GRADUATING TMU STUDENTS SAY ONLINE LEARNING HAS IMPACTED THEIR FUTURE EMPLOYMENT PROSPECTS

WORDS BY MARIYAH SALHIA

VISUALS BY VANESSA KAUK

After trying to complete a double major in philosophy and music at Carleton University but being unsuccessful, Joseph Gleasure still found himself working at a Real Canadian Superstore in Mississauga, Ont. In his six years at the grocery store, he worked shifts all over the schedule and in more departments than he can remember. One day during a regular shift, he thought to himself, “What the hell am I doing here? I can’t work here forever.”

Three years into his job at the store, Gleasure finally came to the conclusion that he wanted to go back to school, but deciding what he wanted to study was difficult. “Am I gonna pour another $30,000 into a degree that’s going to get me a grocery store job?” He needed a program, unlike the one at Carleton, that would keep him engaged for another four years and get him closer to a career he was truly passionate about—his goal has been to work in fashion purchasing, with the ultimate goal of working in Japan.

Finally, he landed on the fashion program at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) and started in September 2019. He had heard about the program’s reputation for being hands-on and was looking forward to getting the in-person experience he missed out on the last time he was in school in 2014. “[TMU] fashion used to have a really strong reputation for being a technical program,” he says. “People would come under this program and they would be technically competent for the real world.”

But less than a year into the new degree, the pandemic hit and Gleasure says the program’s elements, that he thought previously prepared students well for the industry, were taken away from them when classes pivoted online.

He remembers sitting at his desk with a cup of coffee, paying close attention to his professor who was explaining the details of an assignment integral to the course. His professor explained that each student was to put together a 50-page book of written and photo content they pulled from other sources. The professor stated that in past years, students had to produce a physical 100-page book, with all original written content and two photoshoots that they produced and shot themselves. He sat at his crowded desk, mouth agape at what the assignment had been reduced to because of the pandemic. “I was like, ‘Oh. This is daycare compared to what it was,’” he says.

Now, Gleasure has just seven credits left to complete the program but any job prospects he’s feeling good about after his impending graduation haven’t come as a product of his degree. Instead, they’re a product of the hard work he’s done outside of his schooling.

