After five moves and five disappointments, third-year social work student Judith Craig hopes she’s finally found a place to call home.

By Lora Markova

For the first time in three years, Judith Craig smiles at the indulgent thought of a hot, soapy bubble bath.

In her cozy new apartment she says she has a big bedroom, spacious living room, full kitchen and bathroom and ample storage space.

“It’s delicious. Truly delicious,” she says of her new abode, which she moved into in December.

“My landlord has been wonderful so far. Things that need to be repaired, she’s repaired them already. She’s upgrading things for added safety and precaution, which speaks really loudly to me. She’s gone out of her way, so I really felt comfortable moving in there.

It may sounds as if Craig is easily impressed, but considering what she’s had to put up with over the past three years, it’s understandable that she feels that it’s heavenly to come home.

After living in mouse and cockroach-infested hovels, sleeping in converted bathrooms with holes in the floor and risking break-ins in sketchy neighbourhoods, she has more than paid her dues.

Since moving out of her parents’ Mississauga home in 1999, Craig’s rented five different apartments in the city — each seemingly worse than the one before.

And Toronto’s tight, ever-shrinking rental housing market makes I a safe bet that for every horror story like Craig’s, there are many more that go unheard.

Ore than 100,000 new people move to Toronto every year, but there are only six available apartments for every 1,000 occupied. It’s statistically impossible for everyone to land the apartment of their dreams first time around.

“When I get together with people and we talk about moving,” Craig says, “I always seem to be the one who has the worst horror stories to tell. But I definitely think the problem is widespread. And I think there are a lot of bad landlords who try and take advantage of students because they think we’re young and stupid.”

Craig’s quest for the perfect apartment began in August of 1999, as she entered her first year of Ryerson’s social work program. She and her roommate, Judith Cornwall, signed a one-year lease for a two-bedroom apartment on Howard Street, just south of Bloor Street, in Cabbagetown.

Craig wasn’t worried, though, until she met “the Alberts.”

“Some say it is sick to name your mice that invade your house, but we got so used to seeing them scurry across the living room and eat through boxes in the kitchen they became like a family,” Craig says. “No matter how many times we would catch and kill an Albert, a family member was never far behind.”

When the two women approached their landlord about the problem, they were told every building in Toronto has mice and not much could be done about it. After many attempts to reason with him, they took the task upon themselves.

“We were given some cheap and cruel flat sticky traps which trapped the mouse,” Craig said. “Then you had to flip them over to kill it — not pleasant at all.”

Soon Craig discovered that the Alberts were not their only pests. Little brown cockroaches were also living in the apartment and seemed like they were there to stay. The roaches were more disturbing than the mice, and more difficult to catch. They had dashed across the floor and hid in cracks and holes.

Despite please to their landloard for help, the problems went unsolved.

The same happened after their first attempted break-in: nothing. The perpetrators had almost broken off the door handle, which the landlord agreed to fix, but he wouldn’t fix an additional lock, which had been installed by previous tenants.

“It’s all about saving that extra buck,” Craig says.

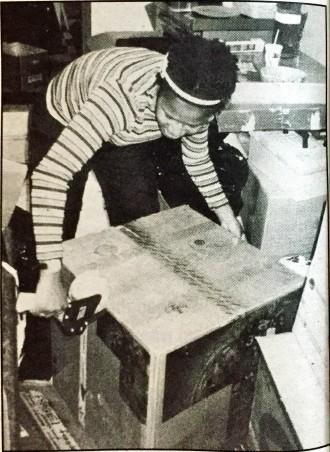

Craig couldn’t pack her belongings up fast enough when she was finally able to move out of the apartment. Photo: Lora Markova

Although students are not the only ones suffering from the housing deficit, they are one of the primary targets for bad landlords, says Marco D’Angelo, director of educational affairs for the student union at Carleton University in Ottawa.

“Landlords love students,” D’Angelo recently wrote in an article published in the Ottawa Citizen.

“Landlords violate lease agreements, charge exorbitant deposits and do not make necessary service calls for repairs, like fixing the furnace in the winter, because ‘it’s just a bunch of kids.’”

