It’s no secret that Ryerson is partnered with facilities that conduct animal testing, but details on exactly what the research entails are scarce

By Sarah Krichel

It was about 12 p.m. on March 22 when Paul Bali made his way to the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, a research branch of St. Michael’s Hospital located on the corner of Victoria and Shuter streets. He knelt on the sidewalk with a piece of chalk, and began to write a message in front of the large glass building addressed to the staff members inside.

“Level 8, kill rate?”

The philosophy professor only got to the second word when St. Michael’s security came out and told him to cease and desist. He finished writing the rest of the message, but then the security guard threatened to call the police and have him arrested.

“I thought, I’m not going to break into the lab, just draw attention to it,” Bali says. “Let [the people] know there’s something here that’s problematic.”

Two more security guards then appeared, along with two custodians who tried to wash the message off with hot water. Bali told the security guard he would wait for the police to show, but after 10 minutes, he left to return to Ryerson to make his next class.

When The Eyeopener reached out to St. Michael’s security department to inquire about the incident, an official said they were aware of it but could not confirm details.

The eighth level of St. Michael’s Hospital is where the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute’s vivarium is situated. It is also where Ryerson conducts its own in vivo research, which is any study that is performed on a live organism. It could be anything from plants to fruit flies to monkeys. In the last year, Bali, who has been a professor at Ryerson for about 14 years, has taken various actions to find out more about what animals and practices Ryerson uses in its own in vivo research. But many of his questions remain unanswered, which Bali says lies in strict barriers to accessing any information.

Paul Bali writes, “A mouse will roar” on multiple sidewalks outside the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute on April 2. Photo: Sarah Krichel

In vivo research has been credited for many of today’s scientific achievements, including the discovery of insulin and nerve transplants. Some scholars and scientists argue that sacrificing a creature is a vital step for scientific progress. It can allow scientists to learn the harmful and beneficial effects of a new medicinal practice, by testing those practices on organisms with similar DNA first, such as monkeys, before using it on humans.

Every year, millions of animals in Canada are the subjects of experimentation for scientific achievements. In March of last year, CTV News reported that the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC) investigated undercover footage, obtained by CTV’s W5, which appeared to show “mistreatment of dogs, pigs and monkeys” for scientific research purposes at a Montreal-based institute.

Educational institutions have also been in the crossfire of activists shining light on practices they deem inhumane, like the University of British Columbia, which has its own anti-animal testing collective. At the University of Toronto (U of T), research practices on macaque monkeys made headlines in 2012, when the last monkeys were euthanized after a seven-year brain study.

Despite the lack of media coverage, Ryerson is not exempt from similar controversies, and Bali sees a lack of transparency on Ryerson’s part as contributing to an already extremely controversial practice.

“There’s a lot of secrecy around these things,” he says. “If people could really see what’s going on, I mean really see at the level of the animal … It’s what will change that whole system.”

***

The CCAC is a peer-review organization that sets and maintains standards for ethics in animal research use, such as housing, feeding and euthanization. The council says it works to ensure animal-based research in Canada only takes place when necessary and with high health and safety standards. The organization certifies institutions to conduct research, but has worked with Ryerson instead through St. Michael’s Animal Care Committee (ACC) since 2010.

Both the ACC and CCAC approve of and oversee every research project proposed, referred to as a protocol, by Ryerson faculty members or students. Ryerson’s policy on the ethics of research involving animals was approved by the Senate in 2002, which has a line in the policy stating that every effort must be made to find a substitute for animal use, but where that is not possible, animals must be housed, fed and treated as humanely as capable.

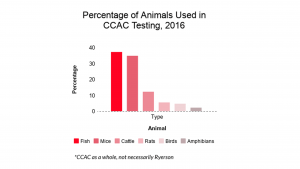

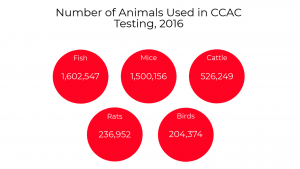

The CCAC publishes a yearly report which breaks down which animals are used, in what ways and for what purpose. In total, under the council, 4,308,921 animals were used for scientific research in 2016, including fish, mice, pigs, dogs, non-human primates (like monkeys) and others. Fish were about 1.5 million of those animals, while dogs were a bit over 15,000 and non-human primates took up about 7,500. The report also goes into the practice, purpose of the research and the level of invasiveness (the level of distress, discomfort or pain that an animal goes through during testing). The CCAC does not account for all animal science research in the country. It is unclear which animals of those belong to Ryerson research. The CCAC does not publish information on protocols, species or number of animals used by Ryerson specifically, or any other specific institutions.

