By Kenny Yum

The Senator diner is a bleakly lit small-town restaurant located in the fringes stuck between the Salvation Army building on Victoria and Dundas and across the street from the lavish Pantages theatre. The Senator’s hours of business rotate with the breakfast and lunch crowd of blue collar workers, students and artists, intertwined with the more well-connected theatre dinner crowd.

It is at odds with an area so ragged with decay, left by the city and by big businesses to fend for itself. It is the personifications of what Yonge Street used to be — a pedestrian-friendly, vibrant heart of the city. Somehow, in the past 30 years, the intersection of Yonge and Dundas has lost its charm, its ambiance sucked away by the Eaton Centre, a fortress of retail opportunities.

Bob Sniderman, a self-dubbed restaurateur, has been running this little diner for 14 years. Sniderman is a hands-on owner, feeling most at ease, it seems, at the front of his restaurant among his customers and staff.

At 50, he is a younger, leaner and less gregarious version than his famous father, Sam Sniderman — the godfather of the Canadian music-selling business, better known as Sam the Record Man.

But Bob is his own man, one that struck out of the family business and into the competitive world of cuisine. On a recent morning, with his black cap, black turtleneck, jeans wrapped around a dark cotton knee length coat, he seems incognito. As he sits down for an interview about an area that he and his family has such a huge stake in, Sniderman admits that he’s not a public man. But he is a man with a vision, one that looked beyond his own affairs to help rebuild a street back to its former glory.

With Sniderman helped form the Yonge Street Business and Residents Association (YSBRA) in 1995, he and the association set out on a quest to change Yonge and Dundas — the corner of main street and main. It would not be an easy task: The association faced property owners who clung to their land, a slew of corporate types who were unwilling to come back to the area, and a city that had failed to prop up its core. But the association succeeded. It initiated a development that it says will create a Canada’s Times Square, a clean, bright, and bustling centre of the city, the country. YSBRA formed an innovative alliance of private and public interests who pushed the project with barely a voice of dissent.

But Sniderman, a champion of the street, faced criticism for being too involved, and was accused of benefiting from it, despite his good intentions. In the past year, he was hit by allegations, pickets and protests that hurt his business — an unlikely reward for someone who at one time called himself the ‘conscience of the street.’

The end product of his association’s quest is the Yonge-Dundas redevelopment. This is how they got there.

Our city’s heart has been clogged of late, suffering from disease. Although it is a busy core, with an estimated one million visitors streaming through its arteries each week, it is also a dangerous one. For a one-mile radius, made up of dark alcoves and unlit alleys, Toronto police peg this area as the highest crime zone in the city — about three arrests are made each day.

Yonge Street’s critics often point to the Eaton Centre as the culprit. Business owners know that during the winter months, consumers are drawn indoors and underground. About 80 per cent of the retail in the core strip resides in shopping malls. When Eamon Kelly, the Centre’s general manager, started his job in 1996, he walked the street and was amazed by the amount of pedestrian traffic the street produced, but saw how shady the street’s east side was.

On the east side of Yonge street, a couple dozen dollar stores nickel and dime the strip from Queen to College. There are also sex shops. Arcades. A few fast food joints. An odd electronics store. An eclectic array of loud signs and tacky storefronts. The lighting north or south of Sam the Record Man, topped by hundreds of fluorescent bulbs, the neighbourhood becomes pitch black. The city originally planned the street without lights, figuring a vibrant retail mix would light up the neighbourhood. “What we’re showing the world right now, because this is still considered the foremost intersection in the community, is an embarrassment,” says Sniderman.

It was this stretch that Bob Sniderman and Aaron Barberian, owner of Barberian’s Steak House on Elm Street near Yonge, stood at around 10:30 p.m. on a summer night 1993. The two, both second generation Yonge street business owners who knew street in its heyday, surveyed the sidewalks. The theatres had just emptied Cars whizzed by, but there was no sign of anyone — no tourists, no Torontonians, nobody. “We realized that it was almost contingent upon us as two of the only viable businesses operating at the evening to try and take the initiatives,” says Sniderman.

“Both Aaron and I had been involved because we had been sort of the heart and soul of the street.”

In the summer of 1996, 60 salt-shaker shaped “lady bug” trash cans were released onto the streets. They became a sensation, says Baerian, with their red and black exteriors emblazoned with YSBRA”s initials on the bottom — they were a cool attempt to bring life back to the street while keeping it clean. This initiative figured into the association’s initial strategy — clean up the streets. “We were dealing with very basic grassroots issues, get the garbage off the street,” says Sniderman.

The YSBRA is not an anonymous no-name group. Its members range from Sniderman’s Senator restaurant, to the Eaton Centre to Ryerson. In July 1995, the association incorporated, christened with the blessing of small business owners like Sniderman, with a consortium of businesses including the Delta Chelsea Inn, Toronto-Dominion Bank, and Cadillac Fairview. Though each sides’ bottom line showed drastic disparities, the two groups consolidated with one vision: Revitalize the core of downtown Toronto.

