Content warning: This article discusses sexual violence.

By Uhanthaen Ravilojan

I was on Gould Street at 10 p.m. when a man called me beautiful and asked to take me home.

I was scared, but knew I shouldn’t be. I was told men don’t get scared—they get angry. I told him to fuck off. He crossed the street, stalking me from afar. I ran into the Engineering Building and asked for help. A student in the building advised me to call Ryerson security. After I thanked him, he wished me luck, laughing. “Don’t get raped!” he said. I was able to use the WalkSafe program to get home unharmed.

When I told my brother about the experience, he told me to “get buff” so people wouldn’t mess with me.

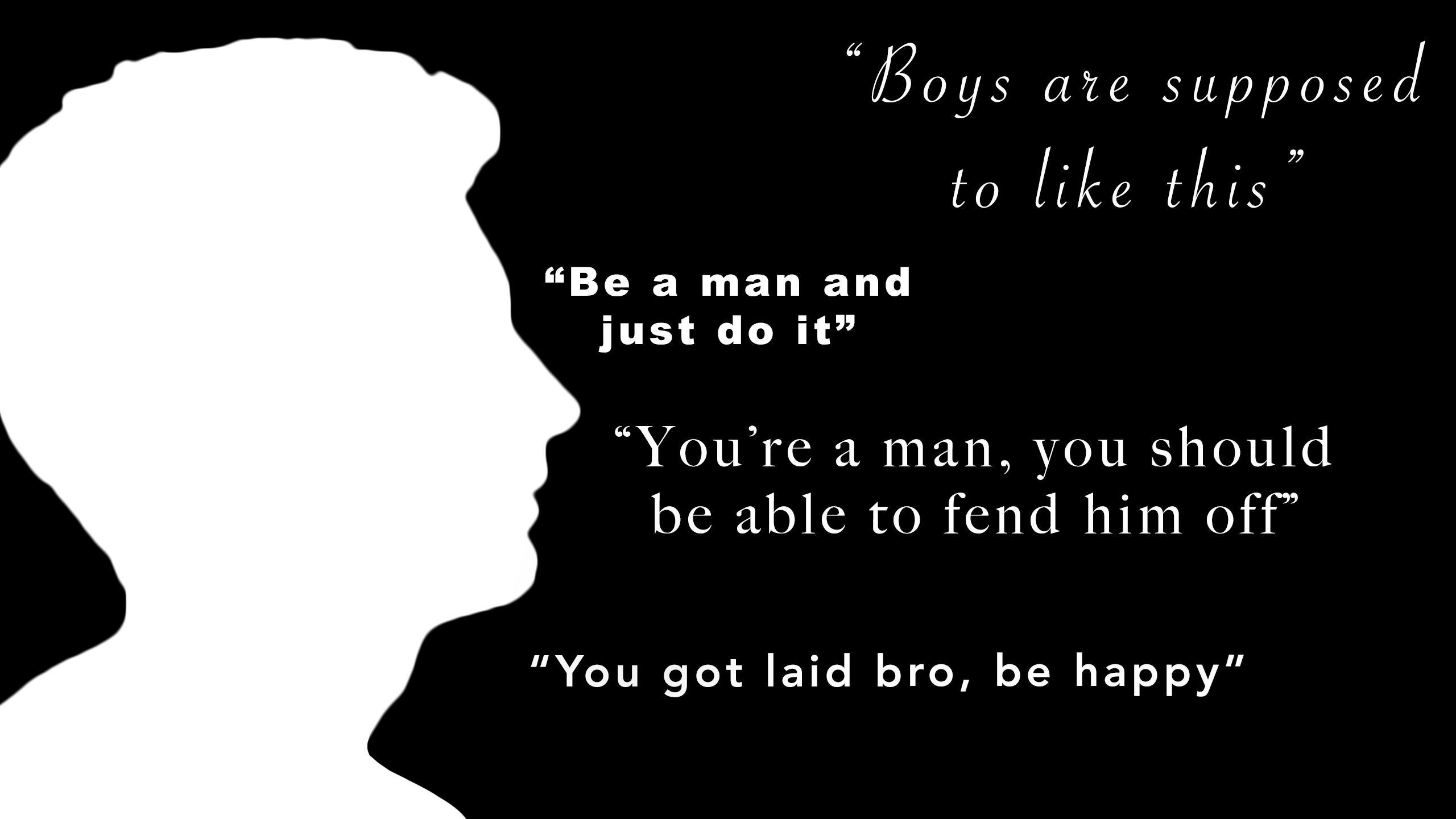

His reaction surprised me, but shouldn’t have. These are typical responses to men being harassed.

“There are unrealistic expectations placed on men and boys to always be in control,” says Kelly Prevett, a sexual violence specialist from Consent Comes First. “Perceptions of who a ‘victim’ is or how they should act are reflections of the association between victimhood and weakness, and are reflective of the internalized misogyny we all carry with us.”

Being objectified felt foreign. Since sexual violence disproportionately affects women—90 per cent of all rape victims are female, according to the non-profit Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network—I never expected to have to deal with it myself. In his book Psychotherapy with Male Survivors of Sexual Abuse: The Invisible Men, Alan Corbett, Chair of the Training Committee of the Institute of Psychotherapy and Disability, says that masculinity pressures men to act tough and strong, making the feelings common to victims of sexual violence and harassment—such as powerlessness—inaccessible to male survivors. “Victimhood” and how it relates to powerlessness isn’t in most mens’ vocabulary.

When I turned 22, I found myself being harassed more often. While training me for a new job, my trainer frequently called me handsome and forbade me from yawning because he found it “attractive” and thus distracting. Another time, I was riding the TTC when a man put his hand on my shoulder, said he loved me and called me beautiful.

