U SPORTS NOW LETS ATHLETES PLAY WITH EITHER THEIR ASSIGNED SEX OR THEIR GENDER IDENTITY TEAM, BUT THE RIGID GENDER BINARY STILL DOMINATES SPORTS CULTURE

By Max Lewis and Sarah Krichel

Growing up, Goldbloom was one of those kids who was active at all times. They were never amazing at sports, but loved playing them nonetheless. They started with swimming, dance and cheerleading, and later moved on to fencing. Now, the fourth-year film student is turning their passion for the sport into a film, focusing on something rarely talked about: the way the gender binary dominates sports.

The film, entitled Parry, Riposte, written and directed by Goldbloom, is about a team of four fencers who arrive to their studio to find it destroyed. “Tranny” is written across the wall, and the fencers realize they’ve been victims of a transphobic hate crime. “It’s a poignant way to destroy the studio, because it inhibits them from actually competing more,” Goldbloom says. The film is being produced by a team entirely made up of trans individuals and will premiere at the Ryerson University Film Festival in May. “I think a lot of stories with trans people are very much like trauma porn for cis people. This film tries to talk about hate crimes in terms of what effects it has on the victims.”

The hate crime did not happen to Goldbloom, but the film draws upon their experience as an athlete who is trans, non-binary and queer. Goldbloom chooses to compete in the women’s division due to the fact there is no non-binary team, creating a polarizing environment.

Last September, U SPORTS, the national governing body of Canadian varsity athletics, announced a new inclusive policy for transgender athletes. It states student athletes are now free to compete on the team that either corresponds with their sex assigned at birth or their gender identity. It does not require student athletes to go through hormone therapy to compete with the gender they identify with.

The policy was developed by an equity committee of representatives from U SPORTS. They were guided by a 2016 report by the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES). The report consulted various sports experts—but fewer LGBTQ2A+ experts—and covers topics like inclusive policies, practices and sex and gender education.

The report did consult trans individuals in its formulation, but Megan Cumming, corporate communications manager for the CCES, could not confirm whether any individual on the expert working group is trans themselves.

Previously, there was no policy directly related to trans athletes’ capacity to participate within varsity athletics on the team of their true gender identity. This led to the exclusion of Jacob Roy, a transgender man, who was barred from participating in varsity athletics at the University of New Brunswick Saint John as well as St. Thomas University because coaches and administrators were unsure of where they thought he belonged.

In sports, transphobia persists because of the focus on the binary. “I think about the history of sport for the first 100 plus years of sport, as we currently understand them, women weren’t allowed to [participate],” says Andrew Pettit, Ryerson’s recreation manager. “Sports was a men’s domain and that was a problem of sexism, at one point across history they started to allow women to take part. That brought forward a binary that really amplified the role of gender in sport in an unnecessary way.”

Issues like these are the obvious gaps Goldbloom highlights—non-binary, non-gender-conforming and genderqueer athletes may not identify with either team, giving them no space to play within a team they’re comfortable with. “There’s only two gender categories. What, for example, if you’re a trans feminine person or trans masculine, but you pass—where do you fit in in those spaces?”

Chair of the equity committee Lisen Moore says that once it was given the mandate to develop the policy, an exhaustive, two-year process ensued, involving CCES representatives who had a hand on the the 2016 report and experts from the Canadian Anti-Doping Program (CADP).

“We needed a policy to address a subset of our student populations that weren’t free to benefit from that experience [of sport],” says David Goldstein, U SPORTS’ chief operating officer.

In September, The Eyeopener reported that comparably, the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s (NCAA) policy in the U.S. allows trans women to compete for men’s teams, but won’t let those athletes play for the women’s team unless they take hormone treatment for a full calendar year. Trans masculine athletes undergoing a hormonal treatment aren’t allowed to play on the women’s team unless the team’s status is mixed.

Like all other student athletes, trans athletes are limited to five years of eligibility, and allowed to compete with one gender team during the span of an academic year. In a University Affairs piece from January by Shireen Ahmed, Roy also pointed out that “no transgender or queer individual’s experience is identical and that an athlete’s gender identity may not remain the same over the school year.”

At the recreational level, gyms and change rooms can present a dangerous environment for trans folks. Ryerson has made some progress in recent years for trans safety and inclusivity. In 2014, the school implemented “women’s only” hours at the Recreation and Athletics Centre, but the Mattamy Athletic Centre still does not have any women’s only hours. Pettit says that non-binary, genderqueer and gender diverse people are also welcome at women’s hours, “primarily knowing that members of those communities have also been marginalized in sports, and have experienced violence in the broader community.”

Goldbloom says schools supporting trans athletes starts with dismantling misogyny, through acts like calling out transphobia, misogyny and racism when you hear it within your circles. If you’re a coach, it’s your responsibility to be a role model at every turn: “Not just being a role model for young boys and girls, but anyone else whose gender is not those two things.” On top of that, don’t ask about someone’s sex or gender behind their back—ask the individual directly. “Equity training on sports teams is so so needed and it’s not something that people consider.” For reform to happen, Goldbloom just hopes people will want to take up these recommendations, instead of just dismissing the “loud trans kid, talking about shit that’s never going to happen.”

“There’s a way to do sports and be respectful of your teammates, and have open space,” Goldbloom says.

But Goldbloom points out a bigger issue in the sports industry at large. Without dismantling misogyny, let alone transphobia, policies won’t do much to change the way trans athletes can exist in the university.

“At higher levels such as the Olympics, they put rules on athletes demanding they have certain surgeries or have a number of years under certain hormones, but that’s policing someone’s body,” Goldbloom says. “You’re telling people they have to be a certain level of trans in order to cooperate in your system.”

