By Nicole Cohen

Traffic is heavy on the first floor of East Kerr Hall as students rush to Friday afternoon classes. No one looks up from conversations of coffee cups to glance at the painting on the wall.

It’s a painting that has adorned the wall between the doors of room QE127, across from the main entrance of East Kerr Hall, for 41 years.

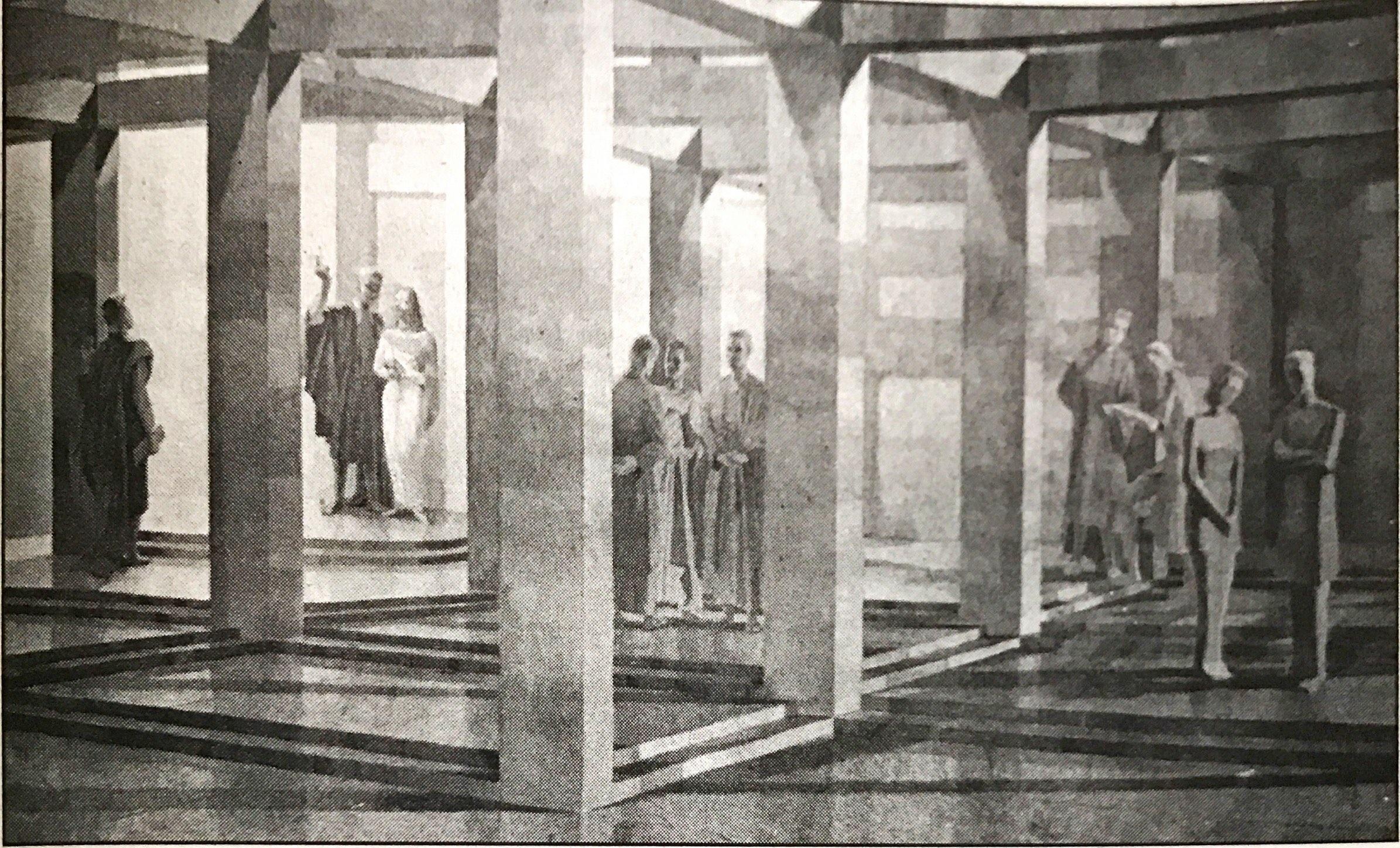

Painted by Allan Collier, The Portico of Philosophers portrays 10 male and three female students—quite differently.

Its soft pastel colours don’t hide the blatant fact that men are characterized as

academics and women as passive observers.

Not only are the men dressed in robes—more modest than one woman’s off-the-shoulder dress and another’s revealing skirt—but they are painted in a more intellectual light than women. The women assume flirtatious and submissive poses while the men are holding books and engaging in serious discussion.

Ann Whiteside, Ryerson’s discrimination and harassment prevention officer, scratches her chin and stares thoughtfully at the wall.

