By Sonia Kuczaj

Like thousands of Canadian from across the country, 57-year-old Joaxquim Teotonio travelled to Ottawa five weekends ago to say farewell to the prime minister he admired more than any other. In Parliament’s Hall of Honour, he waited patiently in line for four hours to pay his last respects. Having immigrated from Portugal 38 years ago, Teotonio felt he shared a special bond with Pierre Trudeau, the man whose policies opened the country’s doors to immigrants and ushered in an era of multiculturalism that continues to reshape the face of Toronto.

“Trudeau meant a lot o me personally,” Teotonio says. “Not just an important prime minister, he brought the people of Canada together.”

Today, Pearson International Airport is the major port of arrival for the country’s immigrants, making Toronto one of the most multicultural cities in the world. The city of 4.3 million is home to approximately 1.8 million immigrants, nearly one quarter of the country’s total number immigrants. Since 1961, the number of visible minorities in Toronto has risen to 37 per cent from 3 per cent, and within the decade, there will be more visible minorities than white people living in the city.

All this change, however, is not accurately reflected in the city’s political offices, media, school boards and other institutions. Immigrants like Teotonio tell stories of isolation, discrimination and hardship intertwined with some successes. Their tales mirror the experiences of hundreds of thousands of other immigrants in Toronto. How well the city deals with its ever-changing landscape will depend largely on how well it listens and learns from the experiences of such immigrants.

Teotonio moved to Canada at the age of 19, settling in Toronto. He left Portugal because he did not want to serve in the Portuguese army for political reasons. Luckily, he had someone in Canada who could sponsor him, his older brother, Jim, who had immigrated to the country a few years earlier.

Teotonio has seen the city change tremendously since he moved here. “I saw more immigrants coming in. Now you see people with the same needs,” he says. “Changes made me feel more comfortable. You are not just an alien. You have a sense of belonging to the country. You feel like you have a place of recognition.”

The immigrant from Portugal who arrived in Canada penniless has come a long way. Today, Teotonio works as a tax assessor and lives with his wife and three kids in a house he built himself in Mississauga. He is also a graduate of York University, where he completed a degree of Canadian studies in 1997.

Teotonio has adjusted well to Canadian life, but he believes too many immigrants continue to encounter discrimination. That was the case in 1975 when he was hired as a statistician for the city’s police department. Teotonio says his co-workers looked at him funny because he was the only non-British immigrant working there. He also found he was always being given jobs the others didn’t want to do.

While today about half of Toronto’s residents are immigrant, Teotonio’s ancestors would have had an impossible time trying to enter the country. The city’s doors were basically shit to immigrants before the 1950s. Only small groups of newcomers were allowed to live in Toronto in the early 1900s. Although they never truly became part of the community and were tolerated as long as they stayed in enclaves such as Kensington Market.

The end of the Second World War changed all this, as it spurred an economic boom and created an abundance of industrial jobs that gave Canadians a sense of financial security. Before the 1950s, most jobs for immigrants involved agriculture.

In 1952, Canada adopted an urban-friendly immigration policy that allowed newcomers who wanted to live and work in the city to enter the country.

The policy prompted the emergence of a new ethnic pluralism in Toronto, but, like others before it, the policy was not without its biases. While it was less ethnically selective than previous immigration laws, it still discriminated against groups such as blacks and Asians by allowing few of them into the country.

In 1971, then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau introduced multiculturalism as a federal policy — a new respect for cultural diversity was born. But it wasn’t until 1976 that revisions were made to the 1952 immigration policy, most importantly the abandoning of racial and ethnic discrimination.

Under the new act, refugees for the first time were allowed to immigrate to Canada. It also opened the door to immigrants from the West Indies and Asia.

Tien Providence is one of those immigrants. He arrived in Toronto 11 years ago from St. Vincent with a dream of establishing a writing career.

Although Providence had family here to help him when he arrived, he felt they didn’t understand his aspirations to be a writer. “It’s a major economic situation if you come with dreams of being an artist,” he says. “A lot of older immigrants dream of a better life, basically a better material life. A writer isn’t considered a job.”

Since immigrating to Toronto, Providence has written three plays and is now writing a novel depicting the life of a young boy in St. Vincent. He says he’s seen the government move from the left to the extreme right and feels society has correspondingly turned meaner. When problems such as high unemployment arise, he finds residents are quick to blame immigrants.

