractions. It’s like having a running friend to have that bit of accountability to drop what you’re doing and go,” Henstra said.

“I ask myself all the time, ‘Where’s the juice going to come from?’ because [as a writer] and running around your daily life, you need an extra something to fuel the writing,” Henstra said.

Henstra finds inspiration from books, great works of literature, being outdoors and visual art. She sometimes writes in the art gallery where she is surrounded by random pieces that ultimately feeds into her writing.

As for her favourite part about writing, Henstra says that it’s the secret and private feeling of when nobody knows what she is working on.

“I see the word count accumulating day by day, and month by month and I know that I’m sitting on a novel. When it starts to get the point when it’s done, I’ve made this whole thing and nobody has read it. Or criticized it. And nobody has asked me to change it. And it feels perfect! It’s like I’ve created a whole world,” Henstra said.

Leave a Reply