“Every time I burnt myself out, the positive outcomes of my actions reignited the flame”

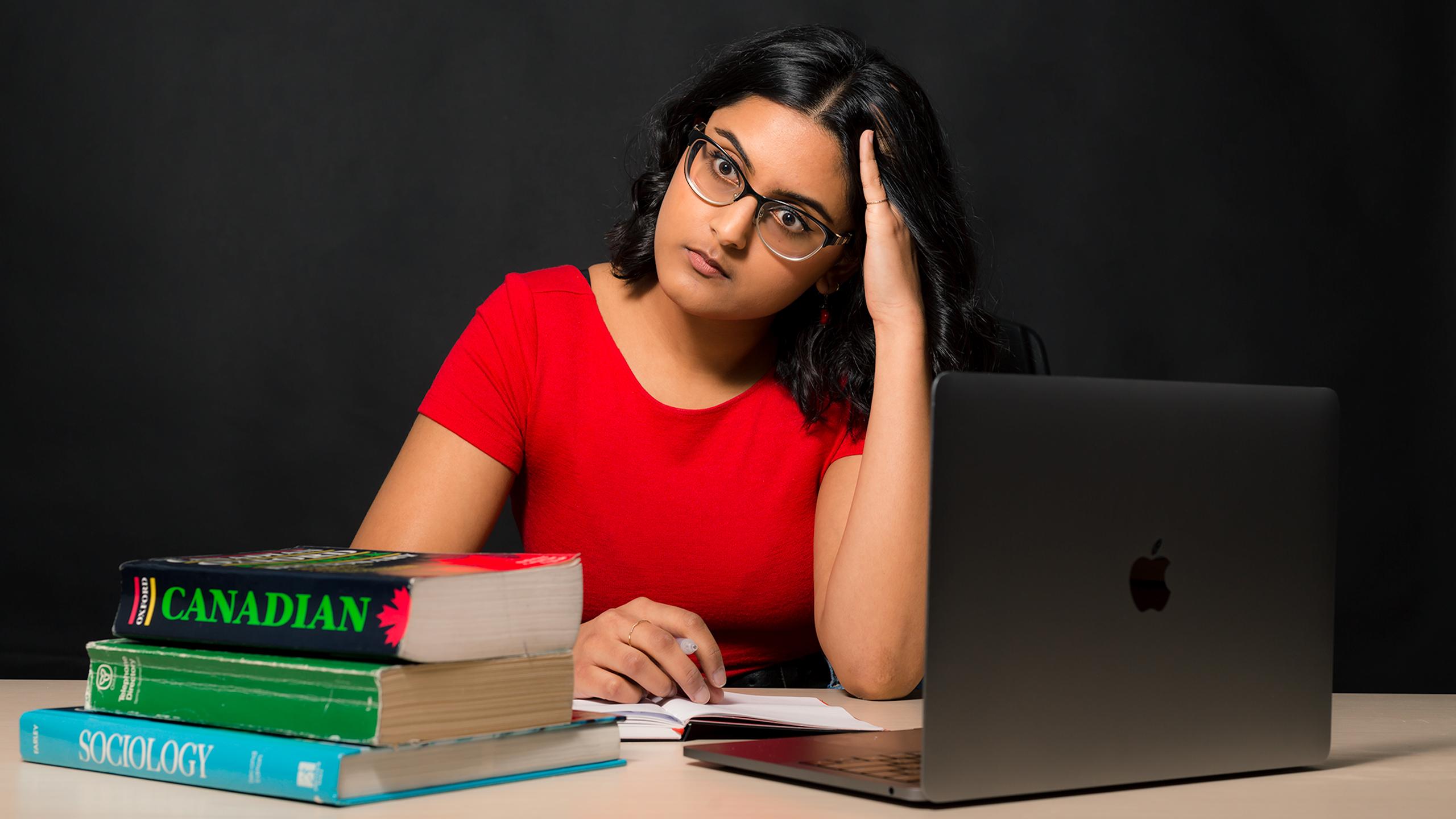

Editorial by Dhriti Gupta

Photo by Jimmy Kwan

I‘VE NEVER known how to set boundaries for myself. And up until university, I never wanted to either.

At 9 p.m. in my high school cafeteria, I hunched over a Biology textbook as the janitor rumbled by while mopping the floor, probably judging me. At home, when a notification from a friend in trouble flashed across my lock screen at 3 a.m., I would call them to whisper words of comfort into my phone—while secretly calculating how many hours of sleep I could get before my exam the next morning.

These days, I click the offline Google Docs tab I saved from earlier, sleepily editing drafts of articles on my train ride home.

No matter what was asked of me, my answer was always yes. But why would it be anything else, when after every instance I pushed myself to the brink, I’ve been rewarded? Whether it was the proud, beaming smile of a teacher or a heartfelt text from a friend, every time I burnt myself out, the positive outcomes of my actions reignited the flame.

I had the formula down—never say no, work till you drop and make sure you’re doing the most; more than others, and more than what’s expected of you. If I did it right, I got the external validation I built my entire self-worth around. And if I did it wrong? Well, it made it that much easier to know where I could still afford to demand more from myself.

Because of this, it’s easy for me to identify as an overachiever—a term that’s easily one of my top 10 most insufferable humble brags (among, “Oh, it’s so hard to have naturally curly hair,” and “I just have to organize everything”). My relationship with burnout has always been reactive—I really believed it to be an inevitable side effect of success, but now I realize how it was instead a side effect of the environment I grew up in.

I didn’t grow up like this by myself. In high school, my peers would compete for the longest lists of executive club positions to put on their university applications. Now, in my second year of journalism, my fellow student journalists and I discuss how tempting it is to accept an unpaid internship. Even in our current situation, in the midst of a Literal Global Pandemic, rise and grind Twitter continues to shame people for prioritizing their mental health when they could be using their precious free time to cultivate an idea for a new startup or finish their manuscript.

The thing is, not everyone is hustling out of passion. For many, hustling is not a life choice, but a necessity to support themselves and those close to them. It’s a vicious cycle for young people who have to hustle for a good quality of life, and then are too quickly drained by it, but continue to not have a choice.

On top of that, we are constantly being fed the idea that if we work hard enough, it doesn’t matter what we go through to reach success or survival. I see headlines boasting “Three Simple Techniques To Quickly Fix Employee Burnout” and “The Secret to (Almost) Infinite Energy,” but almost nothing on how and why we are expected to take part in work that’s doomed to drain us.

The Hustle Issue aims to answer those questions. What if you can’t finish school? What if you don’t want to be exhausted by the only thing you’ve ever wanted to do? What if you can’t support your friend right now? The conversation around hustle culture in our society needs to change, not the people trapped within it. It’s unrealistic to think the world will stop for our mental, physical and emotional wellbeing, but maybe we can learn where and how to draw the line ourselves.

Yes, we all really be out here, but when did it stop being fun?

Charmaine

The Biggest Mood

Valentina Caballero

This is so relatable and very true

Kirsten Anderson

Wonderful writing, Dhriti. Important and honest insight. Perhaps the pandemic will give us a chance to reevaluate what we value. I’m wearing the proud, beaming smile of your grade four teacher.