By Liz Nyburg

Customers of the Royal Bank and the Bank of Montreal won’t be voting on whether the two banks should merge. Only bank shareholders get to do that. But Metro Credit Union, a different type of bank, is having a members meeting on Feb. 19 to vote on a proposed merger with Jet Power Credit Union. As Donald Altman, chair of the board, writes in a Metro newsletter, “It is up to you to make this important decision.” It may not sound like radical politics, but it is. Metro Credit is a bank but it doesn’t aim to make a profit.

The credit union is a consumer co-op bank and like most co-ops it’s nonprofit. Co-ops were born among poor folk and still have a social conscience. They’re member-owned, so if you don’t like the way your co-op is tun, you can go to a members’ election meeting and vote in a new board of directors. Your vote will count as much as the next member’s no matter how much money you have invested in the co-op — someone with $43 in their account gets one vote just like someone with $43,000. You can even run to be a director.

Co-ops don’t have outside shareholders anxious for dividends. Any surplus is turned over to the members or used to improve the co-op. The members at Windmill Line housing co-op keep rents reasonable and put any surplus into better building maintenance. Bread and Roses, another credit union, sometimes offers a better rate on its term deposits than the big banks. Karma, a co-op food store, recently used its surplus to buy a new produce cooler.

There are co-op for all sorts of things and they’re not only more socially conscious, they can save you money. Here’s how.

What about money?

Credit unions like Bread and Roses and Metro Credit Union (which has a branch in Jorgenson Hall) are consumer co-ops which offer most banking services. You can get savings, chequing and term deposit accounts. Bread and Roses doesn’t loan money but Metro does (although they don’t do student loans you can cash your OSAP cheque and deposit it at any credit union). You get an Interac bank card just like any other bank.

To join you just fill out the usual forms and put money in your membership share account. At Metro, they want you to put $25 each year toward your membership share up to $150. You get the money back if you leave the co-op and they pay a dividend. Last year it was five per cent. You can start putting the rest of your fortune into chequing and savings accounts right away. There is no work requirement. Nonetheless, you can vote for directors and participate.

Wanna eat?

Most Toronto food co-ops are actually clubs where members order food ahead of time rather than walk into a food store. For harried students, Karma Co-op (with about 1,000 members) is a useful exception. You can “trial shop” at its Annex store once before joining.

The mark-up on things like organic fruit and biodegradable detergent is reasonable. Nonetheless, Karma buys a lot of whole food as well as name brands, so you won’t find Price Choppers-style bargains. At Karma you pay $70 to join, then $16 a year. You can join as a “non-working” member, and pay a slightly higher markup. Or save money and work two hours a month as a cashier, cleaner, restocker, newsletter contributor or committee member.

Need clothes?

You can buy jackets, backpacks and boots (not to mention crampons for climbing the Jorgenson escalators) at Mountain Equipment Co-Op. It’s part of a million-member Canadian co-op founded in 1971 by a dew wilderness-loving Vancouverites. Membership is five dollars and thee is no work requirement. Even so, it’s non-profit and you can vote for directors by mail.

How about a car?

Quebec City, Montreal and Vancouver already have car co-ops. Liz Reynolds, a housing co-op veteran, is starting AutoShare this spring in the Annex and Riverdale neighbourhoods of Toronto.

If you join, you’ll be given a phone number to reserve a car when you need it, and they ket to its special lock box. Then you’ll go to the car (parked in your neighbourhood), take the car key from the lock box and drive away. You’ll write down your kilometres and time in a log-book in the car and return it when you’re done.

Unlike a car purchase, you won’t be tempted to drive the co-op car just because it’s sitting in your driveway. And unlike a car rental agency, AutoShare won’t make you stand at the counter filling out forms every time you want a car. You’ll be able to book the car for as little as an hour. You’ll pay $500 to join (refundable if you leave). You’ll be asked for a driving record check. Then AutoShare will bill you monthly for your share of maintenance, gas and insurance based on the hours and kilometres you drive.

Need a place to stay?

Suppose you want to try a housing co-op. You apply to join, then go for an interview with the member selection committee to convince the co-op you’ll be a good neighbour. If you’re accepted you become a voting member of the co-op and move in. There is no single landlord. You and all the other members are the landlord.

