By Emma Buchanan

During her second year in Ryerson’s film program, third-year student Robyn Matuto had written a script about Filipino culture, a story that was based on her relationship with her mother.

As part of a second-year screenwriting course in Ryerson’s film curriculum, students are asked to submit scripts, some of which are selected for students in lower years to direct and produce. The course outline states scripts in the course are “designed to serve as the student’s scripts for subsequent production courses” and “all scripts will be forwarded to the second-year production instructor.”

“I had always intended for that script to have a Filipina actress in it, be directed by a Filipina, hopefully me,” said Matuto.

But that’s not what happened. Matuto found out from a “friend of a friend” that her script had ended up as material for students in a lower year production class to produce. She followed up with the lower year students and found out that the ethnicities of the characters in her script were changed to Spanish, which she felt had negative implications because of the historical relationship between Spain and the Philippines. She said it also ignored the Tagalog language in her script.

“[Image Arts] doesn’t email you, the professors don’t touch base with you whether or not it’s okay to use your script,” Matuto said.

The changes were especially troubling for Matuto, who had followed up with her professors after submitting her script. She expressed that she didn’t want her story to be given to “someone who might not understand the cultural nuances.”

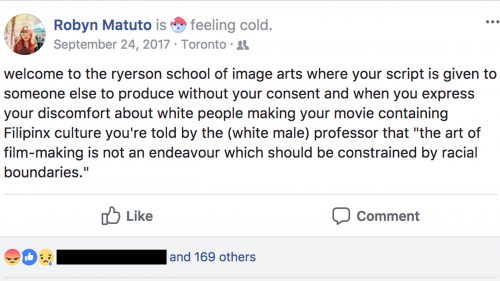

Matuto voiced her complaints on Facebook in September. The post was on her account, but ended up being spread to a wider audience. After sharing the post, other students approached her with similar stories about usage of scripts.

“Other people are coming up to me saying…it’s happening to them too. And, at the end of the day, it’s trying to make that learning environment a little bit more inclusive and like without having to poach from someone else’s experience,” she said.

Robyn Matuto’s original post about the issue on Facebook.

Film Program Director Gerda Cammaer said Matuto’s case was brought to her attention.

“I think that there is a lot of misunderstanding, and I regret what happened. But you know, the reasons why she was pulling her script were not entirely founded because there was nothing in the script particularly that the students could recognize that it had to be a Filipino story,” Cammaer said. “If those things are so essential to a script, they should be in the script and they weren’t.”

Scripts submitted to Ryerson are used for learning purposes within the school, but students retain intellectual rights, said Cammaer.

Cammaer says, from her understanding, students are usually “happy” when their scripts are chosen to be given to lower-years.

Andres Herrera, a third-year film student says the program has poorly handled his films featuring POC and LGTBQ+ narratives. In several instances, Herrera said he has felt he’s had to explain the “very nuances of what queer experiences can be like.”

When Herrera wrote a script about a toxic relationship between two men he had to constantly explains aspects of the project. His professor did not understand Grindr and Tinder or the implicit communication of his characters: the idea that his characters couldn’t call themselves by “certain labels.”

“It was trying to rewire people’s head around that and trying to connect the dots,” said Herrera. “Which is not the worst thing, but it’s something that is systemic in our program because it’s very saturated in white, hetero, cisgender people.”

“We’re not taken seriously in our program. It’s even harder if you’re a woman, and you’re a woman of colour that is a much harder thing to get into because that’s just how the industry works”

Neave Wright, a second-year film student, has been on the other side of the script dilemma.

Wright received two scripts last semester in a second-year production course, both dealing with racialized narratives. She said she was unclear on whether the scripts were willingly given.

“I would say both the scripts I received last semester were kind of problematic in the sense that I am a white female, so getting a script about a Vietnamese family, which does reference Vietnamese culture significantly throughout, is not something I felt that I could speak to without getting in contact with a cultural advisor,” she said.

Wright said that following Matuto’s Facebook post, many second-years did their own research after receiving scripts.

“That incident incited other people searching for cultural reference points so they could actually properly represent the material in their stories,” she said.

Wright and her production team were able to contact the original writers because their names were on the script.

She said they met with the screenwriters to discuss the script, and stayed in contact with them throughout the production of the film.

Chair of Image Arts, Blake Fitzpatrick, said the faculty recognizes the authorship script issue and that the faculty has been discussing resolutions.

“What we’re going to do is put in place something where students will have to sign a form that says they’re in agreement with their scripts being used and if they don’t want to, there’s no pressure, they don’t have to.” Cammaer said after Matuto’s case, the Images Arts faculty are drafting a new kind of author declaration to be signed by students at the beginning of second-year courses.

“It’s been implicit in practice, now it’s going to be explicit,” Cammaer said. But Wright says that after Matuto’s situation went public at the beginning of last semester, the new authorship declaration was mentioned briefly in her second-year writing class. She hasn’t heard anything about a new authorship since.

“That’s kind of troubling because we have submitted a handful of scripts. Everyone has written a script and that’s about 90 of us, so that’s a bunch of scripts that have been given over and I know that not everyone is keen on handing the rights to their script over.”

Naiyelli Romero Agüero, a fourth-year film student, says she felt the experience of script sharing was different for her peers.

“People felt insulted and just kind of violated, if I can use that word, just because it wasn’t made clear to students that that’s what was happening.

“It’s something that is systemic in our program because it’s very saturated in white, hetero, cisgender people”

However, Romero said that because the process was different in her year, there seemed to be fewer issues.

“We were a little more lucky because we did get to use the scripts from our own year… so people got to work with the writers and everything because we all knew each other so we were okay with it,” she said.

Matuto says she was not contacted by faculty with any information following the incident about the new authorship declaration.

“I found out through friends again, even though I was really keen on helping them. And I wasn’t trying to be antagonistic, I genuinely wanted my situation not to repeat itself again.”

Herrera said his experiences have led him to believe that “film school is almost like a microcosm of what the industry is like.”

“We’re not taken seriously in our program. It’s even harder if you’re a woman, and you’re a woman of colour that is a much harder thing to get into because that’s just how the industry works.”

Matuto said her issue was not with specific students or professors.

“I have nothing against the students who got my script, that was totally circumstantial,” said Matuto. “It’s a systemic thing within the faculty and this constant problem where narratives like this, maybe they’re not intentionally being squashed, but at the end of the day it’s impact over intent.”

Leave a Reply