By Donald Higney

One of the greatest concerns following the announcement of Ryerson’s smart campus is the potential of hacking through smart buildings, but according to the university, none of the data collected could personally identify students and faculty members.

Ryerson has been working with Vancouver-based system integration company FuseForward since 2016, who is assisting the university with smart building optimization and infrastructure. The partnership is now turning to the optimization of Ryerson’s downtown campus through streaming data between smart devices and sensors.

In the Dec. 10 presentation “Building Smart Infrastructure: An Inside Look at the Ryerson Smart Campus,” assistant architecture professor and smart systems expert Jenn McArthur said that one of the biggest fears of smart buildings is the possibility of hacking specific features of the building to get through to Ryerson’s broader security system.

The Daphne Cockwell Health Sciences Complex (DCC) is currently one of the buildings being used for smart campus testing. According to Ryerson experts, there are a lot of barriers to entry that make it difficult for someone outside of the network to try and access it. So how do these networks function?

The devices and sensors that control heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) in the DCC communicate through wires that are hidden to the public, according to Karim El Mokhtari, a senior researcher in Ryerson’s smart building analytics research group.

HVAC sensors are also connected to their own private network that isn’t accessible globally, otherwise known as network segmentation, according to Brian Lesser, chief information officer for Ryerson Computing and Communications Services (CCS), in an email to The Eye.

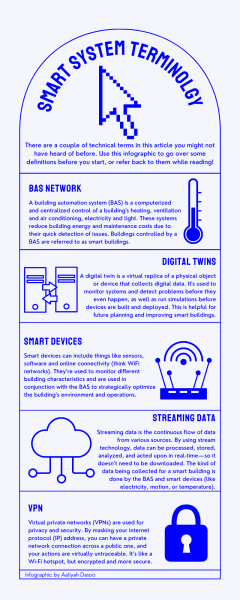

HVAC sensors are part of the building automation system (BAS) network, which is also responsible for lighting and electricity. Information from administrative computers or academic labs stays on their own separate networks.

Network segmentation is the first step to protect the information in Ryerson’s buildings, according to Lesser. “We don’t want a remote attacker to gain a foothold somewhere else on Ryerson’s network and then be able to get to these systems.”

CCS is responsible for granting access to the BAS network to those at Ryerson who request it, but only to read information, like for El Mokhtari’s digital twin system.

“There are many ways to leverage compromised systems and user accounts”

To transfer information from the BAS system, a one-way connection is established to another system on a remote network. A virtual private network (VPN) connection is set up to secure the transfer of information from that network to an off-campus system for security information and event management.

“The goal is to avoid attackers being able to connect to [networks] remotely or for any system on campus to connect to them that doesn’t need to,” he said.

According to Lesser, the most common motive to hack Ryerson’s information systems is financial gain. “There are many ways to leverage compromised systems and user accounts. Business email compromises, identity theft, ransomware, banking trojans.”

Other potential reasons could be to access confidential research publications that are not available in other countries and hacktivism, meaning people who obtain access to computer files or networks without permission to advance social or political goals.

Lesser said although attackers may not know what is on the BAS network, it’s still a potential target. Reasons for a potential hack include installing ransomware and holding data for monetary gain or just to shut down systems to cause problems.

According to Lesser, Ryerson students and community members’ personal information have little risk to hackers in terms of the smart campus project since the information that would be targeted has to do with the building’s operations, but without doing a complete audit of the systems the true risk is unknown.

Although not connected to the security features of the project, El Mokhtari has been working on machine learning algorithms for the fault detection aspect of the smart campus. Machine learning is the development of computer systems that can learn and adapt without following explicit instructions to analyze patterns in data.

He is also creating a digital twin for the DCC, which will allow him to see the current state of different sensors.

“The digital twin allows you to ask questions without going to the real object,” said El Mokhtari.

Although the smart campus poses no threat to unlawful use of their personal information, some students have other concerns with the project.

Ryan Lukic spent three years in Ryerson’s business technology management program before transferring to Centennial College’s computer technician program. He said he thinks the university needs to refocus its efforts on trying to centralize the operation of information systems on campus.

“There are numerous bureaucratic issues that the university itself has that I think needs to be addressed before you can integrate a brand new system into Ryerson for the management of the campus,” said Lukic.

Some of these bureaucratic issues include travelling between different buildings to deal with long wait times with Ryerson faculty and administration.

Even with the student critiques, the project’s main goal is to make the campus infrastructure more comfortable for those who study and work at Ryerson.

“We’re trying to work [towards completion of the project] to increase the comfort of people and we are also measuring the number of complaints,” said El Mokhtari. “So if the number goes down, it means that our algorithms are working as expected.”

Leave a Reply