By Sutton Eaves and Jonathan Spicer

The bleet of an old brass trumpet danced with the soft thump of a wood hand drum. Protesters marched rhythmically to the music, the slap of their rubber-soled shoes on asphalt emphasized the baseline of the march. Flags snapped in the breeze, quickening the tempo the urban orchestra, and the low buzz of a kazoo exposed its grassroots underbelly.

Sounds of shakers swelled from the current of protesters. Hundreds of heads back while hand drums beckoned the march from ahead. The sounds of the march ran up the walls of apartment buildings, where people on balconies waved and danced to the cheers from below.

It was the sound of the street slowly approaching downtown Ottawa where a common enemy was gathered in the Government Conference Centre. It was there that finance ministers from the major industrialized and developing countries of the world were meeting with World Bank and International Monetary Fund officials to discuss ways to combat global terrorism and enhance economic development.

But it was the detachment of the meeting, the fortified agenda within, even the gagging of dissent that drew the crowds from across North America to Ottawa’s frosty streets. These were people without representation, marching to reclaim their voice in a democracy; thousands of people, young and old, protesting silence.

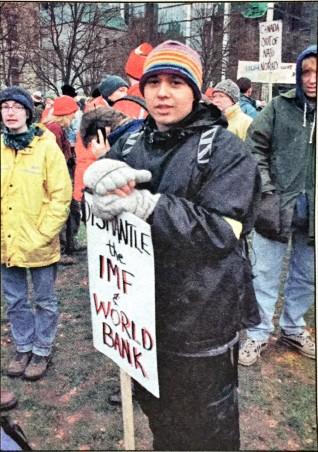

Underneath the banners calling for social reform, Carlos Flores, a first-year urban and regional planning student at Ryerson, walked in time with the drumming on a nearby bucket.

“There is a common element and that’s what we’re all fighting for,” he says. “It doesn’t matter what ideological perspective you look at it from, we all share the same goal and desire.”

Flores has come from further than most to protest the two-day G-20 meetings. Born in El Salvador, he moved with his family to Mexico at the age of one, before relocating to Canada when he was nine-years-old. Flores says it dawned on him then that his homeland was a country of refugees, torn apart by forces that weren’t native to El Salvador.

“Now that I’m older, I can recognise that they come from a lot of those values that Americans continue to instill. They use our land for resources — coffee plantations, sugar plantations — they specialize and break it down so that our country cannot produce more than one thing,” he says, still referring to El Salvador as “his” country.

“I’m still attached to the people — to their suffering,” Flores says.

Carlos Flores, a Ryerson planning student, was born in El Salvador and says h’s against the injustices committed in his homeland. Photo: Sutton Eaves

Protests like this are one of the only exercise in democracy left amd a central reason for his participation is that people must maintain a dissenting voice, he says. His home-made sign read: “Dismantle the IMF and World Bank.”

Over on the sidewalk, bobbing above other home made signs, is 10-year-old Kristina Hick. She is perched atop her father’s shoulders, who strides along in the swirling protest.

“I saw what the IMF did around the world with their Structural Adjustment Programs. I saw what they did to the people that they were supposed to help — but didn’t,” says Steve Hick, a professor of social work at Carleton University. He lived in Southeast Asia for two years and the SAPs that he refers to are a hot spot of controversy in the realm of international loans.

“In the Philippines, for example, (the IMF) got them involved in high-yield rice varieties rather than their traditional rice varieties. So they were switching all over, but the high-yield varieties needed all of these pesticides and fertilizers that you could only buy from developed countries. It got… peasants hooked into the high-yield, highcost production with more problems than they had before,” Hick says.

Kristina says she was there to protest against child labour, but was startled by the heavy police presence.

“It’s a little scary. All the police were there with all this armour on and all these dogs barking at you,” she says.

Full-grown protestors shared Kristina’s fear of the packs of German shepherds as many of them experienced first-hand the wrath of the snarling reinforcements.

10-year-old Kristina Hick came with her father, a Carleton social work professor to speak out against child labour. Photo: Sutton Eaves

“The police dogs were vicious, and provoked the crowd if anything,” said Melanie, a street medic who asked that her last name not be used. “The police tried to intimidate us with [the dogs], and it worked.”

Melanie, a third-year Ryerson photography student, said she was specially trained to treat the protesters. She first got involved as a protest medic during the Summit of the Americas in Quebec City last spring.

