THE TABLETOP ROLE-PLAYING GAME IS MORE THAN JUST A FRIDAY NIGHT WITH FRIENDS. HERE’S HOW IT HELPS INDIVIDUALS DISCOVER THEIR IDENTITY THROUGH WHO THEY ARE, WHO THEY’RE NOT AND WHO THEY CAN BE

Words by Nathaniel Crouch

In my first year of university, I gathered five of my closest friends on a cloudy Saturday morning. We sat around my kitchen table, surrounded by maps, dice and character sheets. My friends listened closely as I described the fictional world the story would be set in: the island continent of Terramorn. Their main quest for the “campaign”—the overarching storyline that leads players through game—was to head north on the island to aid the leader of the nation. The “party”—a group of players working together—was made up of a half-orc faithful to a sun god, a dashing elf cloaked in shadows, two magic users and a shapeshifting gnome. Each had their own flaws, personality traits and least favourite food. It was each of my friends’ first times playing the tabletop roleplaying game known as Dungeons and Dragons (D&D). It took four hours of the most chaotic gameplay I’ve ever witnessed before everyone caught the rhythm of their characters.

It was also my first time taking on the role of Dungeon Master (DM), whose responsibility is to craft the world and run the players through social encounters and battles. As the game goes on, players choose the action they’d like to take by rolling a 20-sided die, whether that be investigating a crime scene, smacking a monster with their weapon or haggling with a local merchant for a discount. Both the DM and how high of a number they roll determine whether their chosen move that turn is successful.

In a moment that surprised all of us, the half-orc, named Solomon, a burly and bearded holy knight, began flirting with every male with large forearms. Weeks later, the holy knight was awkwardly commenting on the girth of the arms of the shirtless, muscular airship captain. We didn’t think much of it, since flirting with captains is nothing new in D&D. But then, Solomon’s player turned to us in real life and said: “Man, I’d sure like to have him here in real life. Get it?” We didn’t get it. “Because I’m gay.” It was as if before he did in real life, he had come out to us in the game.

Playing D&D makes for a fun Friday night with your friends—campaigns take place throughout multiple sessions, oftentimes spanning weeks, months or even years. The immersive aspect of the game allows players to choose every element of their character, from their sex and gender, what they believe in, to what their strengths and weaknesses are. Once players choose their character traits, they may be able to draw out their characters, or even purchase and paint figurines that resemble the characters they choose—but otherwise, you don’t ever really see your character. D&D is a game where you use your own imagination.

The options are limitless, and some players find that this serves as a form of self-exploration: D&D allows us to escape ourselves through the ability to create any character imaginable, that you get to become for hours at a time.

A 2014 research paper conducted by Pamela Livingstone, a graduate of Ryerson’s digital media masters program, discusses why a D&D character often shares similar traits to its player. Character creation involves a combination of who a player is and who they want to be, based on their community and social norms, according to the paper.

Some Ryerson students find ways of embracing or escaping their own identities through this aspect of D&D. What they learn about themselves while playing the game can be used in their real lives. Solomon and his player coming out wasn’t the only roll for self-exploration. My other friends found themselves exploring new sides of themselves, such as the gnome staying in an androgynous animal form. I personally found myself exploring my feminine side through different characters. I was both feminine and powerful and feminine and patient.

Victoria Menerios has been playing D&D for five months. She plays as a halfling rogue named Salem—a plump lad with a bulbous face, as she describes him. Salem stands at about three feet tall, with the classic hooded, leather-clad thief look. The halfling is a stout and strong male character—something she chooses to be in order to escape the struggle of everyday womanhood.

Menerios happens to play with a party full of men. Male characters are generally more relatable to Menerios. “I am not a very feminine person—the male characters dress more like me and act more like me.” For this reason, it’s easier for her to find a community in male form in the game. “It creates a belonging,” she says. “There is nothing different about everyone, and people don’t look at you like a girl, and that you stick out, or think you shouldn’t be there.”

Similar to Salem, Menerios is on the shorter side. Reaching or lifting things are hard for her in real life, so she uses her halfling rogue to compensate for the capabilities she doesn’t have.

Not all players need a completely accurate version of themselves, Livingstone says. “Some players decide to build an idealized version of some aspect of their life they wish could be different. Many players will choose a character that they could not be in their real life.”

“I am hoping these norms will be erased in the future,” she says. Slowly, those norms are disappearing within game culture itself. In 2014, D&D released the fifth edition of its rulebook, including various updates to character creation, which encourage more sex and gender fluidity. “You don’t need to be confined to binary notions of sex and gender,” it reads. “You could also play a female character who presents herself as a man, a man who feels trapped in a female body, or a bearded female dwarf who hates being mistaken for a male. Likewise, your character’s sexual orientation is for you to decide.”

The gender identity of a player’s character doesn’t affect any of their in-game strengths and weaknesses, just the roleplaying. According a 2015 study that explores how privilege and power shape racial and gender identities in the tabletop games, there has been an increase in female representation. Example characters drawn in D&D books who are women increased from 22 per cent of all characters in the first edition in 1971 to 55 per cent in 5th edition. Those characters also no longer have sexualizing outfits and armour.

