By Natalie Alcoba

Inside an unassuming school building, on a sleepy Regent Park street, thrums the heartbeat of a community filled with anticipation.

Drummers, dressed in a potpourri of colours, pound on cowskin African djun djuns. The beat pulses through the gym of the 153-year-old Park Public School, matching the frequency of feet tapping, hands clapping and hearts pounding.

Hundreds of eyes are fixed on the back door. Heads bob, trying to lay claim to the perfect vantage point in a sea of onlookers. Hands flail, sashes wave and fists thrust in the air. In the last row, a little boy is carried up and down the aisle on dancing feet. Despite repeated attempts, his mother cannot contain his energy. And then, as the anticipation nears its breaking point, a light-skinned, grey-haired man appears.

Madiba, Lion of Africa. Nelson Mandela.

He beams, smiling that unforgettable smile and greets the crowd as if it were family. Despite his 83 years and failing health — he recently underwent prostate cancer surgery — he is light on his feet and starts dancing, keeping in step with the African beat. The people cheer.

He and his wife, children’s advocate Graca Machel, were in Toronto this weekend to raise money for the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund. They attended several events Saturday morning, including the renaming ceremony of Park Public School and the presentation of honorary degrees to the couple at Ryerson. On Monday, Mandela received an honorary citizenship at the House of Commons.

“You are the future leaders of the world and it is an honour for us to be here to interact with you,” said Mandela, addressing over four hundred school children who now attend Nelson Mandela Park Public School.

“There are children in other countries who are very poor who want help and are pleased to know that the children of this school have identified themselves with the children of South Africa.” The school has raised money for the fund.

Born Rolihlahla Dalibhunga Mandela, he grew up as a member of the Thembu royal family. He was given the English name Nelson by an African teacher. As a child, Mandela attended a local mission school and in 1938 enrolled at Fort Hare University College. He sat on the student council, but was suspended from school after protesting white colonial rule. He moved to Johannesburg and eventually earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Southern Africa in 1941.

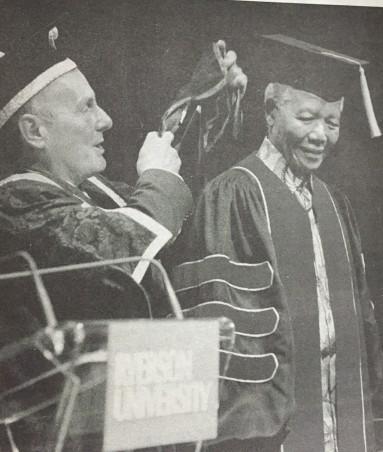

Dressed in Ryerson’s grey and red graduation gown, Mandela was presented with another degree, a doctorate of laws, on Saturday morning. He told the more than 1,100 people seated in Ryerson Theatre of how proud he and his wife were “to be admitted to the Ryerson honorary alumni of this university.”

“We come from a country quite recently emerged from an era and a political regime in which all of its major social institutions were put to serve sectional minority interests and not those of broader society,” he said. “[Ryerson’s] focus on technological education of quality sets an example that we can follow.”

Mandela grew up in apartheid-era South Africa. As a young man, he joined the African National Congress, a political group, and fought to change the political system that segregated and oppressed blacks. In 1960, the ANC was outlawed and Mandela was imprisoned shortly afterward.

During the 27 years he spent at Robben Island prison, he negotiated with the government to bring democracy to the republic of South Africa. He was released in 1990, and in 1993, a democratic political system was instated. Mandela was elected president of South Africa in 1994.

Machel has dedicated her life to educating the people of her home country, Mozambique. She urged the crowd, which included students, faculty, and politicians, to “break down the linkages between poverty, discrimination and violence.” She was Mozambique’s minister of education from 1975 to 1989 and chaired the United Nations Study on the Impact of Armed Conflict on Children.

“In these amazing times, 600 million children in the world live in absolute poverty, on less than $1 a day,” said Machel after receiving her doctorate of laws.

“Using their strengths as academic institutions, universities, such as Ryerson — which is now my university — can change the nature of the discourse on implementing child rights and child protection internationally,” she said.

Mendela spoke of the importance of compromise to affect change. “When you are regarded as a threat by others, no matter how talented you may be, you will make no impact,” he said.

“The most difficult thing in life is to change yourself. You cannot influence and change others if you yourself are not prepared to change.”

Leave a Reply