The Eye spoke to Jennifer MacInnes, Ryerson’s senior legal counsel and senior director for applied research and commercialization. MacInnes oversees the university’s issues around intellectual property, research compliance and integrity as well as the ethics portfolio of Ryerson. She said approximately 20 Ryerson research protocols involving in vivo research are approved to begin or continue on an annual basis by the ACC.

The Eye spoke to Jennifer MacInnes, Ryerson’s senior legal counsel and senior director for applied research and commercialization. MacInnes oversees the university’s issues around intellectual property, research compliance and integrity as well as the ethics portfolio of Ryerson. She said approximately 20 Ryerson research protocols involving in vivo research are approved to begin or continue on an annual basis by the ACC.

MacInnes said she could not speak about any specific ongoing project or details referencing Ryerson’s protocols. “It’s because the nature of the research they’re doing kind of indicates what the research is about,” MacInnes said. “I’m not going to talk specifically about which animals we do research on.”

Ryerson cannot disclose such details on its in vivo research protocols due to its Information Protection and Access Policy, which states that the university is “committed to protecting specific types of information, which, if disclosed, could reasonably be expected to result in harm to the university, an identifiable individual or a third party.” It also states that since 2006, the university is subject to the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA). While the Act is in place to ensure public institutions’ transparency, one of its sections states that it does not apply to records pertaining to research of an employee or associate of an educational institution.

When The Eye asked Ryerson president Mohamed Lachemi about the suggested lack of transparency, he redirected us to MacInnes’ department for further comment. The department, which is called the Office of the Vice-President, Research and Innovation, responded that they “don’t have anything further to add.”

While there isn’t animal testing physically on Ryerson’s campus, MacInnes confirmed with The Eye that Ryerson’s in vivo research takes place at St. Michael’s Hospital, including the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, the Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science, as well as Sunnybrook Hospital. But the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute redirects any Ryerson-related questions to Ryerson staff.

Bali says he acknowledges all of the accomplishments animal testing has provided throughout the years, but believes that an increase in transparency of institutions like Ryerson can allow for future policy changes. “Things are the opposite of how they should be. Researchers have the protection of anonymity, and the animals have no protection whatsoever.”

While Bali knows the road ahead to stopping animal testing is a long one, he hopes to at least shed some light on the practices that take place. “Awareness does change a lot,” Bali says. “It’s because people are pretty decent. If they really know what’s going on and see the connections between their actions and these systemic violences, [it can] stop. Things can change.”

***

In 2012, Paul York, an animal ethics and religion professor at U of T, pinned up posters on his campus that read: “I’m interested in saving any animals you’ve done experiments on. I’ll give them a good home. If you’re interested, contact me.” He received an email from a graduate science student who said they had eight mice from a cancer lab, and York agreed to pick them up.

When York went to the U of T lab to pick up the genetically engineered mice, he saw one of the scientists injecting another group of mice with a disease. The graduate student came out and handed him the mice, and York left the lab to take the mice home. They were “cute little guys,” all white, with black eyes. Two weeks after York took them home, the first of eight mice died—it had a tumour on his back. After six months, they had all died.

“There was really nothing I could do for them,” York says. One, he says, died in his arms, trembling as he pet him. York realized then that rescuing sick animals doesn’t work. “Once they’re created in a lab, it’s actually more humane for them to die in the lab than to be rescued. So I never did that again … Once you’re genetically engineered for a lab, your [fate] is sealed.”

Animals that have been tested on will usually face euthanization after being bred in human captivity. A common way animal rights activists try to stop this is through rescue missions, such as York’s, or the five graduate students who tried to save the two macaque monkeys that U of T was going to euthanize in 2012. But it was too late, once they realized they had already been killed. U of T’s been in a controversial spotlight for many years for its animal testing practices. It also follows the ethical guidelines of the CCAC.

Animals that have been tested on will usually face euthanization after being bred in human captivity. A common way animal rights activists try to stop this is through rescue missions, such as York’s, or the five graduate students who tried to save the two macaque monkeys that U of T was going to euthanize in 2012. But it was too late, once they realized they had already been killed. U of T’s been in a controversial spotlight for many years for its animal testing practices. It also follows the ethical guidelines of the CCAC.

But York claims that the entire industry is “purposely non-transparent.” He thinks that if people were able to know and see what happens behind closed doors, there would be public outcry.

