By Devin Jones

It had been a year since Jeff Chiu’s grandfather, Ruo Yu Gao, passed away. As he helped his mother sift through a pile of his old belongings, he came across a large stack of loose of pages held together with simple twine. They contained handwritten Cantonese notes about policy for the Chinese government and documented his grandfather’s time as a lawyer, and his life after immigrating to North America.

Chiu’s grandmother wanted to get rid of the papers for reasons he never really knew. But for him, the memoir represented a complex relationship that warranted further exploration. He yearned to understand and access the words his grandfather scratched into the page, but he was unable to do so—despite holding it all in his hands.

In death, we’re forced to reflect on the complexities of a full life, but at the expense of never understanding the entire picture. There are the rare occasions when the things left behind by the dead represent their personal thoughts and philosophies. Journals, especially—a personal and private vessel of memories in someone’s life—provide a catalyst for celebration, joy and reflection.

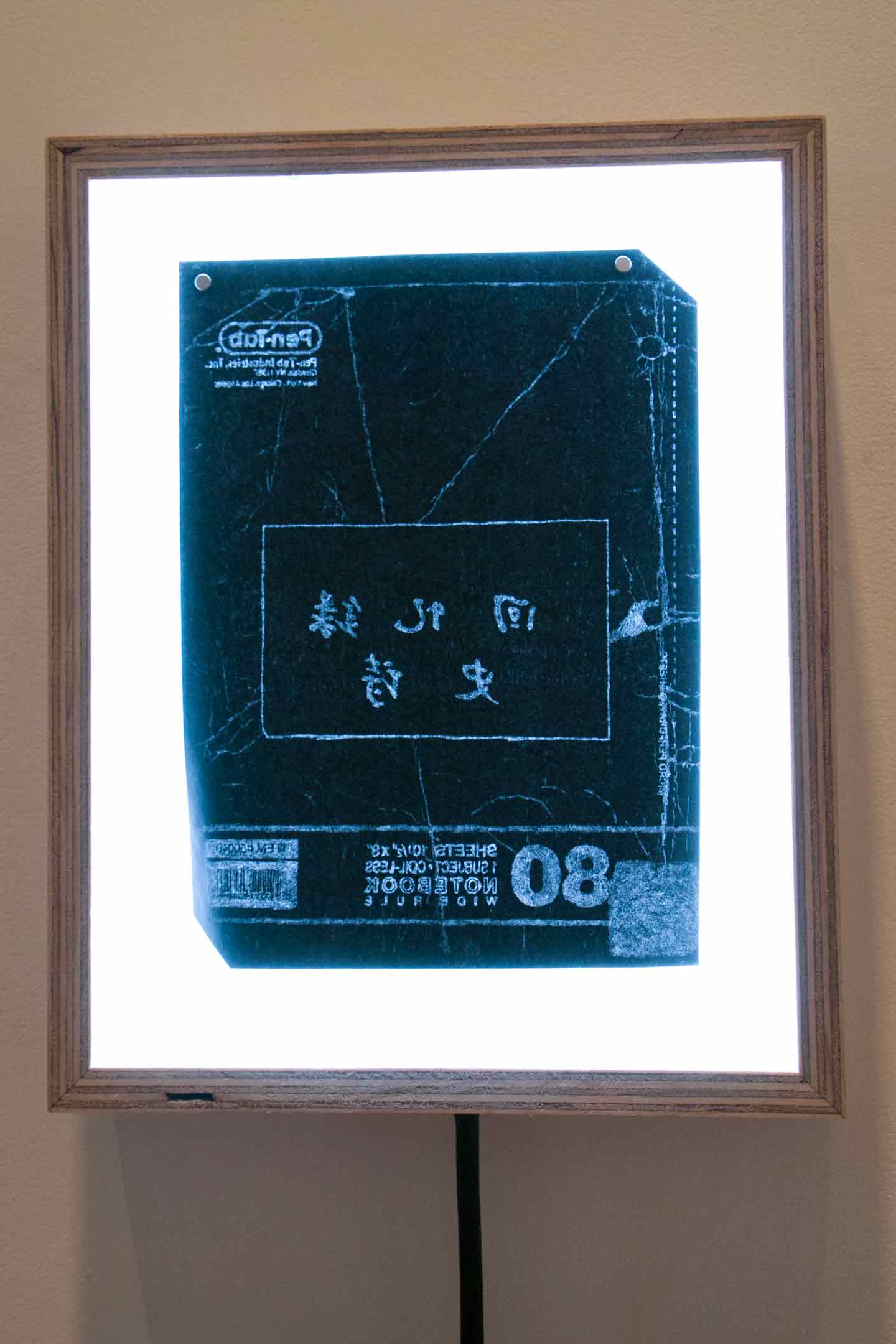

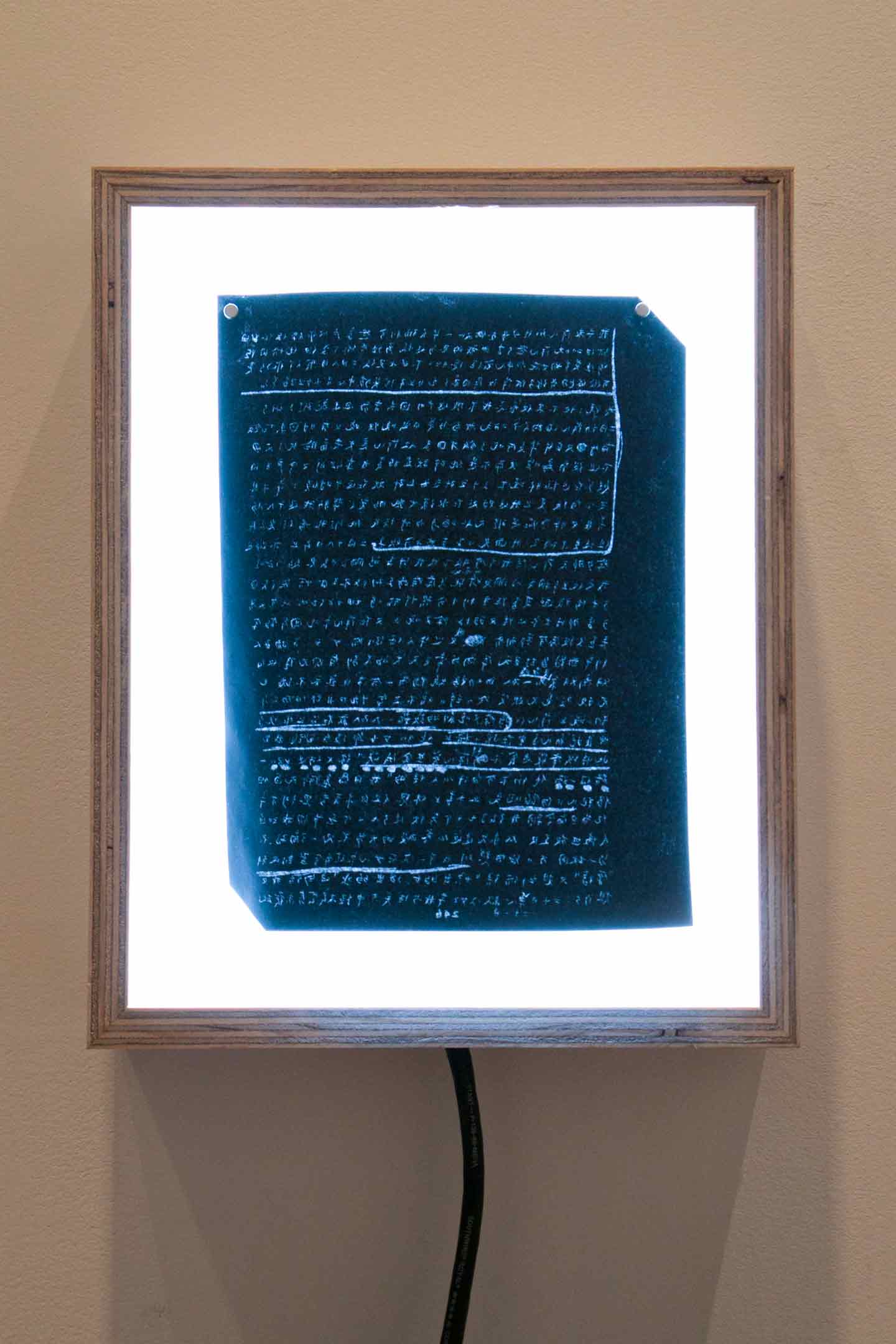

In an attempt to further explore the meaning behind the journal he found, the fourth-year photography student culminated the bound pages into an art exhibition within the Ryerson Artspace at the Gladstone Hotel. Titled “Ancestral Home,” it featured the pages of his grandfather’s memoir on display behind acrylic casing. Chiu was present to answer questions and provide extra details about his grandfather’s long immigration from China.

“If it didn’t change the literal understanding of him, it definitely changed my emotional and symbolic understanding of who he was,” he said. “I did the tracing of the book, and it was very cathartic and I felt like I was drawing the lines he drew, writing the words he wrote.”

Photo: Camila Kukulski

Chiu would visit his grandfather maybe once a year. A very calm and poised man, he was always encouraging of the projects Chiu took on. Chiu says he was one of the only grandparents who didn’t find it strange when he decided to attend Ryerson for photography. Despite the generation and language barrier that existed, he says the lack of literal understanding produced “something human.”

