By Sutton Eaves

Ramzee Jon Blackstone leans back casually in his chair, occasionally running a hand over the silky black pony tail that runs halfway down his back. He twists his seat rhythmically from side to side, gripping the arms so that the soft, scarred skin on the inside of his forearms is visible. The puckers of flesh are circular and pink.

“They’re cigarette burns. Me and my friends like to burn ourselves, cut ourselves too sometimes,” says the 25-year-old Anishinabe Indian, thrusting forward hands etched by switchblades and grinning in a what-the-fuck-do-you-think-of-that kind of way.

Again, another grin, and a chuckle as well.

“Can I light you on fire?”

From a dim office in the basement of the Native Child and Family services centre, Blackstone laughs about being an alcoholic and addicted to drugs, boasting of his four-day clean streak, but quickly admits that he doesn’t intend on staying that way. He spends much of his time in the drop-in style teen centre at Yonge and College Streets.

He wears a faded black T-shirt with the face of Che Guevara silk-screened on the front, the ink cracking from multiple washes and wears. He graduated from high school when he was 17 on his own whim, moving from city to city and enrolling himself in classes wherever he went. He confesses his love for reading, and he hopes of becoming an actor and writer, like “Hunter S. Thompson — beatnik kind of stuff.”

He talks at length about colonial oppression, land rights, residential schools. He talks about racism and hate, of which he has both been the target and the instigator.

For all of his views and opinions on the oppression of his culture, Blackstone seems to miss the vital piece that holds him in place as the stereotype of native youth. All the time he spends resenting and fighting against the assimilation of natives into the culture of white Canada is wasted on what he could be doing — finding and revelling in the pride of his culture and looking to its teachings for solutions to his despair. That’s how Waubegeshig Rice sees it. He sees this paradox of identities and trying to fend off the stereotypes around being native that are at the root of the problems native youth face today.

“Knowing and having pride in the tradition of our cultures really helps you figure out who you are,” says Rice. “It’s something you can hold on to when things are hard. It may even be the only thing you have at certain times.”

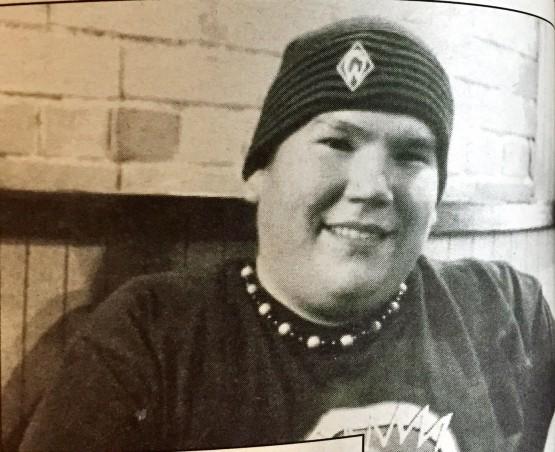

A fourth-year broadcast journalism student at Ryerson, Rice, who likes to be called by his nickname Waub, works as the Circle Facilitator for the Ryerson’s Aboriginal Student Services centre, organizing social and cultural events for the 100 or so native students on campus. They are events that help foster a sense of belonging that is missing for aboriginal youth.

“The biggest issue is lack of identity — trying to figure out exactly who you are and what your place is in Canadian society,” he says. “Every native youth that grows up on the reserve faces it — it’s the Catch 22 of our culture. When you grow up on a reserve you have traditional ways and your people and the reserve all around you. But at the same time you have a TV in your house, you have a radio, and you are being constantly bombarded by another culture. Another culture that looks way better than yours. That’s why a lot of people who grow up on reserves, who grow up in dismal conditions end up being depressed and abusive… and the cycle of abuse just keeps going on and on.”

An Ojibwa Indian, Rice, 24, grew up on a reserve near Parry Sound, Ont. He looks like a pop-cult product in a chunky beaded necklace and multi-pocketed khaki cargo pants and he fits in perfectly with the other students guzzling draught beer and greasy wings in the basement of Oakham House. But his almond-shaped, coffee-bean-brown-coloured eyes expose the difference between him and the rest of the students in the pub.