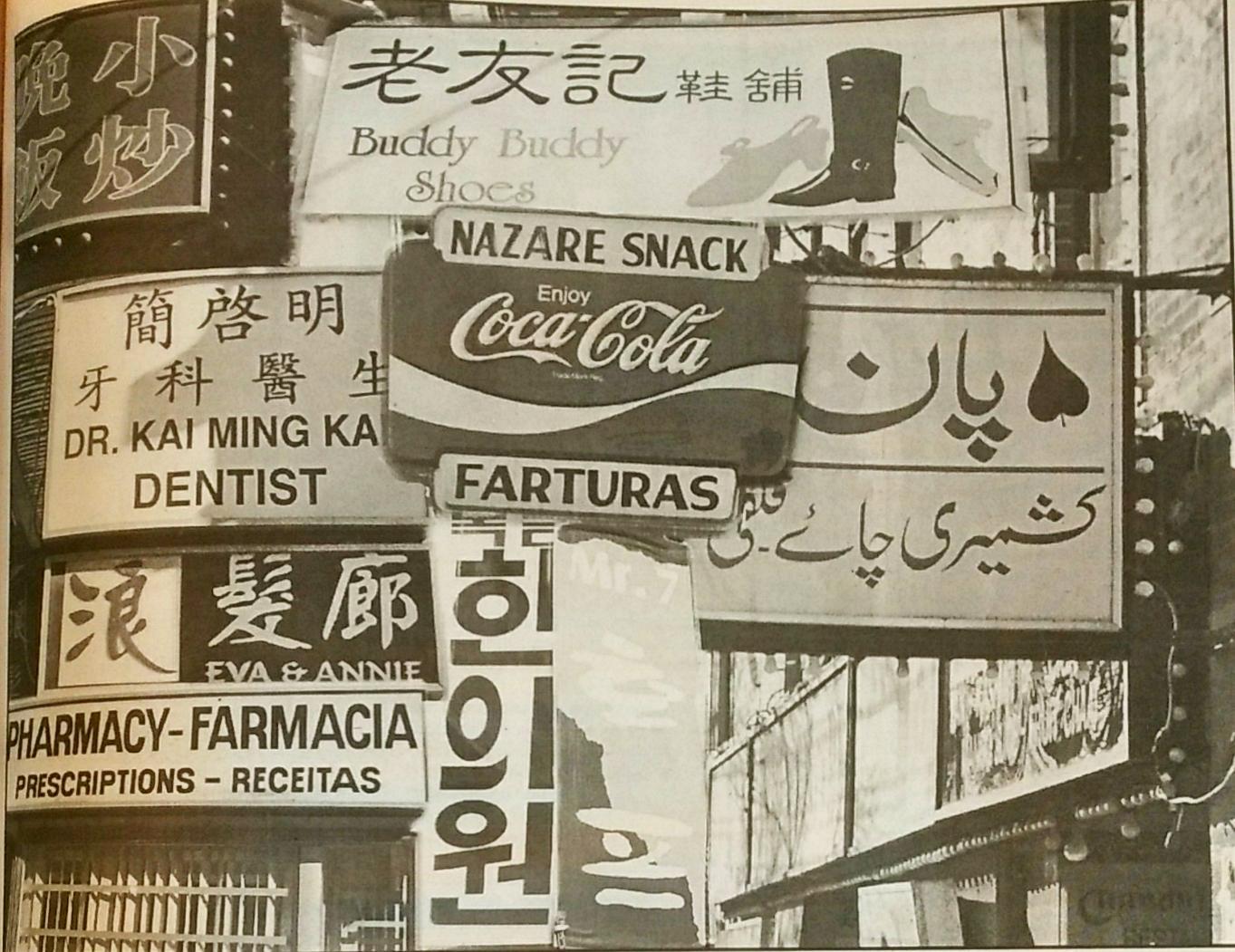

“Toronto is a safer place in terms for the type of life I like to lead,” says Providence, who plays host to a jazz show on Ryerson’s campus radio station, CKLN. “I like to walk, no restriction to where I want to go. You can walk through Toronto and walk to one country to the next,” he says of the city’s cultural communities.

But these days people new to the country are more likely to move to highrise apartment buildings than to neighbourhoods that represent their ethnicity, while long-time immigrants prefer home in the suburbs.

Moreover, places such as Little Italy and the Danforth, once havens for cash-strapped Italian and Greek immigrants, respectively, have become trendy spots to live and hang out for middle and upper class. In turn, the real estate prices in these areas have skyrocketed, making rental too expensive for new immigrants.

Providence says his involvement in CKLN and local theatre has helped him feel a part of the city. This isn’t the case for 36-year-old Janet Baez. Seven years after immigrating to Toronto from the Dominican Republic, she still feels like an outsider.

“You never see your neighbours. It’s not easy to make friends. It’s like no one trusts anyone here.”

Baez, who worked as an elementary school teacher in her homeland, moved here on the advice of her mother, who lives in Toronto. Things haven’t worked out as she hoped, though. Today, she works in Ryerson’s Hub.

“My mother told me it is better here and to come,” she says. “But unlike myself, my mother had no education in the Dominican Republic. For her it was easier to accept starting over with nothing. For me it’s a broken heart, my whole life.”

These are issues Toronto must confront head on as its immigrant population swells. If immigrants continue to feel as if they don’t belong, the city’s future health will be jeopardized.

“I’d anticipate tensions and difficulties,” says Ryerson politics professor Myer Siemiatycki. “A lot will depend on whether newcomers will think that their identity is recognized.”

In his paper entitled Immigration & Urban Politics in Toronto presented to an international metropolis conference in 1998, Siemiatycki noted: “The policy field that has frustrated more immigrant communities in more municipalities across the GTA has been land use planning.” He uses the Jamaican community to feel it was not a welcome part of Toronto.

Another cause for tension among immigrants is the lack of representation visible minorities have in municipal government, the media and other institutions. Michael Doucet, a professor with Ryerson’s school of applied geography, believes many of Toronto’s institutions lag behind reality, even though most of them profess to embrace multiculturalism and often use it as a selling point.

“We will know Toronto has arrived when the bid for the [2008] Olympics is headed by any other group than just three white males,” Doucet says.

University of Toronto philosophy professor Joseph Heath is confident the city will someday accurately reflect its cultural makeup. He says institutions are starting to change and will in time reflect the diversity of Toronto’s population.

“Right now there may be a certain amount of tension,” Heath says. “Senior bureaucrats in City Hall and universities were hired 40 years ago. They represented Toronto as it was when they were hired, bot Toronto as it is today.

“It will take time to change. It is a change that is already taking place within the junior faculty and the student population.”

Leave a Reply