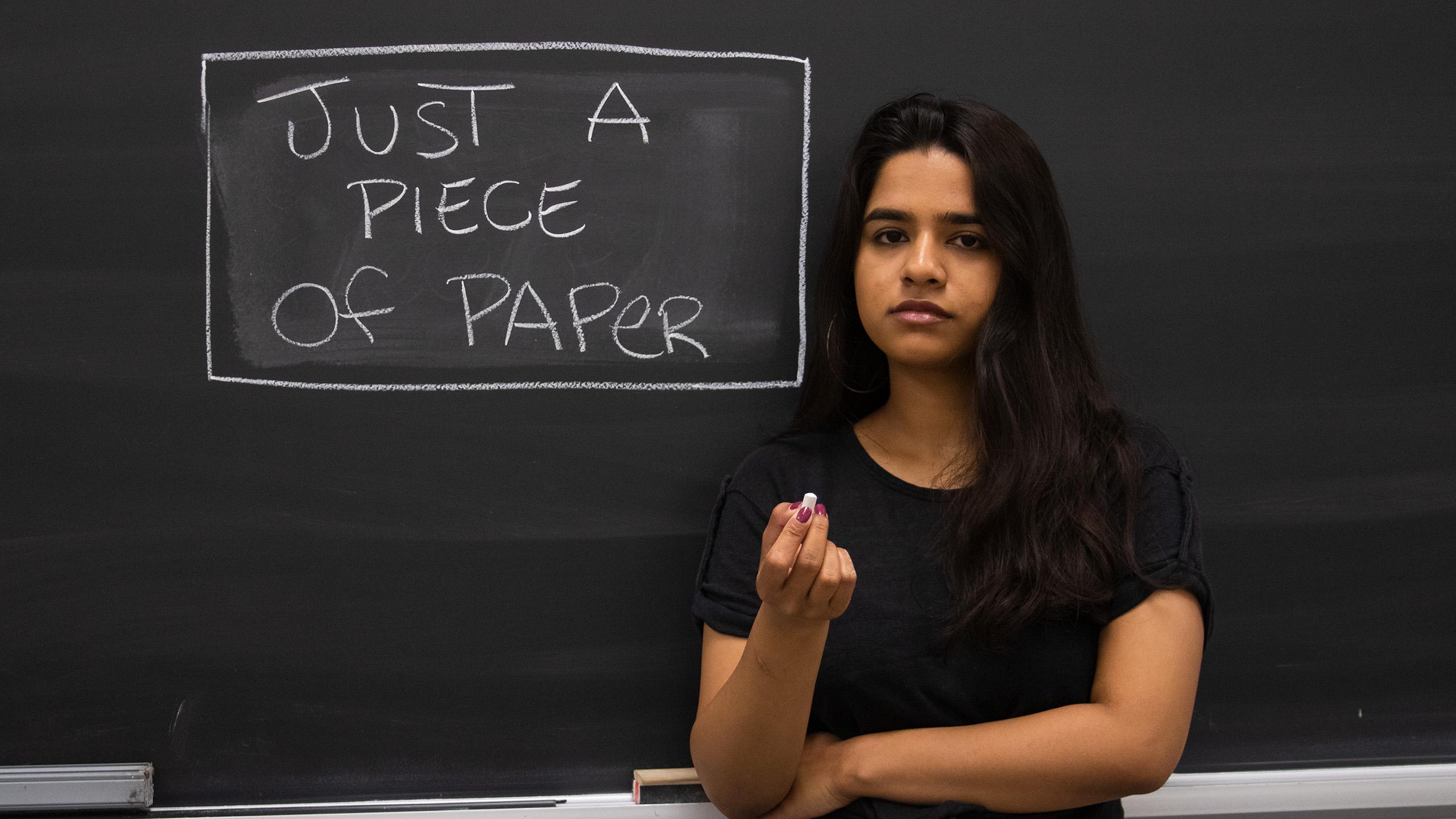

As for his degree, Gleasure says he thinks it’s more of a formality. “Companies need to see that you have this piece of paper on your resume,” he says. Without the degree, Gleasure says people wouldn’t call him back when applying for jobs, so finishing his undergrad was a needed step. Nonetheless, he says he’s still going to make the most of his time left, despite feeling unfulfilled. “I’m just gonna bust my ass and do everything I can to get the most out of this program.”

For TMU students approaching graduation like Gleasure, working towards a bachelor’s degree feels like an expensive step that’s offering less job security than ever. Coupled with two years of watered down learning during online school, the question of how students will be prepared for future employment after graduation looms heavier than ever on their minds. And that’s if they can even find employment.

A Pew Research study found that only 69 per cent of 2020 university graduates were employed by 2021, compared to 78 per cent of 2019 graduates, who were employed by 2020. According to Statistics Canada, 10.3 per cent of university graduates were unemployed in 2021, a considerable jump from 7.6 per cent in 2019. Last month the unemployment rate in Canada rose by 0.5 per cent to 5.4 per cent. While this rate is still low in comparison to the record-high nationwide unemployment rates in previous years, in August, employment dropped amongst Canadians between the ages of 15 and 24.

“Everybody got hit [by unemployment rates], but certainly students are among the worst. Students at all levels,” says Anil Verma, a professor emeritus of industrial relations and human resources management at the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto. He says for older students, especially those in university, it was tough for them to enter university, graduate, do lab work, get a job and be integrated into a new organization.

Still, Verma says getting a university or college degree is like a stamp on your forehead. Then, students have to go to employers with their degrees and say, “‘Look, I did my four-year course.’”

Verma says in the past, bachelor’s degrees were enough for employers to hire a candidate. Now however, employers are also looking for strong skill sets. “Whether you’ll be hired depends on your ability to demonstrate that you can use your knowledge to solve problems,” he says. “And this trend is increasing.”