It baffled me. Why did this keep happening? What made someone get harassed? Was it because they were good-looking? I didn’t consider myself attractive, and even if I did, why hadn’t my better-looking friends ever spoke of this? Was I just an easy target? Was it because I looked weak and effeminate? Was this my fault? I found myself buying into almost every misconception about sexual violence.

I was scared, but knew I shouldn’t be. I was told men don’t get scared—they get angry.

Prevett says that one in six men will experience sexual harassment or violence in their lifetime. The non-profit organization 1in6, which aims to raise awareness about male sexual violence, says the actual number may be much higher as the well known stat doesn’t include experiences without physical contact, such as mine.

According to Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network, male college-aged students are 78 per cent more likely to be raped or sexually assaulted than non-students of the same age. For male undergraduate students, 5.4 per cent have experienced rape or sexual assault through physical force, violence or incapacitation. For male graduate and professional students, the rate is 2.2 per cent.

In June 2019, I was studying on campus when I met Takeshi*. He asked me where the washroom was, complimented my appearance, and when I helped him, suggested I come in with him next time.

After that, I ran into him on campus frequently. He always talked about my body, once even complimenting the chest hair visible through my button-up shirt. I didn’t know how to react. I tried to hide my discomfort by acting friendly, because I viewed showing discomfort or nervousness as a sign of weakness. I wanted to be intrepid and unshakable, to stay cool under pressure and be in control of the situation.

The tendency among men to hide their unease while they are being sexually harassed was discussed in a 2018 study published in Communication Quarterly. The study says that men who experience sexual harassment may avoid voicing discomfort because doing so sacrifices their sense of control and dominance. They instead try to appear comfortable or use humor to ease the tension.

While I was walking through Kerr Hall, Takeshi approached me and told me he was going to smoke weed in the private all-gender washroom. While we walked past it, he said “Hey, do you mind coming in with me? Just because I really enjoy talking to you.” The hall was empty, and due to construction I was far from the closest usable exit. Escaping the situation would’ve been difficult, so I felt compelled to say yes.

Looking back, I realize he carefully worded his question so I couldn’t say no. How could I refuse without saying I didn’t like talking to him and starting a conflict?

“We have this idea that when people, especially men, experience sexual violence, that they will be able to fight back or exit a situation,” says Prevett.

However, she says when we are in danger the instinctual part of our brain takes over, putting us in “fight, flight or freeze mode” and preventing us from thinking rationally.

“Of all the responses, freezing is actually the most common,” says Prevett.

While we were in the bathroom, Takeshi asked if I wore my pants because they displayed my “bulge.” I said no. He then said he disliked the pants he was wearing and wished to change. He told me to lock the door so no one could enter—so I said I had to leave to go work on something. He said that was fine, and then told me my “bulge” looked “huge.” Not knowing how to respond, I said my penis was just average. He asked to see it. I said no, and left.

Ryerson Security banned Takeshi from campus after I told them what happened. They revealed that Takeshi wasn’t a student. They classified him as an emotionally disturbed person. Returning to campus would get him arrested for trespassing.

Ryerson security, Consent Comes First, and my close friends all supported me, but my other acquaintances were unsympathetic. “Why didn’t you kick his ass?” “Maybe be less good-looking.” “It’s your own fault for leading him on.”

How could I refuse without saying I didn’t like talking to him and starting a conflict?

The police, who I contacted on the advice of Ryerson, only seemed concerned with painting me as complicit.

“Why didn’t you speak up? Were you worried he wasn’t going to be your friend?” one officer asked me.

“Is he gay?” the other officer said.

“Probably,” I said.

“Are you gay?” he asked.

By that point, I felt I lost control of my narrative and felt guilty about reporting Takeshi. Was I overreacting? Had I falsely reported a serious offence?

In spite of being banned, he continued frequenting campus. He confronted me one night, saying, “What I did wasn’t sexual harassment. Sexual harassment would be if I ran up to you and pulled your dick out. Learn the law.”

While I hated those who denied my story, I had spent most of my life being just as aggressive and unempathetic as they were. I was a bully in both middle and high school, and maintained the habit as an adult. I did this partly because I was bullied myself, but also because it felt good. I felt invulnerable. I loved insulting men incapable of out-talking me. I could say anything I wanted and they couldn’t keep up.

I can’t pinpoint when I began to change, but I know I was in the process of doing so last summer as a result of therapy and feedback from my friends and ex-girlfriend. But being harassed by Takeshi convinced me that you could not opt out of toxic masculinity, and that masculinity’s currency was violence. If you weren’t aggressive and dominant, you were a victim.

Prevett calls sexual assault a theft of bodily autonomy and power.

“A way to regain a sense of power and control after assault may come from leveraging privileges we hold, such as masculinity. However, this power…might not be healing and may inadvertantly enforce the rape culture we live in that negatively impacts all of us,” says Prevett.

I often cried myself to sleep, terrified of seeing Takeshi again, angry at the men who made me feel weak. To feel strong again, I relapsed into being a bully. Once again, I targeted any man too meek to fight back. Bullying someone and depriving them of their dignity not only made me feel powerful, it made me feel safe.

“What the fuck is he gonna do?” I’d say after my friends insisted I stop picking on someone. “I’ll flatten him.”

Later, in September, a security guard approached me with good news. Takeshi had been arrested for trespassing and meth possession.

If this story has heroes, it is men like him. Men like the friends who supported me. Men who valued empathy and kindness above all else. Men who actually listened.

Even men like my brother, who I initially avoided telling about Takeshi because of how he responded to me being stalked before. When I told him about how Takeshi asked me to go into the bathroom with him, he took a moment to process it and said, “Yeah, that’s fucked up man. It’s not your fault.”

I wanted to hug him.

*Name has been changed

Leave a Reply