By Dhriti Gupta and Giulia Fiaoni

G rowing up, Aly Atallah wasn’t allowed to open the windows of his house in Cairo, Egypt between the hours of 8 a.m. and 11 p.m. This was to prevent the thick smog of air pollution from getting into the house. This wasn’t the only household restriction—his mother wouldn’t let him eat candy if she didn’t know how it was packaged and he wasn’t supposed to wear rubber flip flops in case the material contained chemicals.

After months of feeling depressed and afraid of air pollution in Cairo, Atallah’s mother told him they were moving away within the week. She was taking him to live in Alexandria, a city on the coast of Egypt.

Fast forward to university, Atallah’s mom chose Canada for his education because of lower pollution levels. Their lives revolved around things to avoid the dangers of air pollution. Now in his second year of marketing at Ryerson, Atallah notices that his peers show an overall lack of action on pollution issues.

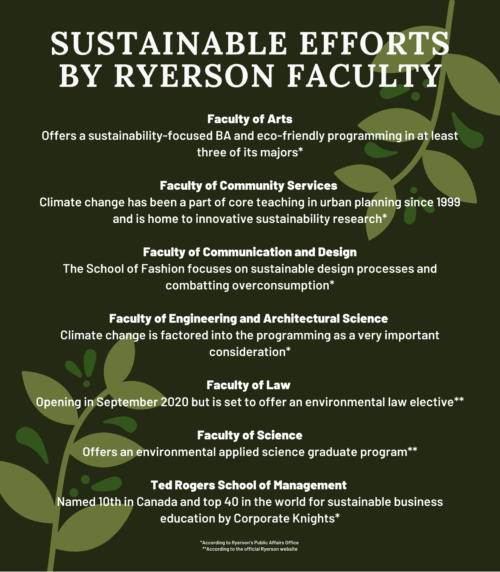

With increased awareness around the climate crisis, more universities are implementing a sustainable lens in education. Environmental Careers Organization of Canada (ECO Canada) lists 33 environmental post-secondary programs that are accredited. Ryerson’s environmental studies and urban sustainability program is not accredited according to their standard. But students want to see climate-related content across all disciplines.

At Ryerson, some professors have made it their mission to include environmental content in their curricula. Students say they’re already aware of their career’s environmental footprint and want to see this reflected in more of their courses.

“When you pay for your education, it should be education that benefits you for your life and society as a whole,” says Deborah de Lange, a professor of global management studies in the Ted Rogers School of Management (TRSM). “That’s why it’s very important that we learn about climate change.”

Atallah finds that his courses’ case studies focus on technological advancements in business, but he feels sustainability is just as important to consider. “Why don’t we talk about cases happening now, about plastic producers, about rubber producers and how people who are cutting plastic and rubber out of their lives affect the business world?”

S ustainability has been a driving force for de Lange ever since she saw a solar cell on a field trip to the Kortright Centre for Conservation as a little girl. She carried that curiosity forward into her career and was surprised to find that her PhD program included nothing about climate change or sustainability.

When she became a professor in the United States, de Lange got readily involved with the Organizations and Natural Environment Division at the Academy of Management. She essentially took on an informal second PhD, conducting her own independent research into sustainable development.

De Lange researches how sustainability plays into corporate strategy, drawing upon the real-life example of energy storage and clean technology. In one of her courses, she explores the challenges of being a sustainable company in an international context.

She focuses on structures necessary for global expansion to take place within a world facing climate change and rapid technological change.

Because professors teach what they learned in their PhD, de Lange recognizes that not everyone has the extra time or capacity to adapt their course to have a sustainability lens.

“If our research fields are narrow, which tend to be, and [are] not multi-disciplinary, they may not encompass sustainable development.”

But de Lange says there are other ways to make climate change education more widely available to students, such as inviting experts to host research seminars on sustainability. Ryerson has a set of research seminars on ethics, but they don’t currently touch upon climate change.