Menerios has seen more fluidity, equity and equality in the campaigns she plays. “With monsters, gender doesn’t even matter. Not mentioning a gender, it doesn’t matter in D&D. You see a lot of characters with good armour and swords, and then you see characters that are a little more reserved, small or skinny. Things are changing, because the people playing them are changing. Things that might not conform to society will bleed into the books.”

“For now, it’s nice to be a tough guy, be able to save the party, be strong and be quick.”

Salem is also learning what he can and can’t do. Although he is strong and capable—he is still small and isn’t able to move a boulder or fight a monster one-on-one. Salem, for this reason, represents two things at once to Menerios: something she is and something she isn’t.

George Swede, a Ryerson professor who specializes in the psychology of art and creativity, says character creation isn’t just affected by what we see in ourselves, but also what we believe others see in us. He adds that whether or not we’re aware of it, our actions in D&D are prompted by unconscious needs and desires. “We think it is just chance or accident, but it’s already been determined,” he says.

Livingstone’s study states that just as in real life, making a character creates a hybrid of identities. “It’s the representation of both you and another identity you have taken on instead of having two separate personalities, you have one that is meshed together,” she says.

“It’s similar to how I feel because I’m a pretty short person. When I have moments where people notice how small I am, I find it annoying because people make short jokes,” Menerios says. “But, with Salem it is kind of an advantage. It is nice that it is not looked down upon and it is something needed in a party.”

One session, Joy Patterson and her party members finally caught the villain they’d been hunting for a while. They were deciding whether they should kill him, so they put it to a vote—Patterson was the last to to cast her ballot. All she could say was, “Oh, I don’t know.” This was her first-ever D&D character: a passive paladin.

She realized her indifference doesn’t allow her to get as invested in quests as other players are. Patterson’s fellow players would come up with large-scale plans to overcome massive obstacles in game, but she wouldn’t give nearly as much insight or aid. “It got almost impossible for me to do anything.” Her personality had bled through to her character—she realized she had to work on her passivity in real life.

When Patterson shifted characters to an unstable druid, she realized a new problem as she tried to be more invested in the scenarios the game presented her with: even as a new character with a very high charisma—which would typically mean they’re good talkers and very persuasive—Patterson would still avoid talking to others a much as possible. Even when in-game conversations happened, she says they’d go badly due to her real-life awkwardness. “Even though these characters have high charisma, I’m just terrible at it.”

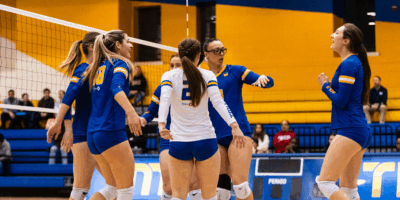

The third-year new media student started playing D&D through the Association of Ryerson Roleplayers and Gamers (ARRG). The group runs multiple campaigns by organizing players and DMs across campus for semester long games, there isn’t a skill level required. The group works as an intro to D&D and players can request to be in campaigns alongside their friends, helping people get over those beginning anxieties.

D&D evolves as its popularity fluctuates and as the people who play and influence it come from newer generations. It’s no longer the inexplicable thing the guy from your local game shop plays in his basement. According to BookNet Canada, a non-profit organization that develops technology in the Canadian book industry, sales for the D&D starter set books have been slowly increasing over the past few years, going from around 15,000 units sold in 2013 to more than 90,000 units sold in 2017. More notably, between 2016 and 2017, units sold increased by 95 per cent. As its popularity grows, self-exploration can too. But it doesn’t always have to be something as inherent to your identity as sex and gender—for some, it’s something as small as a social skill.

Patterson is still exploring and improving—she notes how she’s getting better in D&D’s social interactions. In the last five months of playing as her druid, she’s avoiding confrontation less and less—both in-game and in real life. If something is bothering her, or there’s a problem, she confronts the problem. “I’ll actually deal with it.”

As players move throughout the campaign, they come into contact with other citizens of the world and learn more about the game’s narrative, which gives their characters more meaning within the context of the game itself, Livingstone says.

I gathered my friends around my kitchen table in the last week of my first year. Eight months later, our campaign was coming to a close. New responsibilities meant weekly meetings would no longer be possible. Before we started playing, I took time in my room to gather myself, and a wave of sadness came over me—I didn’t want it to end; not having a constant meeting with my closest friends hurt. I had made a few discoveries about myself as well.

Playing every character from an evil dragon to other players’ love interests, I experienced adoration for a variety of characters. I realized the traits I considered attractive had nothing to do with appearances or gender—that was when I cemented my bisexuality.

We closed off our character stories. The holy knight retired to a small church. The dashing elf started a school to train youngsters in the art of stealth. The two magical individuals started a farm. And the gnome, who remained in her androgynous animal form, returned to the forest of her youth.

Leave a Reply