Whiteside thinks people could interpret the women in the portrait as being submissive and less intelligent than the men, but says when the painting went up in 1960, it was reflective of the number of female students at Ryerson.

As far as Whiteside knows, there hasn’t been anyone advocating for a change in the artwork. And she hesitates to say whether administration would consider its removal.

“You can’t change the past, but [you can] use examples of the past to make Ryerson a more equal and accepting campus,” she says.

It’s 2001, and the world has seen the rise of two women’s movements advocating a wide range of issues, from being treated as equals and getting the right to vote to legalizing abortions and gaining control over our bodies.

But while female students prepare to enter the workforce,a painting on the wall of their school subtly calls into question the climate in which they study—a climate they assume regards them as equals to their male peers.

Clearly feminists still have a lot of work to do. But the First and Second Waves—feminist movements from the mid-1800s to the late 1970s—are over, which leaves matters in the hands of a new generation of young adults, the Third Wave.

Many young women have rejected the seemingly radical label “feminist” and just call themselves girls, which is why The Third ave has been criticised by older feminists for being apathetic.

Third Wavers are looked down upon for choosing empowerment over political activism. They are seen as being too busy holding female music festivals and making cut-and-paste zines to lobby the government.

Politics professor Janet Lum warns against this “girls just want to be girls” attitude.

“They want to be equal but don’t want to be political,” says Lum. “Which is dangerous for the women’s movement.”

At the beginning of her women, power and politics class, Lum asks how many students call themselves feminists. She’s lucky is six people out of 100 raise their hands.

“I ask to see if [students] have stereotypes about feminism,” she says, “if they’ve adopted the negative connotations of feminists being radical, strident and anti-male.”

Lum tries to cast feminism in a more positive light and urges young women to continue to advocate for women’s issues.

“Young women today assume everything is hunky-dory,” Lum says.

Even though female students at Ryerson have equality in their programs, things may be different once they enter the workforce.

This fall, Statistics Canada reported full-time working women only make 72.5 cents for every dollar men earn and are still working in traditionally female dominated fields—health and social services, retail, education and food and beverage industries.

“If women don’t continue to be vigilant we will start to see some backtrack,” says Lum. “In the past [women] didn’t sit around. They analyzed and fought—the only way women made any gains.”

Lisa Weaver subscribes to the Third Wave notion that writing about women’s issues is just as important as being political.

“Some people think you’re not a feminist unless you’re holding signs and being very active,” she says. “But you have to do whatever you’re good at.”

The 25-year-old splits her time between her final year of Ryerson’s journalism program and co-editing McClung’s Ryerson’s women’s magazine.

She’s proud to say she’s a feminist, but is attracted to the movement because it’s accessible—young women don’t have to be militant and radical to wear the label.

Third Wave magazines such as Bust (a feminist-friendly version of Cosmo), and Bitch (a cheeky response to pop culture) are trying to erase the stigma surrounding the F-word by embracing women’s equality, diversity and sexual freedom.

But these are the exact traits The Portico of Philosophers undermines. And the paint isn’t going to peel itself off the wall.

“Everybody could be doing a little more than they’re already doing,” says Melissa Potter, 23, host and coordinator of CKLN’s Radio Active Feminism.

She says female students have to take a stand on campus issues.

She wants to see a more women positive mural placed beside the Portico of of Philosophers.

“The first step is to define yourself as a feminist and recognize that women are

still not equal,” she says. The next, she says, is to do something about it.

Potter and the Radio Active Feminism collective, a group of 10 women, raise awareness about women’s issues on the airwaves every Sunday 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m.

The things on Potter’s feminist agenda: eradicating women’s poverty and violence against women as well as eliminating the economic and racial divide that has cast feminism as a typically white, middle-class movement.

Potter, who graduated from business marketing at Ryerson two years ago, thinks students are so concerned with student issues they forget to take a stand on female-specific issues.

“My feeling about Ryerson is that it’s generally apathetic,” she says.

Ryerson’s Women’s Centre tries to strike a balance between being politically active and functioning as a resource and referral centre for students. “It’s a different level of activism than in the past,” says Komal Bhandari, Women’s Centre coordinator and fourth-year social work student. “We campaign and rally, but we also educate.”

The centre participates in Take Back the Night every years and runs letter writing campaigns about on-campus issues. In October, the centre sent a busload of people to Ottawa for the World March of Women. They are holding an International Women’s Day fair on Friday in the Olive Baker Lounge and participating in the International Women’s Day march starting at the University of Toronto’s Convocation Hall on Saturday.

Like many young feminists, Bhandari is concerned with being independent and having equal rights. But as she stares at Collier’s Portico of Philosopher’s, arms crossed and brow furrowed, it sinks in that Ryerson may still emit a subtle stench of sexism.

Bhandari isn’t surprised there haven’t been any complaints about the painting. “It’s important to look and question it, but as to when [change will happen], I don’t know.”

Leave a Reply