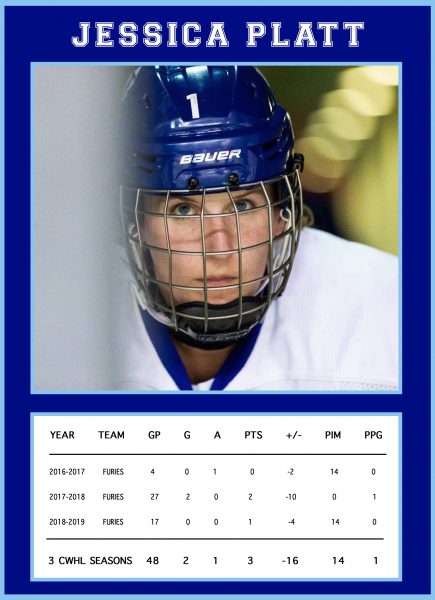

Jessica Platt’s introduction to hockey was not unlike many other young athletes: skating on an ice rink in her backyard in Sarnia, Ont. The game was ingrained into her at an early age, fostering a passion that would lead her to the Toronto Furies of the Canadian Women’s Hockey League, the highest level of female professional hockey.

At 19, Platt quit hockey for mental health reasons and decided to pursue schooling. While at Wilfrid Laurier University, she learned how to go about transitioning.

After graduating, she joined a local recreational league. Two years later, she achieved a permanent spot on the Furies. The journey was “unexpected, but awesome.”

When Platt is on the ice, she wants to let her playing do the talking, but being the only transgender player in the league gets in the way. “I want things to be easier for people coming after, I don’t want them to have to hear the kind of things I heard growing up, and get treated how some people have negatively treated me on the internet,” Platt says. “That being said with all the negativity, [the experience] has been overwhelmingly positive.”

She remembers what it was like in the men’s locker rooms, hiding who she was to protect herself from harassment. Although she believes that generally, people today are more accepting. Due to the fact that growing athletes are often in an educational environment, people are “willing to learn,” but being actively involved with initiatives and groups that promote that education are even more important.

Currently, U SPORTS is working on a document that works toward that education; it’s about best practices and recommendations that will be issued to its member schools, detailing procedural issues such as locker room access, how to support and cheer for your teammates, useful announcer messages during games and breaks of play, and increasing awareness for coaches and administrators about trans athletes and issues the community faces.

Platt says that all in all, it’s important that the policy exists—even if it’s just a document, and not necessarily an all-encompassing societal step forward. “It’s important to see the legislation being written so that trans athletes feel welcome,” Platt says, adding that trolls will always say trans athletes don’t belong in sports. “So having the press release, having the policies, having everything written there just reaffirms that they are accepted, they are included.”

A clause high up in the new U SPORTS’ policy states all athletes must comply with the Canadian Anti-Doping Program (CADP). This has important implications for trans athletes in post-secondary.

The CADP is provided by the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES) and is the administrative body that regulates anti-doping and fair sport practices. They also develop online modules and courses to educate incoming athletes on the current list of prohibited substances, and administer drug tests at selected intervals during the season.

The CCES’ selection of athletes who are tested is randomized across all varsity sports in Canada. The centre can choose the women’s volleyball team, for example, and select any team member arbitrarily to give a urine and blood sample for testing.

According to the report’s section on understanding policy on hormone therapy, only 30 percent of surveyed trans individuals in Ontario were not using hormones. This stat alone shows the sheer amount of athletes affected by regulations around hormone therapy—allowing trans players to participate in sports, regardless of where they are in transitioning, can play a huge role in their ability to be included in sports at all.

A common misconception is that trans people would make their decision to transition motivated solely by a physical advantage. “It’s an uninformed, ignorant way of thinking,” says Pettit, emphasizing the threat of violence and discrimination that would come with such a decision. The National Women’s Hockey League developed the first cohesive policy to welcome Harrison Browne, the first openly trans athlete in North American pro hockey. But he isn’t allowed to physically transition, as the hormone therapy would disqualify him. Goldstein says samples collected during a test are compared with what is scientifically considered the normal range of testosterone for a male or female. For example, a transgender woman who was formerly male would almost certainly test over the normal range of testosterone compared to a cisgender woman, generating a result that implies culpability of doping.

Another way it would come up, Goldstein says, is if an athlete in the process of transitioning is taking substances to aid the process. That would flag a violation in the CCES testing.

In these events, student athletes have two options to clarify the reasoning for their results. U SPORTS may use Therapeutic Use Exemptions, which athletes apply for in advance of testing for official permission for the medicine. The method they most commonly use, however, is a medical review, which clarifies hormone therapy after an athlete tests positive for doping.

Megan Cumming, corporate communications manager for the CCES, confirmed to The Eyeopener that an athlete who is still in the midst of acquiring proof of their hormone therapy wouldn’t be suspended from playing. That may only happen, Cumming says, if there is an abnormality with the way the athlete is engaging with the process, or if they ignore it entirely.

On top of that, Goldstein points out that the concept of hormone levels impacting athletic performance isn’t directly supported by scientific evidence. “The CCES felt that to require an individual to undertake hormone therapy or surgery in order to protect the level playing field would be forcing someone to undertake an invasive medical procedure.”

In fencing, the mind needs to be sharp and focused for a game. If it’s not, it’s near impossible to fence, Goldbloom says. But you can’t stay sharp when you’re thinking about someone who misgendered you two seconds ago, and you’re constantly questioning where your gender fits into an athletic space.

The story of their film Parry, Riposte revolves around how that experience affects the game. Sports are always about ‘getting back up again’—but Goldbloom says sports narratives often don’t represent how mental health impedes on that. “That’s why I think ‘just do it,’ is bullshit. Sometimes you can’t ‘just do it,’ because you’re depressed.”

With files from Alexandra Holyk.

Leave a Reply