By Kevin Ritchie

It’s the kind of advice your mom might give if she’s tangle with Seattle riot cops wielding tear gas and rubber bullets. It’s the stuff that pamphlets are made of. Practical, yet evocative titbits like: “Maybe [pack] your favourite book if you’re stuck in jail for a long time” and “Wear diapers because you won’t have time to pee.”

The advice comes courtesy of Alan Keane, a trainer with activist group Co-Motion Collective, and Chloe Sage, a veteran protester from Vancouver Island. The two are teaching weekend courses in direct action. The workshop is hosted by transACTION, a group of Toronto-based activists and billed as direct action, legal and medical training for the April 20 protest against the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) in Quebec City.

Among 350 people registered for the workshop is Alex Lisman, chair of RyeACTION, RyeSAC’s activist wing and seven other Ryerson students. He is sitting in the Church of the Holy Trinity behind the Eaton Centre to find out what to wear, how to protect himself and how to make his presence felt.

Between 10,000 and 20,000 protesters, including a busload of 47 Ryerson students, are expected to demonstrate at the Summit of the Americas. Activists say the FTAA will give corporations more power, weaken democracy and harm the environment.

“I feel a responsibility to all the people on the bus,” Lisma says. “This, for me, is real training as an organizer and someone who’s responsible for people.”

Quebec City will be Lisman’s second major protest. He was among 25,000 protesters in Washington D.C. last April who opposed the IMF and World Bank policies. He hung back in an officially sanctioned march, but in Quebec there is a possibility he may wind up behind bars, he says.

Erin George, chair of the Canadian Federation of Students-Ontario (CFS-O) is attending the legal and direct action workshops so she can help other CFS activists from Newfoundland, Manitoba, Ontario and Prince Edward Island prepare for the protest.

George is concerned the new trade laws will put students at financial risk.

“Tuition fee regulation is considered a predatory pricing practice and therefore a barrier to trade,” George says. “This (the FTAA) means a complete deregulation of tuition fees across the country.”

CFS is also participating in the Second People’s Summit of the America’s—an educational forum taking place during the week leading up to the Quebec demonstration on April 21.

Despite the chaotic images of activists clashing with police on television—like at the World Trade Organization protest in Seattle—these protesters march in structured affinity groups of five to 20 people. In the first workshop, the participants “affinitize” and practice consensus decision-making.

“We’re not advocating aiding and abetting anything” says Bryce, one of the direct action workshop leaders. “This is just information. Spreading ideas and information is what democracy is all about.”

Bryce says the goal is to maintain street presence, and on the street there are different degrees of risk.

Protesters worried about getting arrested will occupy a green zone, which is usually an officially sanctioned march. A yellow zone is a little more risky. It involved non-violent tactics like blocking intersections. A red zone is typically characterized by the rubber bullets whizzing through clouds of tear gas.

To avoid serious bodily harm, a protester must keep up on the latest in activist fashions.

Sage struts through the church wearing a gas mask, a large red knapsack full of supplies and cardboard padding to protect her from rubber bullets. She and activist Alan Keane lead a discussion on how to dress and field questions like: “Can you discuss the pros and cons of helmets?”

Her gas mask costs $50 and has two filters: one for pepper spray and one for tear gas. Contact lenses are a no-no because they can be irritated by tear gas. Makeup, sunscreen and perfume can also trap gas. Sage carried a scarf soaked in lemon juice and vinegar in a Ziplock bag in case her mask is ripped off. She also packs a big bottle of water, oranges, power bars and quarters for phone calls.