He says getting a university degree is like getting a hunting license—having one doesn’t automatically mean you will get a deer. Similarly, a degree is just one step toward the greater goal of finding stable employment, not the key. As a result, Verma says students will have to work harder to make themselves more competitive candidates, like seeking out additional professional courses, connecting with employers before reaching out about jobs and in some cases, skill tests administered by potential employers.

Gleasure, now in the final year of his degree, says there is a noticeable gap in the quality of work students produced during the pandemic, compared to before. He attributes this to a lack of engagement when classes were online, reminiscing about the number of his classmates who’d attend class in their pajamas.

“There is a noticeable difference in skill set,” he says.

rista Shoebridge still remembers her first day of university, on a Tuesday in September of 2019. Relieved that it started at 10 a.m. and not at 8 a.m. like some of her other classes were scheduled to begin, she went to her lecture and made conversation with some classmates she recognized from orientation.

Since 2017, TMU’s nursing program has consistently made the Maclean’s top 20 list of best nursing university programs in Canada, so the choice of school for Shoebridge was easy. With the program boasting a hands-on approach, she was excited to get into practical classes. Then, the pandemic happened. At the time, the now-fourth-year nursing student was eager to start saving time and money on her commute from Mississauga, Ont., since classes were shifted online. “I didn’t have to worry about loading up my Presto card,” she says, “I knew that I just needed my computer to work.”

But when her practical training began in the midst of lockdown in her second year, Shoebridge says she missed out on opportunities for hands-on learning that she’ll now never be able to experience. Instead of using labs and getting in-person instruction, she and her classmates were given a kit to do skills labs at home. “I had to put my fan next to me at my desk here, run an IV and count the drips,” she says. She had to insert a needle into an orange for her skills video assessment, conduct wound care on the back of her binder and practice doing sterile dressings all from home.

For Shoebridge, missing out on these labs in person feels like a loss that’s particular to her graduating class; after that lab, the program didn’t offer the same practical experience again.

In the winter semester last year, Shoebridge and her classmates came back to campus for one day of in-person labs. She says students were rushed through what felt like 10 weeks worth of content in a mere eight hours. She remembers her instructor saying, “‘OK, we’re gonna do injections, we’re going to do catheters, we’re going to do this, we’re going to do that and then we are out of here by 4 o’clock.’”

“I’m gonna test you and then goodbye. We’ll see you next week online,” she recalls being told.

For Shoebridge, this was frustrating. “We’re supposed to have so many other hours and days and knowledge and we have none of that.” These are some of the hands-on skills that many TMU students like Shoebridge and Gleasure did not get a chance to learn, especially when everyone was at home during online school.

“It’s always really important to make the distinction between knowledge and skills,” says Steve Joordens, a professor of psychology at the University of Toronto Scarborough. He says even before the pandemic, universities weren’t doing a good job of preparing students for life after graduation.

By having little opportunities for students to have face-to-face interactions with professors, they aren’t learning how to deal with uncomfortable social interactions, which Joordens says is imperative to being able to get a job.

Now, Shoebridge says the only reason she feels confident about her job prospects is because of a shortage of nurses in Ontario. Earlier this year, emergency rooms across the province were closed because of depleted nursing staff.

She used to think she wouldn’t get hired out of school, because like her fellow peers in the program, she had less experience. Now however she says “I will for sure get hired, no matter where. Because it’s a crisis.”

oday, Gleasure has an end goal of a career in fashion at the front of his mind. With only a year left of his degree to complete, he feels confident about his employment prospects, but he doesn’t think his degree is what’s preparing him for the workforce. Instead, it’s because of his job in marketing for a high-end furniture dealer in Toronto.

“I got that job because of work I had done in social media on my own time, completely unrelated to school,” he says. Earlier this year, he was awarded the Helen and Sulo Hutko Award by the TMU School of Fashion, for his work contributing to fashion magazines like _AD magazine, SHELLzine, Terminal 27 and for co-founding My Clothing Archive, an archival fashion page, which grew to 25,000 followers on Instagram and 13,000 on TikTok.

“If I was relying purely on my education, credentials, I don’t think I would have gotten that position,” says Gleasure. “I feel like there’s a lot of people in that exact same position in my program right now.”

With files from Fatima Raza

Leave a Reply