By Skyler Ash

Nika Zolfaghari grew up in a family of engineers—male engineers. Her dad worked as an industrial engineer, and her uncles electrical and civil. She grew up not quite knowing what she wanted to be, but she knew that she liked math and science. Still, she thought, “engineering is for boys,” and because she’s a girl, she didn’t see it as an option.

In her senior year of high school, Zolfaghari walked through the campus at Ryerson and made her way to the lower floor of the George Vari Engineering and Computing Centre. She sat down in a classroom with about 15 other students from Grades 11 and 12, mostly girls. As she unpacked her things, she looked around to see that everyone was just as nervous as she was. She plucked up some courage and began talking to a few of the kids around her. The tension eased.

This was Zolfaghari’s first day of Ryerson’s Research Opportunity Program in Engineering (ROPE), a month-long summer program that gives kids the chance to work with engineering graduate students and professors at Ryerson.

Nine years later, Zolfaghari has her undergradaute degree in biomedical engineering and her master’s in electrical and computer engineering, both completed at Ryerson. She works at the university as the engineering enrichment and outreach coordinator.

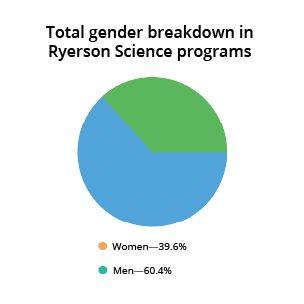

Graphic: Skyler Ash

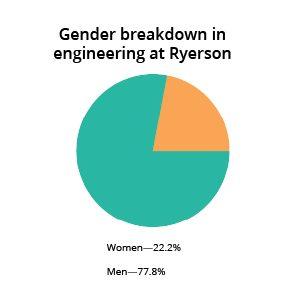

At Ryerson, women made up 22.2 per cent of the Faculty of Engineering and Architectural Science in 2015. In the Faculty of Science, the number is slightly higher, at 39.6 per cent. Gender imbalance in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) programs has always been an issue, but despite a growing emphasis on promoting these programs to women, little progress has been made. Post-secondary institutions boast inclusion, but many have overlooked the root of the problem. It comes down to the way girls are culturally conditioned from a young age, long before they fill out their university applications.

In a male-centric profession, different perspectives are essential in changing what we research, and how. But low female enrolment numbers in STEM programs are the norm at universities across Canada. At the University of Toronto, January 2015 saw a “record” number of women enter their first-year engineering program, at 30.6 per cent. Similarly, at Memorial University of Newfoundland, women make up 26.5 per cent of engineering and applied science and 52.7 per cent of the science program, while at the University of British Columbia, women make up 23.3 per cent of the faculty of engineering. There are few official statistics on the number of trans or non-binary people enrolled in these programs.

“Record” numbers may seem optimistic, but outside the post-secondary scope the realities are even worse. In 2015, according to a poll from polling company Ipsos, only 22 per cent of people working STEM jobs in Canada were women.

The concept of the “glass ceiling”—a figurative invisible barrier preventing women and minorities from climbing the corporate ladder—is often described as a barrier for women. Imogen Coe, dean of the faculty of science at Ryerson, says that for women in STEM, it’s a glass obstacle course. As you navigate your career path, she says, you’re left to maneuver around unexpected “walls”—you either break through them, or get knocked off the path altogether.

From a young age, girls are often taught to be overly feminine, while boys are given “practical” toys: from construction sets to electronics. Coe notes, however, that kids are “born curious,” and that they’re all natural scientists. They just need to be given the chance to explore.

In the same Ipsos poll, 28 per cent of women in university and 38 per cent of graduates said they would have gone into STEM programs if they had proper support in school. “If you talk to young women, sometimes they’re tired of feeling like they don’t fit in, and they want to fit in,’” says Coe. “It’s important to promote diversity in pretty much any human endeavour.”

Graphic: Skyler Ash

When Lexi Benson was seven years old, she remembers watching her father work on the circuit breaker while he was refinishing the basement.

She looked around the room, wondering how it was made and why the lights turned on. As her father trifled with the wires, she started to see how everything came together.

Her parents put her into math tutoring to help compensate with the difficulty of learning a new language in French immersion school, and she never lost her curiosity for tinkering. Before long, Benson was taking things apart and putting them back together to understand how they worked. Her parents began to notice her interest in math and science and suggested she consider engineering.

Now, Benson is in her fourth year of aerospace engineering at Ryerson specializing in the avionics stream, which is a mixture of electrical and aerospace.The first in her family to go to university, she is working alongside Zolfaghari as an engineering outreach ambassador this year. As of 2015, the aerospace program at Ryerson was 13.7 per cent women. “I’m about one of 10 girls in my year,” says Benson. In some of her labs, she is the only female.