“It was like a sleeping giant,” says the Eaton Centre’s Kelly, who became chair of YSBRA in 1997. “All it needed was something to awake it.”

But Sniderman and Barberian, the association’s current chair, felt that their small steps — cleaning up, improving the streets — were not reserving the core’s decay. Yonge Street had hit bottom and it was time to make bigger strides. Cleaning up the streets did not bring high-quality retailers back. More businesses were moving out of the neighbourhood and replaced by stores operating on month-to-month leases. The intersection, the association felt, needed more than a face lift — it needed radical surgery. The problem was getting businesses and the city at the same table.

Project Chronology

- 1993 – Arron Barberian and Bob Sniderman meet up and notice the downturn of the street. They decide to do something about it.

- March, 1995 – The YSBRA and the city join forces.

- July, 1995 – The two restaurant owners, along with businesses like the Eaton Centre, incorporate the YSBRA.

- Winter of 95-96 – The city and YSBRA members hold meetings at the Top of the Senator at the Delta Chelsea Inn.

- Jan. 22, 1996 – Council adopts Downtown Yonge Street Comunity Improvement Plan. “The Planning Act gives the City special authority to acquire land, make loans or grants and enter into agreements with the private sector to undertake various community improvement initiatives.”

- March 11, 1996 – First meeting of the Yonge Street Regeneration Steering committee.

- April, 1996 – YSBRA hires Ron Soskolne to work on the Yonge Street Regeneration Project.

- June 24, 1996 – Soskolne says there needs to be a full commitment by the city to an aggressive redevelopment plan. A sub-group is formed. From now until Dec. 10, 1996, the group operated in secret to conceive the project.

- Sept. 1996 to July 1997 – Soskolne and Grayson negotiate about the fate of Ryerson’s parking garage.

- Nov. 28, 1996 – Soskolne writes the city planner, mentioning a deal with AMC.

- Dec. 2. 1996 – PenEquity receives an offer to lease from AMC.

- Dec. 10, 1996 – The project is announced for the first tim. The city in February announces that all the land is open to developers, but that parcel A, the site of the cinema, may be taken.

- May 6, 1997 – City council accepts AMC and PenEquity as the cinema tenant and the developer. A short list is developed, including Sniderman, for the other parcels of lands.

- May 7, 1997 – Sniderman declares a conflict of interest, stating that he is a participant in parcel C, the Salvation Army lands.

- Sept. 17, 1997 – Agreement between the City and Ryerson announced.

- Winter 97-98 – The Ontario Municipal Board hearings examines case.

- June, 1998 – OMB recommends project. City then passes final approvals.

- Summer, 1998 – OCAP pickets the Senator about the Salvation Army lands.

- Nov. 1998 – Property owners’ motion to appeal was turned down. The project will go ahead.

- Jan 15, 1999 – City will take possession of 12 parcels of lands for the project.

- Fall, 2000 – “Metropolis”, the cinema will be completed.

The Senator restaurant and the Top of the Senator jazz club were additions to the original diner, built a decade ago. The top floor jazz club attracts musical talent, and some well-placed patrons.

The cappuccino machine grumbles in the background as a waiter circles the customers, waiting to top off their coffee mugs. More than a dozen booth pack this restaurant, which has the kind of snug seating area with high-walled partitions that allow for just enough privacy. Eating at the Senator conjures images in 1950s movies where felt-hat toting power brokers held clandestine meetings to work out deals.

Which isn’t far from the truth.

It’s 1995. Ryerson’s new president Claude Lajeunesse and former Toronto Mayor David Crombie are dining at the Senator. Sniderman spots Crombie, Ryerson’s Chancellor and head of Toronto’s Olympic bid.

“This was one of the benefits I had was access to all these people who came to my restaurant, and I remember taking David Crombie aside and saying ‘David, we’ve got this association we’re working on for two years, we’re sort of spinning our wheels. How can we try to really attract more business to this area? Can you help us?” Sniderman remembers.

Crombie was later asked to chair breakfast meetings at both the Delta Chelsea Inn and the Senator, which drew bankers, businesses, city planners and politicians. At one particular meeting, the banks, who had long deserted the intersection in the past decade, were arguing that it wasn’t worth coming back. “David Crombie stood up,” says Sniderman, “and said ‘we’re not talking about Dupont Street guys. This is Yonge Street.”

