By Amy O’Brian

My undergraduate degree has been revoked.

I’ve been informed via e-mail.

I stare at the happy, multicoloured Yahoo screen in total disbelief, going over the words with bug-eyes and a frantic hope that it’s some sort of cruel joke. But it’s from Trevor Barnes, my third-year human geography professor at the University of British Columbia, and is written in formal, academic prose.

“Dear Miss. O’Brian,” the e-mail reads. “I was going over the essays you wrote for my urban geography class and it came to my attention that most of what you wrote was quite obviously plagiarized. Unfortunately, I have had to inform the Dean of Arts, who has chosen to revoke your degree.”

I rack my brain for anyone who could have access to the information in the e-mail: the name of the professor, the course he taught. But I haven’t spoken with anyone from that class in years. I’m sure it’s legitimate and that I must have inadvertently plagiarized an essay I wrote over three years ago.

I convince myself that despite my crippling neuroticism about citing sources, I have done something horribly wrong that has resurfaced to plague and destroy me.

Once the shaking subsides and I’ve read over the e-mail enough times to have it memorized word for word, I hit Reply and send a panicky memo of denial and disbelief. I then slide over to a corner of the room where a large folder containing everything I ever wrote in university sits covered in dust.

By this point, the situation has produced some tears, but I squint through them to find two essays I wrote for Barnes in 1998. One is a geographical interpretation of Joy Kogawa’s memoir Obasan and the other is a piece about my perceptions of Vancouver’s downside eastside. Both are riddled with elementary opinions that could not possibly have been lifted from any published source.

Then, I remember. A friend in the course got a two-month extension on the downtown eastside assignment and asked to use my marked essay as a guideline for his own piece. Months later, I found his version of the assignment and noticed that he’d lifted two of my paragraphs verbatim. We exchange a few violent words, but eventually forgot about it and moved on. And now I’m screwed.

After re-reading the essays, I call friends and family to get their advice. I interrupt one friend in the middle of a dinner party, she sympathizes and believes the e-mail could be legitimate. Another friend tries to convince me it’s a prank, pointing out that no self-respecting professor would have a Hotmail account. But I can’t figure out who would do such a cruel thing or have the information and the means to send the e-mail. My sister is convinced of its authenticity and warns me that a long battle with UBC lies ahead.

So, I’m not the only one who fell for it. I’m not the only one who considers an e-mail “From:” tag equivalent to a signature — something that inherently indicates the authenticity of the sender. I’m not exactly computer savvy, but I trust e-mail and had no idea that, with the proper software, it’s possible to type in any address and mask the identity of the sender.

Apparently it’s not hard to do, and if you have a dark sense of humour, you could have heaps of fun sending out fake e-mails signed by whoever you like — the kind of fun that causes other people stress headaches, crippling self-doubt and the appearance of a gullible buffoon.

I eventually traced the source of my own two hours of hell back to Vancouver. After a few expensive phone calls, I tracked down the evildoer who answered laughing and said, “Did you get my e-mail?” He thought it was hilarious and had used the trick as a lure for me to call.

The “prank mail” software was developed by his computer-programming roommate for an assignment at the prestigious British Columbia Institute of Technology. His professor did not admonish him for ignoring legal and ethical boundaries, but instead congratulated him for his ingenuity and awarded him a top grade.

E-mail impersonation is considered a variation of fraud under Canadian law, an offence publishable by fine or imprisonment. And so it should be. It’s a federal offence to tamper with someone’s snail mail or tap their phone without authorization, so why is e-mail security not taken more seriously? Just think of the damage you could do with the power to impersonate anyone you wanted in an e-mail.

The West Coast culprit sent similar prank mails to co-workers and other friends.

One message was sent to an ambitious friend doing his MBA at the University of Toronto. The prankster composed an e-mail from a Microsoft headhunter claiming to have met the recipient at a networking dinner, and asked if they could meet to discuss future employment. Fortunately, this guy is far smarter than me (that’s why he’s doing his MBA), and didn’t take the bait.

The prank mailer demon also sent notes to his colleagues at a halfway house for teenage Vancouver runaways. Former B.C. Premier Gordon Campbell informed readers they were fired due to cutbacks in social programs. The e-mail could have sparked a violent outburst or caused a worker to not show up for work, and be fired for real.

The repercussions and the consequences of these prank mails could potentially ruin, or at least dramatically alter someone’s life.

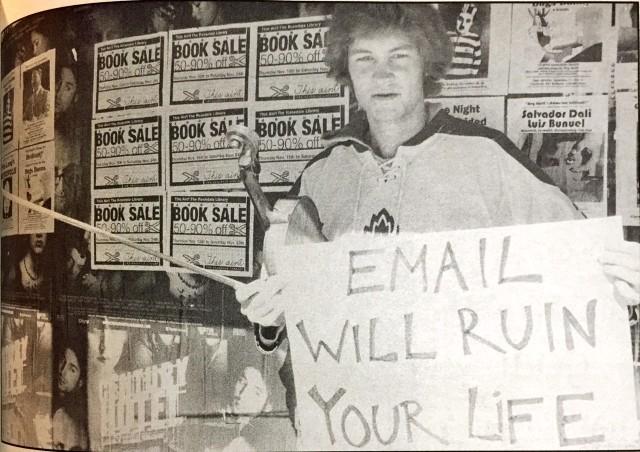

Be grateful that you’ve learned this lesson: e-mail is not to be trusted. Rapidly advancing technology, coupled with the difficulty of regulating Internet communication, has made e-mail a powerful tool of manipulation and deceit. So if ClaudeLajeunesse@hotmail.com sends you an e-mail saying you’ll be graduating earyl because of your displays of sheer genius, please don’t stop going to class.

Black e-mail

E-mail screw-ups can be more than just embarrassing, cyber messages have torn apart friendships, marriages and offices. Some examples of the destructive power of e-mail:

Fast forward: Peter Cheung, an investment broker working in Korea, sent an e-mail to eleven friends at Merrill Lynch in New York boasting his sexual conquests and extravagant lifestyle. “The main bedroom is for my queen-sized bed, where CHEUNG is going to fuck every hot chick in Korea over the next two years,” he wrote. His friends hit “forward” and the email was soon read by thousands of people, including his boss. Three days after sending the message, he was asked/ forced to resign. Reported by Shift Magazine, July 2001.

Email Gate: Archived White House e-mail messages were subpoenaed throughout various Clinton/ Gore scandals, including the impeachment proceedings. White House employees claim they were threatened with jail if they disclosed the existence of “lost” e-mails, which included Al Gore’s private e-mail account. The White House eventually turned over some of the subpoenaed messages, exposing various gaffes, lies and indiscretions. Reported in The Washington Post, Sept. 2000.

Law and Disorder: Two Ontario Provincial Police officers who e-mailed crime-scene photographs to colleagues were charged with discreditable conduct. The e-mails contained shots of an injured aboriginal male and the autopsy of a white female. The Natural Resources Ministry fired six employees and reprimanded 100 others after a similar incident. Reported in The Global and Mail, August 2001.

Leave a Reply