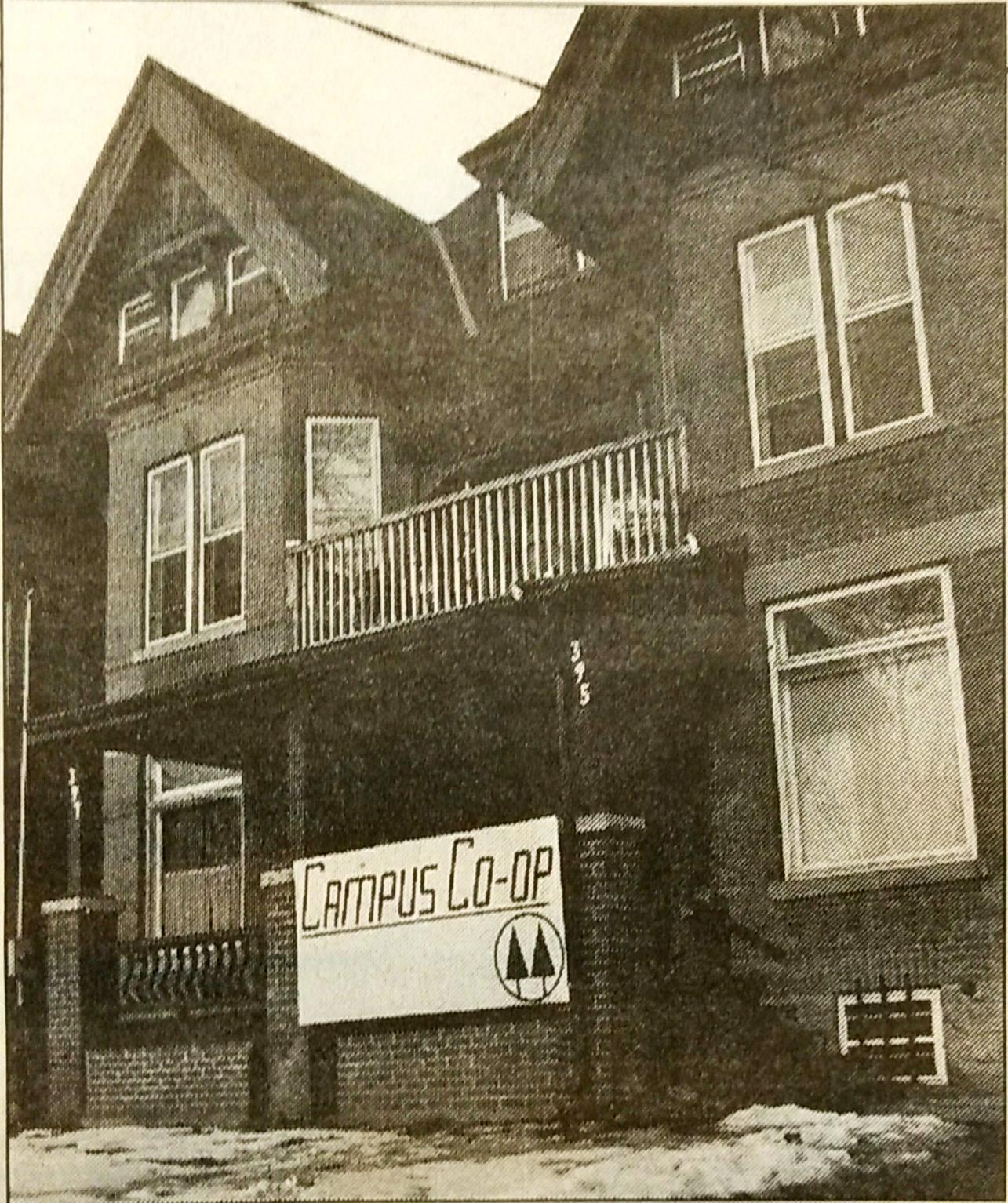

Mary Kempton, a Ryerson graduate and director of Campus Co-op, lives with 15 graduate students in one of many big old houses the co-op owns near the University of Toronto. She’s paying $425 plus $70 utilities for a huge room.

Ryerson aerospace engineering student Sean Kloosterman is paying $353 a month for a room at Neill-Wycik co-op. He shares a kitchen and bathroom with four other students. Last year he paid more and got less. He rented an apartment with a friend and paid $400 for his half on a one-bedroom. “We built a wall with milk crates and a shower curtain for the door.”

Ask about work requirements when you join. Some housing co-ops hire staff to manage the property, but many require members to help too. At Campus Co-op, Kempton does eight hours per term painting or restoring, plus eight hours per year committee work. Since she’s on the board, she puts in 20 hours per week. “I quite love it,” she says. “It’s cheesy but true, I love the spirit of cooperation and sharing.”

Neill-Wycik member Kloosterman, on the other hand, has to comply with a new, two-hours-per-month community-oriented work requirement, which is still controversial. “People didn’t mind if they were saving money, making everyone do maintenance, but force people to hang out together?” For now he sets up a movie night every month on his floor.

Once you’ve joined a consumer co-op it’s logical to see the advantages of the co-operative movement. Cockroaches may disagree. I moved out of Windmill Line co-op years ago but called the other day to check. General manager Peter Dewdney said cockroach activity was “fairly minimal.” Maybe they prefer privately run buildings.

Leave a Reply