“You’d always get these surface questions and basic conversation that sometimes would break the barrier and get into something human about each other,” Chiu said. “Constraints of time and generation, I think, really buffered our relationship.”

Initially, translating the handwriting was what Chiu wanted to do. But it proved to be more difficult than he expected. There’s a certain “woven” nature to the relationship between the words in his grandfather’s language that adds an extra layer of texture not found in the Western world, he said.Over coffee, he tried to explain it to me the best he could: In the English language, nouns and objects are prefaced by “the or a.” But in Cantonese and Mandarin, the noun or object is introduced with a type of adjective that cements its size, shape, position in the world or even its movement. These types of introductory words give sentences colour, but they don’t exist in English writing. Had the words been translated, he said his grandfather’s experience would become flat, and the magic of his life and experience would be lost and lacking context.

“I initially wanted to translate it all and to understand everything,” he said. “But as I got closer and closer to translating it, I realized the difficulties and the ethics of translation, and betraying the original in a sense. I didn’t want to obscure his voice. But that’s just one perspective.”

Photo: Camila Kukulski

Photo: Camila Kukulski

A few of the pages at the Gladstone exhibition look like X-rays. Chiu began copying out his grandfather’s pages and using carbon paper as a transfer medium. When he placed them on top of a box light, it gave off the grey-blue hue of a hospital X-ray. These box lights and carbon copies lined the faux wood walls of the Gladstone art space, with acrylic stands supporting the physical pages placed in the middle of the room.

In the description for the event, a question is posed: Maybe every life is a secret, and through the replication of an original object different nuances and subtleties can appear.

It’s a seldom expressed paradox, learning more in death than we do in life. The small recesses of the recently departed, infused with details and morsels of information that come to us only when they’re no longer here to provide context. But as Chiu did with his grandfather, we can come to understand part of their lives. And if we take our time, we might just be able to assimilate pieces of them into our own existence, scratching our own ink into their pages.

Leave a Reply