“If you go around to U of T or Ryerson, and ask the average student, ‘Did you know that there’s animal testing?’ most of them don’t even know it’s happening,” York says. “They’re shocked to find out. That’s one veil of secrecy: the ignorance of it.”

Anna Pippus is an animal rights lawyer and the director of Farmed Animal Advocacy at Animal Justice, who co-published an opinion piece in The Varsity with York on the scientific case against animal research. Back in 2011, she issued a FIPPA request asking for all records of approved animal research by the university in 2010, including animal types and levels of invasiveness. She also requested funding amounts and sources.

U of T responded citing section 65 (8.1) of the Act, which states that her FIPPA request doesn’t apply to records to do with research of an employee or associate of an education institution. But U of T granted Pippus access to most of what she asked for anyway. The funding request was denied unless she paid a fee of more than $3,000 for the amount of hours put into collecting the information. The Eyeopener obtained the FIPPA response from U of T which indicated that U of T’s animal research in 2009 was made up of 58 per cent mice, 22 per cent rats and 14 per cent fish, among others.

FIPPA requests at Ryerson haven’t gotten nearly as far. On Feb. 10, 2017, Bali issued a FIPPA request, asking for numbers, types, methods, purposes and invasiveness levels of Ryerson’s in vivo research. The Eyeopener also issued a FIPPA request for any records on animal research conducted by Ryerson, numbers, nature of tests and purpose of research on animals, as well as Ryerson’s partners and locations. Both Bali’s and The Eye’s requests were denied, with Ryerson citing the same research privacy clause that U of T cited in theirs. The Eye’s request for information on funding was flat out denied.

Heather Driscoll, who oversees the university’s response to FIPPA requests, told The Eye that responses are always in compliance with two main things: an individual’s right to request information from a public institution, as well as protecting individuals’ personal information. Driscoll says this section also seeks to protect personal information of the researchers. “We want to make sure there’s no harm that’s going to result if we disclose the record.”

In The Eye’s and Bali’s request, the denial also referenced subsections of the Act that speak to the endangerment of life or physical safety of a person, as well as the security of a building.

“Driscoll is just doing her job,” Bali says. “I don’t expect a conspiracy, it’s just been set up to protect these researchers. It’s pretty ridiculous.”

***

After months of research, I decided to see things for myself. I pressed the level 8 button inside the elevator of the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute and was taken to the top floor. Stepping out of the elevator, I saw stark white walls hanging modern paintings. Employees walked around looking important with badges to get through thick doors that shut loudly behind them. It was a calm, quiet building that made me feel like I was somewhere I wasn’t supposed to be.

The building where the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute is housed. Photo: Sarah Krichel

As I walked around pondering what could possibly be going on in this place, I finally found one door marked “vivarium,” which is a type of lab where in vivo research is conducted. All I saw through the small window were glass tanks piled on each other, containing green plants, a hallway leading further into the lab and another unmarked grey door. The only movement I saw was a scientist in a long green lab coat and matching hair cap, who swiftly came and went around the corner.

I searched for somebody to potentially let me into the lab, or to show me where Ryerson conducts its research. Three different people I talked to said I needed one of those white badges everyone was carrying. The last guy told me it’s “pretty locked up,” and that’s when I gave up.

I came with questions and I left without answers. As long as institutions like this prioritize privacy over transparency, we may never know what goes on behind closed doors.

Erika Ritter

Kudos to Sarah Krichel and the Eyeopener for this piece on the secretive world of animal-based research, much of it conducted by university departments, either on or, as in Ryerson’s case, off-campus. I think it’s especially important for the public to know how non-transparent the CCAC (Canadian Council for Animal Care) is and how woefully low their standards of animal welfare, well-being and cruelty-prevention are. I hope this article provokes not only conversation but action on the campus

Deborah Chalmers

Thanks for tackling this difficult subject. The secrecy surrounding animal testing in Canada is almost impenetrable. We need articles like this to help us begin to see what goes on behind those locked doors.

Audrey Adelyte

This is ridiculous. Three security guards felt it was necessary to leave their important positions within the hospital to tell some guy to wash chalk off the sidewalk? And then they were going to call police come and get the protester to stop writing on the sidewalk….with chalk that will wash off with the next rain? I’m sure the guards were just doing what they were told to do, but what a waste of resources. I work in a big hospital downtown (not St. Mike’s) and I think we’ve got 4-5 guards on at a time. We actually need them IN the hospital for ACTUAL security threats. Staff get physically assaulted all the time.

Just shows you the lengths society will go to in order to avoid dealing with our unethical treatment of animals.