By Julia Mastroianni

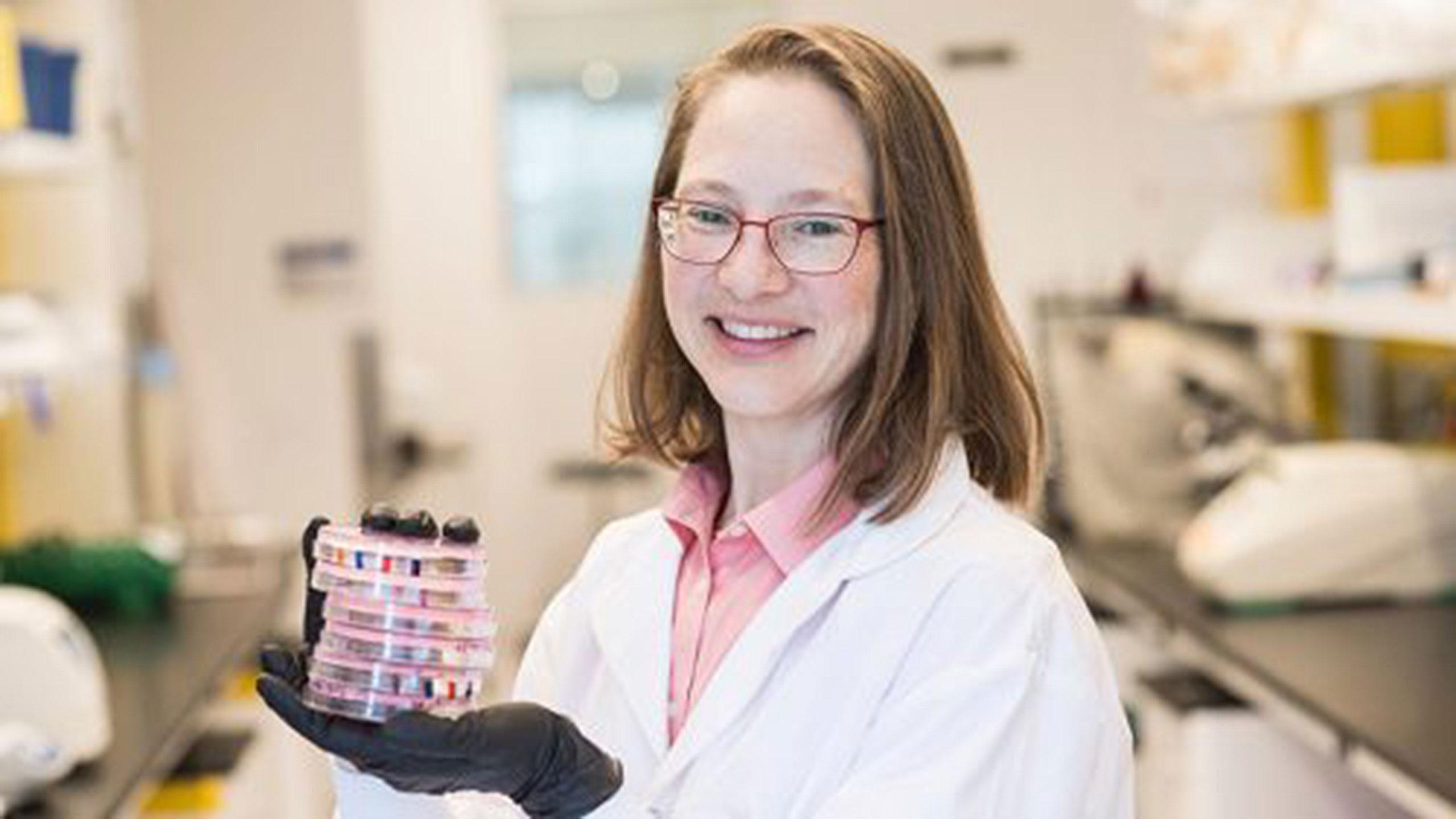

Many biologists interested in drug treatment to save lives spend their time watching out for death. But Ryerson biology professor Dr. Sarah Sabatinos is also interested in the survivors.