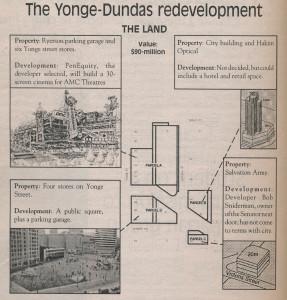

The development that stands to transform the edge of this campus is an offshoot of an arrangement of city planners, politicians and private developers. Any reference to the Yonge Street Regeneration Program will also mention that it is a joint public-private venture. In short, the $90 million development is the result of a perfect partnership. The developers have the capital, the vision and the marketing muscle; the city has the power to pass laws that are crucial to land assembly. It’s an unlikely union sparked by the YSBRA.

It’s a chilly autumn evening in October, 1995, and Mayor Barbara Hall is walking alongside Sniderman as rain sprinkles the Yonge Street corridor. Sniderman and Barberian are taking a few city councilors on a tour of the neighbourhood. The party starts at Queen, and walks north, and Sniderman points out the messy storefronts, panhandlers and littered sidewalks. The group retires to the Senator for a drink, where the councillors agree they must take a stake in the street.

City Hall was already sending a message that it wouldn’t tolerate Yonge Street’s decay. Earlier that year, at the same time YSBRA incorporated, the city adopted the Yonge Street Improvement Plan, which opened the door for improvements to the “public environment.” After that walkabout, the city passed a Community Improvement Plan which, in one fell swoop, took an area from Richmond Street to College. The lands to be expropriated and redeveloped are in the heart of this area. By defining an area in need, the city, through the Planning Act, can expropriate lands for redevelopment.

The YSBRA and the city formally joined forces in March, 1996. The public-private project, which was also funded by the two parties, was dubbed the Yonge Street Regeneration Program. David Crombie, by then, had given the YSBRA one more gift — a contract from his old days as mayor. It was in the form of Ron Soskolne, a chief city planner in the ‘70s, turned development executive in the ‘80s turned consultant.

“We hired Ron Soskolne as our project manager and we said, cure this neighbourhood of its ills,” says Barberian. “It’s a blank slate, come up with something.”

Soskolne headed the Regeneration Program’s steering committee and, later, oversaw a sub-group composed of YSBRA and city representatives that transformed a vision into a concrete plan: a public square, an urban entertainment centre and more retail. (The plan, the vision and how it was executed is explained in part two of our series, which is published in this issue). By Dec. 10, 1996, only nine months after joining up, the public-private team announced their plans for a radical downtown redevelopment.

The association and its members say without their push, the development would not have taken off. “There would be no possibility of it happening without the association. It would have just continued to be run down and it would be in worse condition than it was,” says Sniderman.

Although the project, barring an appeal by expropriated land owners, is out of the YSBRA’s hands, the association still holds some sway. “We’re the ones who are giving vision because the city doesn’t’ know what we need,” says Barberian. “We are the conduit for all the input on the development.”

Indeed, having small landowners involved in YSBRA gave the project some clout. “We focused the association down at the street level as opposed to up in the towers and in the financial core,” says Baberian. “We are the conduit for all the input on the development.”

Indeed, having small landowners involved in YSBRA gave the project some clout. “We focused the association down at the street level as opposed to up in the towers and in the financial core,” says Barberian. After he left the country for 12 years, he came back to the street where he worked as the manager of Sniderman’s Senator. When the city, Ryerson and the developers penned the redevelopment deal, they chose the comfy Senator to announce it. A place of irrefutable reputation and honesty. “If it was the TD Bank coming to Ryerson … do you think you guys would be out for them?” asks Barberian. “No. It’s the little places that you recognize. It’s the Senator — a great cup of coffee. You know hen Bob says it’s good, you know it’s good.”

Unfortunately for Sniderman, being tied with the development diverted the plan’s critics directly at him.

It’s a warm summer day in June, 1998. A couple dozen protesters stand arm-in-arm in front of the Senator, blocking access to the restaurant. Next door, the Salvation Army building is quiet, its Out of the Cold program shut down. Sue Collis, an organizer with the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP), stands outside with a megaphone. OCAP set up noon-hour pickets throughout the summer, and held larger protests in front of the diner, hurting its business. During one lunch h our, Collis says, the blockade prevented 20 customers from getting into the restaurant.

The issue for OCAP was the Salvation Army building next door, at 259 Victoria St. — one of the lands the city is scheduled to expropriate — and one of the programs that it runs. OCAP believes the development is driving the homeless out of the core, and that it was a concerted effort of the city and businesses.

“The owner of the Senator has been the head of the Yonge Street Business and Reisdents Association,” said Collis in August. “And this association is one of the major driving forces in the whole Yonge-Dundas redevelopment project. The Senator next door somehow missed that expropriation so they are going to get to stay.”

When asked recently about the protests, Sniderman said they had nothing to do with the project. He said the pickets were set up to pressure the city to reopen the Out of the Cold program.

Sniderman eventually submitted a letter to the city, obtained by The Eyeopener, saying that he had a good relationship with the Salvation Army and asked that the city proceed with reopening the program. OCAP used this letter to gain support from other business owners.