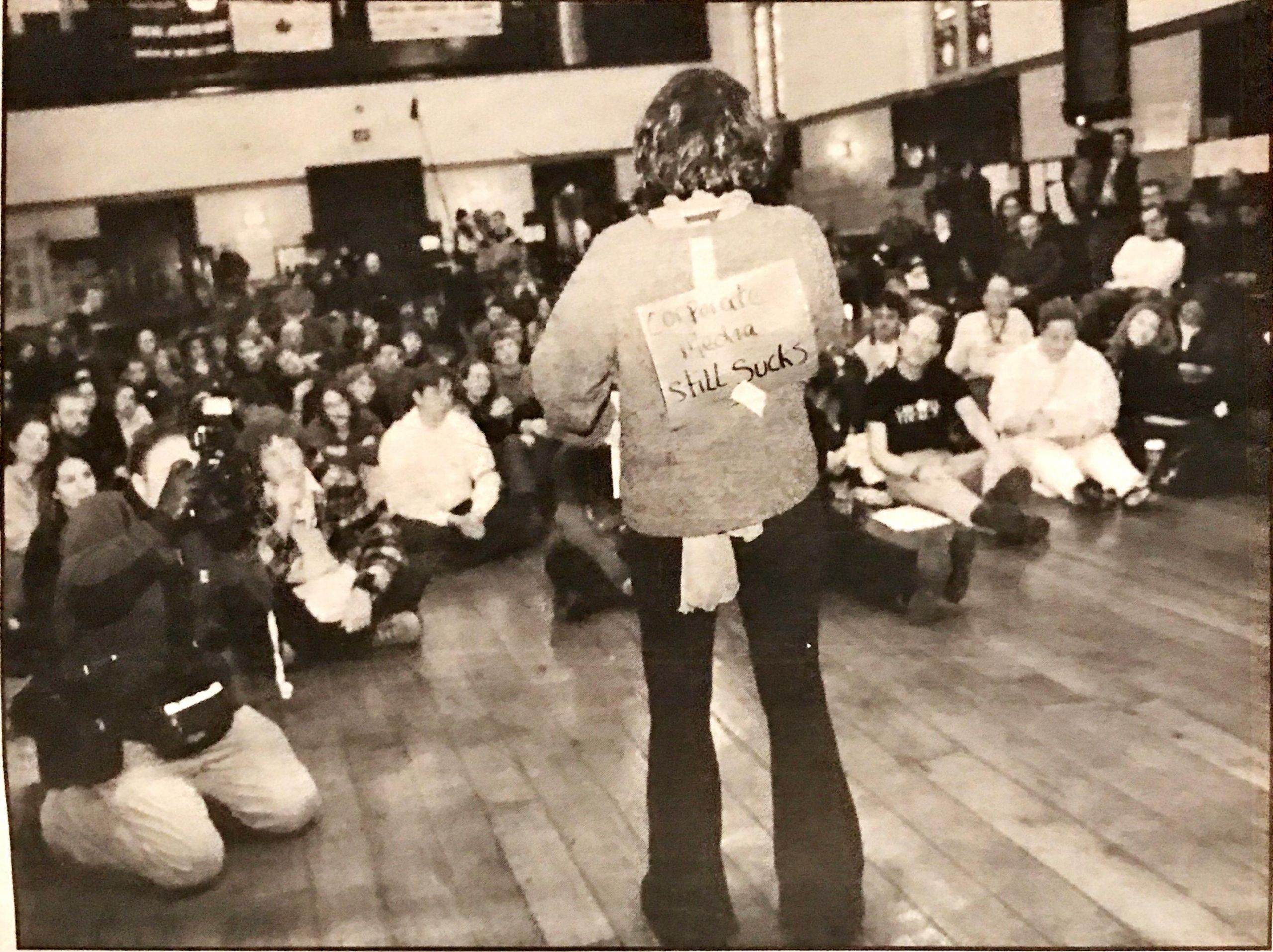

The mainstream media are invited in to watch the group brainstorm protest tactics. Bryce and Sage seize the opportunity and tape “Corporate media sucks,” and “Corporate media still sucks,” signs to their shirts.

Boom mikes hover inches from third-year social work student Krystal Ann Krause’s head as she writes down a list of 42 ideas on a large sheet of paper.

Krause stands up to present the list of possible protest tactics to the room. Among the suggestions: taunting the police by throwing tennis balls at them and asking them to fetch, abandoning cars in intersections and “de-paving,”—a suggestion from former Toronto mayoral candidate Tooker Gomberg. (He defines it as “liberating the earth and maybe planting something.”)

Krause’s bright red hair, “Resist of Serve” T-shirt, yellow whistle clipped to her waist and wild ad-libbing keep the crowd’s attention. She’ll make great eye candy for the 11 o’clock news.

Afterwards, Sage shows a video of more dangerous forms of protest. At a two-day demonstration test. At a two-day demonstration at a logging site in British Columbia’s Slocan Valley, Sage and two other protesters sit in hollowed-out wooden beams covered in barbed wire in the middle of a road. Their arms are attached by pipes covered in tar, chicken wire and duct tape. Rescue workers must cut through the pipes or somehow remove all three at once.

Sometimes demonstrators will wrap the pipes with kerosene-soaked cloths so rescuers can’t use power tools to cut them free.

Another video depicts a “sleeping dragon” tactic. A car is attached to the ground and a hole is cut in the bottom. The man inside is hard to see but seems calm as rescue workers try to get him out. His arm is in the hole and locked into the ground. The only way to get him out is by cutting off its arm, Sage says.

“Civil disobedience depends on whether the police care whether you live or die,” Sage warns. “I’m not saying you should. I’m just saying that you could.”

Leave a Reply