A survey of the crowd, which reached the doorstep of the G-20 meeting, revealed new faces of resistance: many sporting swimming goggles, medicals masks and hockey helmets.

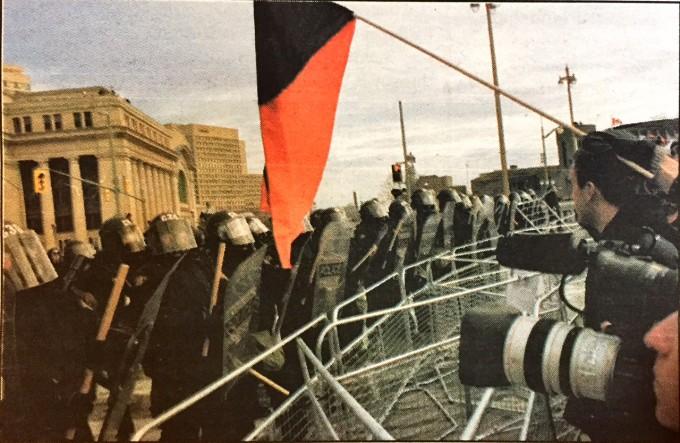

As they pushed aside a heavily guarded steel barricade, parts of it were tossed into the Rideau Canal. Now, protestors and riot police were separated only by a thin stretch of waist-high fencing. Bandana-covered faces reflected in the dozens of plastic riot shields only a few feet away.

The capital city’s war memorial — a battalion of Canadian soldiers charging forward with a cannon — loomed above.

Walking swiftly through the crowd with a fellow medic, Melanie listened for the cries for help. Someone shouted “Medic! Medic!”, and she turned quickly on the rubber sole of her heavy combat boots, already reaching into the deep pocket of her cargo pants for the non-latex gloves she carried with her all day.

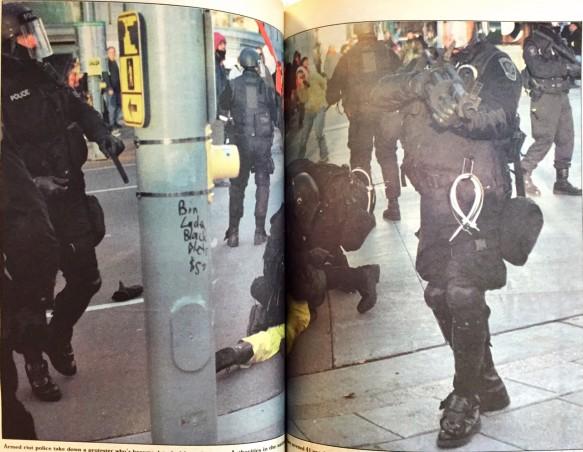

A protestor, caught in the frenzy of fence-shaking and bottle-throwing, had been blasted by police with a white powder. Its only distinguishing characteristic was the burning sensation in left in his eyes and throat and on his skin. The colour of his dark jacket was hidden beneath the layer of fine, white chemical. Melanie doused his eyes with a soothing solution she pulled from her first-aid fanny pack to calm the searing blindness in his eyes. With rubbing alcohol, she decontaminated his skin.

Protestors all around nurse their own injuries — rubber bullet wounds and blasts from water cannons being the most common. Monstrous lime-green hydro tanks rolled in behind the line of riot police, ready for action if the protestors got too rowdy.

Despite the tension, there was little violence between the contending groups. Although 41 protestors were arrested, mostly disturbing the peace, many were released the next day.

“Ottawa was a peaceful as we could keep it… in Quebec City, as soon as we approached the fence we were attacked. Here, protesters were able to maintain composure in that moment of tension,” said Flores. “If you look at it from a peaceful perspective, it was successful.”

And up the street, beyond the bonfire and above the war zone, there was action of a different kind. Coin-filled pop cans, hand drums, and a cow bell drowned out the shouts below. Some people sat and swayed, other tapped their feet. A small circle was dancing a sort of tribal samba.

“I know the world is possible; I know the world is possible.”

The drumming and dancing circle, now about 30 people strong, moved without warning and as a single body down towards the standoff. A woman swinging a silk sheet, a man dancing in snow pants. Their rhythm spreading quickly through the group.

“Talking about revolution; talking about revolution.”

Leave a Reply