“Sometimes in cancer, you give the drug initially and then the cells mutate, they acquire resistance and then they come back and they can’t be treated,” Sabatinos said. She’s part of a collaborative project with RTA professor Dr. Ali Mazalek on chemotherapy drug treatment. They’re trying to determine which cells survive, why, and how to ultimately prevent them from developing that resistance.

Before coming to Ryerson in 2015, Sabatinos had been researching for years using yeast. She was researching replication forks (the area where DNA replicates) in yeast, along with fork collapse, the name for the process in which mutations often occur.

When Sabatinos met Mazalek, she asked if Mazalek would work with her on her research to visualize the data. Mazalek specializes in finding ways to involve other senses to understand data. This was instrumental to Sabatinos, who was working with thousands of strands of DNA.

“You really have to challenge your preconceptions of what matters in the sense of data; why is this important?”

Mazalek created an interactive tabletop and a multi-touch wall display so “users can grab bits of data and look at the data set, and then pick out bits of them that are then visualized on the large wall display in front of them,” she said.

The software is being used by other researchers to interact with the data. “This lets them both physically manipulate the data and also share it with each other to build a kind of shared mental model together,” Mazalek said.

For this project, Mazalek’s designs helped Sabatinos analyze the data by comparing different chromatin and fibers through laying them out visually across large wall screens and tabletop screens. “Humans are visual-spatial beings, we tend to think by laying things out and spotting patterns in them,” she said.

At the same time, Sabatinos spoke to one of her grad students who was interested in working on something “clinically relevant.” She happened to have yeast strains with transgenes—genes that altered the strands to respond like human cells to drugs—in the lab, along with a drug used frequently in treatment for pancreatic cancer. Sabatinos learned from a pancreatic cancer oncologist that they don’t know ahead of time how a tumor will respond to the drug. Not only does the drug not work on some tumors, but when it does, the tumor may eventually develop a resistance to the drug.

And so her research took on a new twist: determining which cells are sensitive to the drug, and which cells develop resistance. “What are the characteristics of those ones that come back? And then is there a way that we can prevent that, either by using a different drug or different timing?” Sabatinos said.

It’s a delicate balance between hitting the cell when it’s at the point of DNA replication, without causing more mutation

She also explained that though their research is directly related to cancer treatment, it would take a collaboration with clinical oncologists to translate the research into actual changes in treatment.

“That’s one of the things Ali [Mazalek] and I are interested in, is how do we bridge that gap? Can we use the technologies that she develops to understand how to translate that?”

Mazalek’s involvement in this project means that there is more focus on that translation than is normally the case for scientific research. Instead of leaving the data in scientific jargon or complex numbers, Mazalek has worked with Sabatinos to represent the research in engaging visuals.

Sabatinos said this collaboration between the scientific and the creative has impacted the way she approaches her work. “You really have to challenge your preconceptions of what matters in the sense of data; why is this important?” she said.” And if I can argue effectively that [the data] is useful, that actually makes my work better because I am thinking more clearly about it.”

Though her main research goal is to find out more about the timeline between initial sensitivity to a drug and subsequent resistance, Sabatinos also explained that there is a paradox they have to be careful of in their work.

The drug affects the replication instability of cells, meaning that if the drug doesn’t kill everything, it starts to prime the tumour or cell’s system for additional change.

“Humans are visual-spatial beings, we tend to think by laying things out and spotting patterns in them”

Sabatinos explained replication instability is so tricky because it is what promotes mutation, but it is also what chemotherapy takes advantage of to kill unstable cells.

She said chemotherapy is one of the only treatments that works for pancreatic cancer right now, and so it’s a delicate balance between hitting the cell when it’s at the point of DNA replication, without causing more mutation. “So this is what we’re trying to understand, where is that point [of balance], and does it look the same, and can we predict what the outcome is?”

Sabatinos hopes this project can eventually be transferred over into mammalian cells to determine whether the research is applicable outside of yeast cells. They’ll also be collaborating with Dr. Susan Forsberg, a researcher in California, which Sabatinos said is a great asset considering all their yeast research and data.

She emphasized that it’s all about finding the right people who have the skills and want to work with you, and Forsberg and Mazalek were exactly that. “That’s a really neat thing, that the people with the right skills and data and tools to do this job just happen to be three women.”

Leave a Reply