But by getting Sniderman to support the Salvation Army program, OCAP had unknowingly put Sniderman into an interesting situation about this land. That’s because he attained the right to develop the Salvation Army property — as part of the redevelopment — after the city expropriates it, winning that right during a two-step public process in 1997.

“I submitted an application for the redevelopment of that site and we have not come to terms with the city or have come up with formal plans,” says Sniderman. The city and Salvation Army say they have not come to an agreement on the status of the land.

Although Sniderman did not play an active role in the planning stages of the project, he sat on the Yonge Street Regeneration Project steering committee — a body formed by city and YSBRA representatives that formed the nexus for the redevelopment — from its beginnings in March 11, 1996 to October, 1997. He was also Chair of YSBRA for part of 1997.

Sniderman was also subject to criticism during the Ontario Municipal Board hearings, as land owners launched an appeal of the project. In its June 1998 support for the redevelopment project, the OMB said the following about Sniderman:

“One aspect of the process that is somewhat troubling and worthy of mention, given the undertaking by counsel for the City during the argument, is the role of Bob Sniderman. He was an active member of the YSBRA who initiated the regeneration project and became a member of the steering committee and privy to matters related under the confidentiality agreement. Once the project started to crystalize, which included the property adjacent to the Senator Restaurant which is owned by Mr. Sniderman, he resigned from his position on the Steering Committeee.” The report went on to say that, “The Board is satisfied that the [two-step public] process is fully transparent and open to competition by everyone interested in developing the site.”

The Board also said: “Many of the property owners found the use of a confidentiality agreement distasteful, given the fact that the City is a public body and no members of the YSBRA had their properties expropriated.”

During the period Sniderman sat on the steering committee, the project was conceived and passed by city council, although Sniderman did not sit on the sub-group that brokered the project which met in secret for a nine-month period. He declared a conflict of interest in May 7 1997, a day after the city approved the project and he subsequently resigned in October after the city approved his Request for Proposals, meaning that he had been accepted as the developer and was to submit a plan for the Salvation army site.

But he had earlier failed to declare his conflict of interest when the city announced that the Salvation Army land would be up for development. Rather, Sniderman had declared his conflict after he had passed the first stage of the process, when the city was calling for qualified developers.

Sniderman says the allegations made against him at the hearings were malicious. “There were claims that were made [at the OMB hearings] that were completely unfounded and bordered on slander that the work that I had done in forming the organization had been selfish or mercenary and I had an ulterior motive in trying to perhaps acquire this property.”

“The OMB listened for six months of testimony and listened to hundreds of evidence and witnesses and in the final analysis the OMB said expropriation is in the best interests of the community,” says Sniderman. “I feel vindicated by the decision of the OMB.”

There is also evidence to suggest that YSBRA members had the ear of PenEquity, the developer that will build the cinemas over Ryerson’s parking garage.

In a copy of the June 4, 1997 Yonge Street Regeneration Programme steering committee minutes obtained by The Eyeopener, Ron Soskolne, the program director, told the committee he needs an approved list of retailers from YSBRA to submit to PenEquity. The minutes say the “ultimate decision for retailing mix rests with PenEquity but they should be held accountable to guarantee the shared vision.”

Sniderman, present at the meeting, said he would “discuss the list with Directors at the Board meeting and submit to Ron ASAP,” according to the minutes. A YSBRA director asked who would be in control of retailing. Soskolne responded that, according to the minutes, “meetings continue with Penequity (sic); Glenn Miller [of PenEquity] will be at Board meeting.

“In the Final analysis we need Confidence in the ability of Penequity to ‘Make our dreams come true [The quote was attributed to Glenn Miller].’”

YSBRA’s role is interesting because they were partners in the regeneration program, but they also employ Soskolne, who pulled together the deal and has the respect of virtually all the players. Soskolne, at a recent interview, confirmed the contents of the minutes but said that YSBRA would merely suggest retailers other than themselves that they would like to locate within the development.

The sidewalk leading up to Barberian’s Steak House is littered with leaves in the mid-morning . The restaurant’s storefront, though, is cleared of the debris as an employee has just hosed off the area. Barbarian, the current YSBRA chair, waits outside as his picture is taken, and looks a the line of teenagers who have lined up around the block waiting for Black Sabbath to appear at the Sunrise Records store around the corner — a tradition on Yonge Street. “Maybe you should take a picture of them,” he jokes, pointing to a few youths. Yonge Street’s boosters hope that Torontonians and tourists will soon join these kids on a new street.

Barberian is excited at the prospects. “We’re seeing renovations up and north of Yonge and Dundas and south,” he says, “we see new retailers coming on board. Foot Locker, Urban Outfitters. You can just see the change and you can feel the change. People realize that this is an important neighbourhood.”

Leave a Reply