But the way Rice dresses is not at all an indicator of any attempts to hide his native identity, nor does it have anything to do with the way he sees his culture. He has a deep belief in the healing value aboriginal tradition holds for so many troubled native youth.

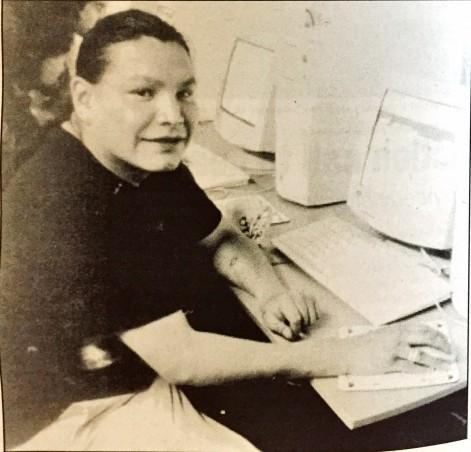

Ramzee Jon Blackstone surfs the web in the Native Child and Family Services Centre. Photo: Sutton Eaves

Ryan McMahon, a youth co-ordinator at the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto, maintains ties to his Ojibwa roots through dance, song and theatre. The 24-year-old university graduate has worked with youth at the centre for over a year and has seen first-hand the issues that trouble Toronto’s native youth.

He encourages the kids he works with to explore their heritage and be proud of their tradition. He is hopeful too, that this generation and their successors will experience a fundamental pivot in mentality, allowing them to break the cycle.

“There’s a teaching given to us by our elders that talked the seventh generation — the seventh generation after contact, that is, and colonization. We are the ones that are supposed to start the change and draw a new path and a new circle.”

McMahon says it’s not just about teaching native youth to be book-smart. He says formal schooling is not always the answer for everyone.

“Traditionally, we didn’t have books and paper. Our teachings were oral — singing and dancing, which told ancient sacred stories of our history. A lot of art and our paintings, our theatre, mask making, they all tell our stories. We can’t abandon that. Instead, we must embrace it and use as a vehicle for learning and growth.”

Rice agrees, adding to that by saying part of the educational proves must include more relevant curriculum for native youth. He stresses the importance of integrating native culture and cultural practices into education in both native and integrated schools.

“It provides the sense of community that native people really value and need. Integrating culture into education — we’ve grown up with the teachings of the Canadian school system, which doesn’t focus on the positive aspects of native history. If you can integrate these cultural ways and traditional practices into education than it makes education more relevant for us, and gives us something to take pride in.”

Maxine Poulin, a first-year general arts student at Ryerson, went to an integrated high school in Sioux Lookout, which suited her well as a child of culturally diverse parents. Her mother is native, her father isn’t.

The polar opposite of youth like Blackstone who identify their upbringing on reserves as the root of their problem, Poulin says that because she did not grow up on a reserve, she’s not as familiar with her culture as others, which is something she regrets. It’s also something she plans to rectify by learning more about native culture.

A sense of pride in your history is vital, says Poulin, but so is having positive native role models. Both of her sisters completed university and each got jobs at Air Canada as flight attendants, becoming success stories of Sioux Lookout. Having them to look up to encouraged Poulin to work hard and get to university.

“It depends what options the kids have for themselves, and if they have anyone motivating them like I did. Really what they need is role models,” she says.

McMahon and Rice are both hopeful that aboriginal teens are beginning to recognize the importance of practicing and taking pride in their cultural heritage, instead of futilely trying to battle against the cultural assimilation that youth like Blackstone directly feed into. In turn, they can find a unique identity and break free of the stereotypes that hover over them still.

Back in the little office in the basement of the Native Learning Centre, a young native who is disguised and defined by a heavy chemical cloak to most who meet him, shares his philosophy on life.

According to the prose of Ramzee Jon Blackstone: “The way I see it, we’re all just spirits, floating around in this sacred nightmare.”

Leave a Reply