By Kevin Ritchie

First impressions aren’t important. If you are walking through a park and you spot a well-dressed blue-suited Bay Street-type stranded 16 feet above in a giant American beech tree might give him the opportunity to explain himself.

Others aren’t so lucky.

Like the prostitute at the corner of Church and Carlton Streets. Or the 14 year old who stole your wallet.

“To know someone as an individual, you have to wipe away all your assumptions,” says William Phillips, a Ryerson film and director of Treed Murray, a Canadian movie that opens in Toronto on Dec. 7. “It’s very easy to say what a bunch of punks. People fall into a trap where they stop noticing what’s going on around them.”

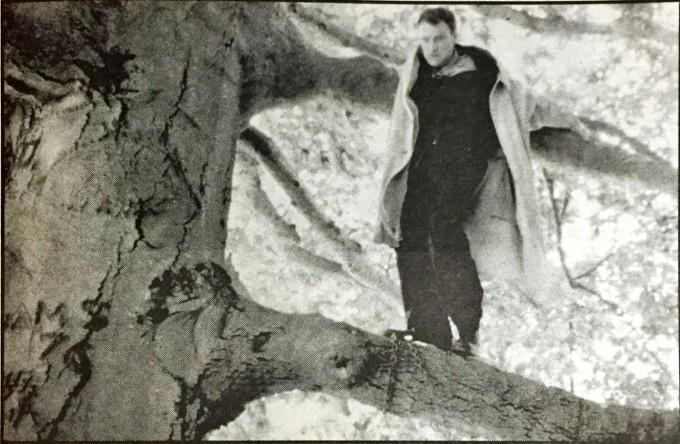

In Treed Murray, an advertising executive named Murray (David Hewlett) is walking through a large park when a 14 year old tires to steal his wallet. Frustrated, Murray decks the kid with his brief case and is chased through the park by the kid and his friends. He climbs a tree in desperation and when they find him, they wait him out, demanding an apology.

As Murray tries to manipulate his way out of the situation, Phillips plays on the assumptions we make about people. In the beginning, he purposely filmed the gang in long shots, so we don’t get to know them right away and they seem more menacing. As the movie progresses, the camera moves in for individual close-ups of the gang members. The camera work forces the audience to take a second look at the kids and suddenly Murray doesn’t seem like the victim.

“I would hope it’s an entertaining story first. I think it’s important to put that in the forefront,” Phillips says. “I don’t expect it’s going to change the world. If it makes someone think — that’s cool.”

Treed Murray is successful because it keeps up the suspense without pandering to it’s audience and forcing its message down their throats.

In an effort to save money, Phillips set the story entirely in one location. “Just so you know, putting a guy in a tree isn’t expensive. It’s a complicated thing.”

Hewlett spent most days during the shoot on a tree branch 16 feet off the ground, which meant a stunt co-ordinator had to be on set every day. While beautiful, the tree was less than co-operative. The American Beech tree (located in the Boyd Conservation Park in northwest Toronto) changed colour eight times. When it rained, the algae in the bark turned green.

There were also problems with noisy birds and beechnuts raining down on the actors during scenes. The crew had to re-construct the tree in a studio to film the close ups.

All the movie magic and pratfalls aside, the film received a warm reception at the Toronto International Film Festival in September. It was Phillips’ first time attending the festival to support a movie. He has submitted two short films in the past and still has a rejection letter written by former festival programmer Helen du Toit.

Du Toit produced Treed Murray.

Phillips graduated with a science degree from the University of Toronto in 1986 and went on to study film at Ryerson. He graduated in 1991 with two short films under his belt — Snake, the story of an executive with a mental disorder that made him act like a snake and Blink, an artsy flick told through a series of tableaus.

“You have to make a few shorts to get recognized,” he says. “One thing leads to the next. You do need luck, but it’s not impossible.” Phillips got funding for Treed Murray after he made a short film called Deep Cut that explored similar styles and themes.

He’s currently working on a script called Foolproof for Alliance Atlantis and anticipating Treed Murray’s opening — the same day as the star-studded Ocean’s 11.

Let’s hope audiences don’t make assumptions about either film based on the size of their marketing team. Phillips says there’s a variety of Canadian films out there. Treed Murray follows Canadian films like Cube and Ginger Snaps that are fun and smart with slick production values.

“I like to wind things up,” Phillips says. “Some films get thinner and thinner. I think people should walk away with more.”

Leave a Reply