By Jacob Dubé

You might want to disinfect the next water fountain you drink from at Ryerson.

In the last five years, there have been 11 instances of fountains tested over the safe limit for “organic matter” in the water.

That’s according to testing data the The Eyeopener obtained through a freedom of information request.

These tests, conducted by Maxxam, a company that specializes in scientific analysis, evaluated the water from drinking fountains across campus for lead and living organisms.

Only one of approximately 50 fountains tested between 2013 and 2017 surpassed the safe lead limit. But the fountains didn’t fare as well when it came to bacteria.

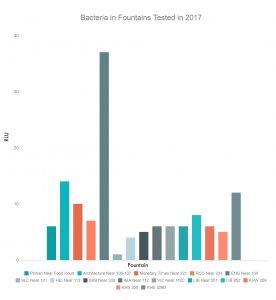

One of the main tests on the fountains measured levels of organic material in Relative Light Units (RLU). That’s a unit of measurement for adenosine triphosphate (ATP), an organic chemical found in all living cells. A high RLU level on a fountain indicates an increased level of organic material on it, like bacteria or fungus, which can transfer into the water a person drinks. A safe level of organic matter is up to 10 RLU, according to the testing data.

At high enough levels, organic material can build up on the fountain and create a visible mould-like substance—that green gunk you’ve definitely seen on campus.

Only two fountains—one in the School of Image Arts Building near room 112, and one in the Victoria Building near room 110C—were tested every year. Seven other fountains were tested in four of the five years.

The water dispenser in the Student Campus Centre (SCC) was tested every year, but the machine was replaced three times—once for failing a lead safety test by double the acceptable limit.

11 fountains surpassed the acceptable levels for organic materials in the last five years

Since fountains are tested sporadically, it’s difficult to accurately track their safety over time, as well as any potential improvements or detriments to the water quality. Some buildings weren’t tested every year, and the number of fountains tested in each building was also not consistent, meaning it’s not possible to take testing data and calculate a campus-wide or per-building average for quality.

In 2016, the water-bottle-filling spout in the Architecture Building was six times over the acceptable levels for organic material at 61 RLU, and a similar spout in the Heidelberg Centre was almost ten times over the allowed amount of organic materials at 98 RLU. A higher RLU level is associated with being dirtier.

Nicholas Reid, the executive director of Ryerson Urban Water, a group that does research and outreach on water issues in urban environments, said testing for RLU isn’t necessarily an accurate portrayal of organic material in water. Simply testing for signs of organic life means you can’t differentiate a harmless cell from a potentially dangerous one.

E.coli is an intestinal bacteria that can potentially cause kidney failure, which Lynda McCarthy, a Ryerson professor specializing in aquatic and terrestrial toxicology, said is a surrogate for looking for fecal contamination in water. When testing for something like E. coli, Reid said a sample has to be incubated at about 38 degrees for one to two days. In that time, any traces of the bacteria will grow and duplicate and can then be identified. Instantly doing an RLU measurement—like Maxxam does at Ryerson—can only identify if there’s any organic material in general.

There aren’t any tests at Ryerson that look for E. coli in the water, according to Alp Amasya, the director of Facilities Management and Development (FMD) at Ryerson.

In their reports, Maxxam indicated workers disinfected the fountains with peroxide and retested until they were at safe levels, but there’s no information as to how long the fountains were that dirty—and how many students drank from them before they were cleaned.

Infographic by Justin Chandler

Jibrahn Patel, a first-year Ryerson biomedical engineering student, started to notice that the water in some of the fountains on campus tasted a little off—sometimes sour, sometimes sweet.

So he looked under one of the plastic fountains at the Student Learning Centre (SLC), and found what looked like mould. “It wasn’t clean,” he said. “That was a little bit unsettling.”

Patel said the worst fountains he’s seen are in high-traffic areas like George Vari and the SLC. “People spit in the sink, or dump their rice or whatever.”

“We’re paying for this with our money, so it should be somewhat cleaner,” Patel said.

Amasya said the water fountains are cleaned daily by a group of 20 cleaners on staff at any given time. Ryerson security has reported people vomiting into fountains before.

“Sometimes, people do other things in them,” Amasya said. “As soon as we notice something like that, we clean them.”

In terms of the lead levels, McCarthy said Ryerson’s levels were very low. Ontario’s acceptable limit for lead is 10 parts per billion (ppb), and the lowest readings in the tests were .5 ppb, which she said is like “one drop in 20 olympic sized swimming pools.”

Yet McCarthy stressed there is no such thing as a safe amount of lead, because it stays in a human body and accumulates over time, which can lead to health and development issues, especially if a person is exposed at a young age.

Typically, lead seeps into water from either lead pipes, which were used in construction until the mid-1950s, and lead soldering, which was used to repair pipes until as late as 1990, according to the City of Toronto. If water stays stagnant, the lead from pipes and connections corrodes into it. Amasya said FMD isn’t aware of any lead connections at Ryerson.

In 2015, one water dispenser in the SCC tested for double the safe amount of lead in drinking water and students weren’t notified

According to the reports, the only time in the last five years a fountain failed a lead safety test was the water dispenser near the first-floor bathrooms in the SCC. In 2015, it tested at double the safe limit, hitting 20 ppb.

If Ryerson finds an unsafe fountain, Amasya said, staff put a sign on it and “lock it out,” while investigating what issues caused the high levels.

In the case of the SCC fountain, the unit was replaced. Amasya also said students should have been notified online. The Eye is located in the SCC but found no record of an email warning our staff or students.

While the levels of organic material continue to fluctuate, the lead levels in the water in Ryerson’s fountains are consistently improving.

A 2014 Toronto Star investigation found 13 per cent of household water tests in the city surpassed the acceptable amount of lead. Homeowners were being held responsible for replacing the expensive lead pipes in their old homes, and some were unable to afford that.

After that investigation was published, the city implemented a corrosion control program—it was also mandatory province-wide—which added phosphate to the water to create a protective coating on pipes.

According to Metro, the lead test failure rate in Toronto dropped from 13 per cent to 1.8 per cent , between 2015 and 2017.

So feel free to take a drink of Ryerson’s water, just make sure you trust the fountain first.

Leave a Reply