To diversify content, de Lange encourages universities to hire more professors with sustainable backgrounds to tenure track positions. She stresses these solutions are only possible when the administrative leadership at universities make climate change education a priority.

“I think when you talk to people, everybody is agreeing with the importance of doing something about climate change. But we need [an] action plan,” says Ryerson president Mohamed Lachemi. “As a university, we foster an environment in which we can debate this issue and come up with some recommendations on how we can do a better job.”

According to Ryerson’s Office of Public Affairs, several faculties at Ryerson prioritize climate change within their programming and core teaching. “Our students learn how climate change not only impacts their future work but how it’s impacted the work of past engineers, architects and building scientists.” In the Faculty of Community Services, sustainability has been a part of core teaching within the School of Urban and Regional Planning since 1999, including studies in green infrastructure, sustainable water practices and food security.

W ithin the first few weeks of Kareen Ng pursuing a degree in fashion, she found out that her dream industry was the second most wasteful industry in existence.

Sitting in her first introduction to fashion course, Ng learned all about sweatshops and the labour that goes into fast fashion. Ng grew up in an eco-friendly home where her family brought reusable containers to restaurants to take home leftover food. She is passionate about reducing her carbon footprint.

But now she’s realized that her passion for living an eco-friendly life stands in direct contrast to her dream job in the fashion industry. She’s considered finding a career that has less of an impact on the environment but feels that while she’s in the fashion industry, she might as well try to make a difference.

Currently, in the second year of her degree, she’s already been faced with a variety of challenges. Deciding between affordable polyester that is not biodegradable and other pricey but more sustainable textiles has been a particular point of frustration. The program never funds textile costs required for projects, Ng says, so many students seek out cheaper and less sustainable alternatives, like polyester.

In a statement to The Eye, Ryerson said the School of Fashion has introduced concepts of zero waste pattern drafting—a practice to eliminate waste during a project’s drafting phase. They’ve also implemented sustainable design and manufacturing processes and combatting overconsumption into their curriculum. They did not respond to a request for comment on Ng’s specific concerns in time for publication.

Ng has visited numerous fabric stores across the city in an attempt to find the most affordable option for her projects.“What kind of blend is this? How much is it going to cost me?” she asks while she shops. “It just overwhelms [me] to the point where I can’t even think about sustainability.”

Ng tries to avoid waste by reusing materials, by turning scrap fabric into hair scrunchies and trading clothes with friends to create different looks.

Sanjay Sharma is the dean of the Grossman School of Business at the University of Vermont and is responsible for the reinvention of the school’s world-renowned Master of Business Administration (MBA) program. It is ranked number one in the United States and number five globally.

Sharma emphasized the need to “totally disrupt” the original program instead of just modifying it. “What a lot of programs do is they take the same old ‘MBA horse’ and they put a saddlebag of sustainability on it, but it’s the same old MBA horse unchanged.”

Instead of courses, the program has modules. Sustainability was integrated into each module from the beginning, instead of it being an afterthought. All of the cases are about sustainability.

“These are students coming from very different backgrounds. The only thing [they have] in common is that they are committed to addressing sustainability challenges.”

As former dean, Julia Christensen Hughes decided to make sustainability a part of the vision at the Gordon S. Lang School of Business and Economics at the University of Guelph. Over the course of a year, she found by facilitating several focus groups within the university, as well as amongst employers, that people believed business could and should be a positive force for change in the world.

Despite having been met with some external pushback, she feels that current guidelines from organizations like the United Nations give schools seeking sustainable approaches a solid place to start. “Universities as a whole are really being strongly encouraged to get in line with the UN sustainable development goals for 2030,” she says.

A t its core, de Lange stresses that climate change education is essential in universities as a part of their mandate to produce critical thinkers.

“Tomorrow will be something else if we don’t start educating students properly, not for jobs, but for their lives, for society and for the earth itself.”

Leave a Reply