By Jonathan Spicer

At six a.m. every morning, truck horns went off. And at six a.m. every morning, Julie Nadeau opened her eyes to the damp tent walls around her.

“One night, I dreamed of planting all night and when I woke up in the morning I was so tired. I just planted 2,000 trees [in the dream] and didn’t get paid for it,” Nadeau, 22, said of a summer morning in 2001.

She was one of some 60 people who planted trees in the rolling boreal forests north of Manitouwadge, Ont., during May and June.

“It was one of the hardest things that I did in my life; now I appreciate life a lot more,” Nadeau said from her home in Montreal where she studies biology and environmental sciences at McGill University. Like the majority of planters at the camp, it was her first time tree planting.

“At first, you’re just dead … and just want to go to sleep. But after a while, you don’t feel it as much.”

Nadeau thought back to her nightmare as other planters unzipped their heat-locked sleeping bags to freezing temperatures, or struggled to pull on frost-covered, steel-toe boots.

The challenge was there, in that waking moment, when planters either cursed the booming truck horns or embraced them for the rest of the day. That day — and the entire summer — was won or lost with that mental decision.

Only then do you worry about duct taping your planting fingers to protect them from scraping rocks and cracking from the cold.

“The mornings were always the worst,” said Adina Israel, 21, another first-time planter. “It was so cold and this was just the beginning; there were 10 hours ahead of you.”

Israel decided to tree plant because she wanted a change from her windowless university residence.

“I needed some fresh air; that was a big part of it. I wanted to live outside for two months and have some time to think — but if you think, you plant too slowly,” she said.

There’s pressure to persevere when doing piecework, where every extra tree in the ground means extra money in a planter’s pocket.

For 26-year-old Juan Davila, an environmental studies and international development student at the University of Toronto, the morning was more of a quiet time to prepare for the day.

“It could be sunny or rainy, but there’s fresh air, and when I got in the van [to head out to the planting block], my mind just focused on planting trees,” he said. He added that it was important to visualize his plot of land before slashing into it with 30 pounds of seedlings hanging from his hips.

On the blocks of land, which were usually clear-cut a few years prior and only accessible by crumbling logging roads, individual planters put flags around a section for themselves. They fill it with either jack pine or black spruce seedlings — the type of tree depends on the terrain, and are spaces about six feet apart. Work days vary from eight to 12 hours, time enough for planters to walk, crouch, crawl and run approximately six kilometres.

A common planting technique is to use one hand to grab the seedling and the other to shovel. After a hearty breakfast, and with packed lunches on hand, planters arrived at their block (same as the day before or a new block of land) around 7:30 a.m. They planted for about two hours before filling up with seedlings from bins at the side of the road.

Rain or shine, snow or hail, there are trees to be planted. The only day that the Manitouwadge Camp was pulled out early was when a windstorm toppled trees on the clear-cuts. One planter was even hit by a falling tree and driven to the nearest hospital for spinal X-rays.

“I hate the job,” Davila concedes, his native Colombian accent radiating out from under thick black dreadlocks. “I think everyone hates the job and everyone hates to be out there,” he said. “But when you have such a beautiful landscape to be in for two months without being able to see a building … it’s incredible. And secondly, being able to create such a nice relationship with people. I would do it again for sure.”

Mike Bays, a 21-year-old from Winnipeg has no doubt that he’ll plant again next summer. “The money is there, not so much in the first season, but it usually takes coming back a second time,” he said.

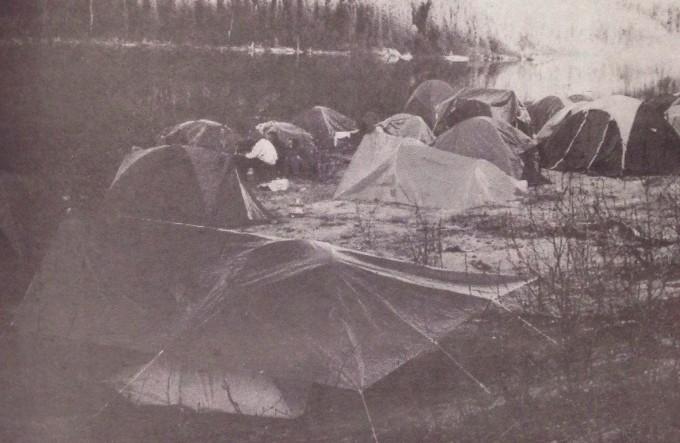

In fact, he wished he lived at the bush camp, even though it consisted of little more than a cook’s trailer, two dining mess tents, four portable outhouses, and planters’ individual tents.

The crew mainly planted for six days. They had a routine for their day off. The day before would end around six p.m. And planters would drive into town, check into a motel, shower, go to a bar and spend the next day relaxing.

“It’s not like the real world,” Bays said. “You don’t have to worry about things because it’s all planned for, like a mini vacation in a way.”

For some, it was not a vacation where planters picked up a paycheque on the way home.

Planters were paid between seven to nine cents per tree, depending on the land and degree of scarification (broken up surface of topsoil). The planting company, Outland Reforestation Inc., charged a daily camp cost of $25 for food, gasoline and staff salaries (like supervisors and cooks), which was deducted from each worker’s earnings. Depending on personal capabilities, planters could plant 300 to 5,000 trees per day. A two month contract could earn a planter as much as $10,000 or nothing but a body ridden with mosquito bites.

The mental challenge of pushing yourself farther than the day before is the most difficult, Nadeau said. “I’m glad I [tree planted] no matter how it was, but at the same time, I was disappointed that I wasn’t better.”

But what planters lack in economic gains, they make up for in personal gains.

“Tree planting made me learn a lot about myself,” Nadeau admitted. “I realized that even if I’m not happy, I can tough it out and be strong.”

Living minimally — basically off what you can carry on your back — makes you realize how little you actually need to live, Nadeau said.

Bays said that tree planting changed his life. “Other work that you do afterward will seem so much simpler compared to the work out there.”

“One day, I was with two other guys on a large piece. We were soaked and the grass was up to our hips so you had to plant when you couldn’t see where you were planting,” Bays said.

“I hate the rain, and it rains a hell of a lot when you hate it,” he said.

Israel’s horrible moments had more to do with the bugs than the rain. Afternoons of replanting — walking over an old piece of land where trees weren’t planted properly, and not getting paid for it — when swarms of mosquitoes, deer flies, black flies and sand flies drove her to the edge of sanity.

“It made me stronger, mentally. I never really had to do physical work before tree planting, but if you think positive, it makes the job easy,” she said.

For Davila, too, the experience was about the challenge.

“It’s not about quitting or not quitting. If you go tree planting and you are able to survive one full day, that’s it, you did it. Many people in the world haven’t experienced putting their body and their mind in that situation.”

Davila’s last planting day was especially brutal. It was raining and bitterly cold while he was coughing and spitting up blood. After visiting the Manitouwadge Hospital for two days, with pneumonia, he headed home to Toronto where he stayed the night in a city hospital.

“I thought I was invincible and didn’t take care of myself. Now I’ve learned to put limits on myself,” he said.

But it’s the good memories that planter take away with them. Like the time Nadeau planted 1,000 trees in a day. Or after a day’s work when the setting sun is beaming through the van window, and the whole crew is dirty, sweaty and exhausted.

“At the end of the day, you can reflect on some really tough work,” Nadeau said. “You think, ‘that’s the reason I did this.’”

Leave a Reply