“When I tell people I’m in engineering, most of them say, ‘Oh, really? You?’ and I respond with, ‘What’s that supposed to mean?’” She says that people are often surprised by how competent she is when it comes to math.

Coe refers to these misconceptions as the unicorn concept. Women in STEM are viewed as “rare, special, amazing, almost imaginary beasts.” But many women in the program do go on to become successful engineers—something Coe says is “not something to feel special about.” Instead, women’s presence in these fields needs to be normalized. “If you love physics, go do physics. If you love math, go do math,” says Coe.

High school test scores show that women often outscore men in both science and math, but a 2014 study revealed that women with degrees in STEM tend to underestimate their abilities. Their male counterparts, in contrast, overestimate themselves. The same study showed employers were two times more likely to hire male candidates, because they seemed more qualified and confident.

During her first year at Ryerson, Madeleine Catz was studying for her calculus final with a few other people in her program. She completed the answer to a practice question and waited for the others to finish up. When she gave her male peer the answer, he told her she was wrong and proceeded to check with a TA and in the back of the textbook. Turns out she was right all along. “I guess we’ll give you that,” he said.

“You know, one third of engineers end up dropping out?” a different male told her.

After a while, the jokes stopped being funny. Men in her program repeatedly told her that she was going to fail. Catz told them to stop, and when they didn’t, she started ignoring them. Ironically, of the guys who taunted her one fell behind in school and the other dropped out because the program was too difficult.

Catz is in her fourth year of civil engineering in the transportation stream. Although she’s almost done her program, she still deals with male classmates who doubt her abilities.

Some programs are worse than others. In mechanical engineering and computer science, there are approximately 8 per cent women. Before the ‘80s, more than a third of the people pursuing computer science degrees were women. This number dropped 10 per cent when home computers were first made available and marketed as gaming devices for men.

“I used to think, ‘Programming is for boys’,” says Catz. “A lot of girls have that stereotype.”

“What we should be doing is identifying the barriers and getting them out of the way so that everybody has a fair chance”

Both Catz and Benson say popular culture plays a role. “Movies just always show guys,” says Catz. Take Bill Nye, Neil deGrasse Tyson and the guys from Mythbusters, who dominated the stereotypical image of a scientist.

Zolfaghari says that Ryerson has made it a priority to have more women in their programs. Working as an outreach coordinator, she organizes events in order to get girls thinking about science and math. These programs include events such as Go ENG Girl and Go CODE Girl, which invites young girls to come to Ryerson to participate in engineering and coding activities. Alongside other Canadian universities, Ryerson has been hosting these events for 12 years.

Zolfaghari also organizes Pitch Black, where Ryerson engineering students go to Grade 9 science classes to help the kids build circuits. The goal is to get students, girls especially, interested in taking Grade 11 or 12 physics, which is a requirement for engineering students at Ryerson.

Zolfaghari says it’s about trying to rebrand engineering so women know it’s a viable option for them.

“Google the word ‘engineer’ and you’ll see guys in construction hats,” she says. “We’re always coming up with new programs and new ways to engage girls.”

Ryerson also has groups that support women in STEM programs, such as Women in Science at Ryerson. The group was created to help mainly graduate women to network and fine tune their professional development skills. The Undergraduate Women in Science at Ryerson group, and Women in Engineering have similar goals.

“What we should be doing is identifying the barriers and getting them out of the way so that everybody has a fair chance to get where they want to go,” says Coe. “If we want a good standard of living, if we want economic development, if we want the best science we can, if we want everybody’s voice to be heard, we need diversity. It’s not just a good idea, it’s essential.”

It was a crisp Saturday in September in a big lecture theatre at Ryerson’s George Vari Engineering and Computing Centre. About 60 girls, grades 7 to 10, sat with their parents as Zolfaghari welcomed them to the Go ENG Girl event. Excited whispers went back and forth from daughter to parent.

Zolfaghari went through a few explanatory slides, and then stopped. “We’re going to do a little quiz,” she said. Some girls looked excited, others looked apprehensive.

The screen said, ‘car battery’, ‘sewing machine’, ‘circular saw’, ‘dishwasher’ and ‘modern eyeglasses’. “Now,” said Zolfaghari, “Which of these were invented by a woman?” Girls and parents drew close together and discussed it for a minute. Zolfaghari went through the list, as various people raised their hands to vote on which creation was a woman’s invention. Pausing to let people quiet down, Zolfaghari said, “Trick question: they all were.”

Girls looked at their parents, eyes wide with excited smiles spread across their faces. “Today, we all get to be engineers,” said Zolfaghari. As the girls split into groups to complete activities to teach and test them on their engineering skills, one girl turns back to her mother to yell goodbye, waving frantically. Skipping down the steps, she joins her group to get to work, because today, she is a girl, and she is an engineer.

Leave a Reply