The two women moved out of the Howard Street apartment one year later, after the landlord deposited their rent cheque into someone else’s account and accused them of skipping out on the monthly fee. By then, Craig had been looking for another apartment for over six “nail-bitting” months. She was able to sign the lease on a new place before she had to leave the old one.

On September 1, 2000, Craig and a friend from her program moved into a small, two-bedroom, basement apartment on Kendal Avenue, near Dupont subway station. She thought she would be happy, but soon found out that the only good feature of the apartment was its location.

The new pad had no mice, as far as Craig could tell, but presented a variety of other problems. Monthly floods soaked their carpets and ruined their furniture. The gas stove was faulty and it almost burned her several times. The landlord had also promised them a washer and dryer set for the house but that never appeared.

“The best was when (the landlord) used us to sell the apartment to the next victims,” Craig recalled. “We were being honest and the people really appreciated it. Unfortunately, a couple who didn’t speak good English ended up taking that run-down, mouldy place.”

When the lease was up, Craig was out.

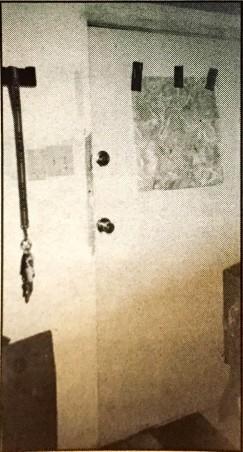

A large crack in the door let Craig and anyone else peer inside her pad, but she often had trouble getting in — a finicky door lock regularly refused to cooperate with her key. Photo: Lora Markova

In July 2001, she moved into a small bachelor apartment near Ossington Avenue and Dupont Street. The apartment was too small to hold all her belongings and she was paying $575 a month, but at least the landlady seemed nice, she thought.

She soon discovered, though, that ‘nice’ doesn’t mean ‘handy.’ Her landlady was lazy, Craig says, and didn’t care too much about the maintenance of the house.

“When I discovered that I had some flurry little friends, I told her, and she told me to buy poison,” Craig says. “When I told her that hadn’t worked (before), she wanted to know what I expected her to do about it.”

According to the Landlord and Tenant Act, landlords must make sure that the place they are renting out meets certain health standards, which include getting rid of pests.

If tenants are concerned about a landlord’s actions, they can bring their issues to a number of different organizations. The Toronto Rental Housing Office and the Ontario Rental Housing Tribunal both offer a place where tenants and landlords can file complaints. In addition, the Centre for Equality Rights in Accommodation promotes and works to protect the human rights of disadvantaged individuals and families.

Because Craig was well aware of her options and unwilling to fix everything that broke in the apartment by herself, she broke the lease after two months. But the worst was yet to come.

Last September, Craig moved into a one-bedroom basement apartment in the Dufferin Street and St. Clair Avenue West area. She took the place at the last minute and, as a result, was unable to examine it carefully. The people who had lived there before her were very dirty, she said. When she went to look at it, there were clothes and garbage all over the floor.

“The state I viewed the apartment in was disgusting,” she says, “but my landlord made promises that repair would be made by the time I moved in.”

There had once been wall-to-wall carpeting in the apartment, which had been ripped out at some point. Underneath there was dirt, mould, and dead bugs. The flooring now consisted of oddly shaped pieces of linoleum, that were duct-taped together.

“She handed me a roll of duct tape and some bug spray to ‘handle’ the situation,” Craig said. “I should have known then and run like hell, but I thought ‘I’m going to make it as homey as possible,’ and that’s what I set out to do.”

Craig painted the walls and hung pictures, but more and more problems jumped out at her every day. When her landlord finally agreed to take care of some of the repairs, the jobs weren’t completed.

In the bedroom, there was a gaping hole in the middle of the floor, which Craig covered with duct tape. It turned out that the room had originally been a bathroom and the hole was where the drain had been. This also explained why the floors were slanted towards the middle of the room and why there were pipes sticking out from the wall behind her desk.

Besides all these major problems, there were many minor, fixable problems that persisted. The roar of the fridge drowned out conversations. A large crack in the door allowed Craig to peer inside her house even though she often had trouble getting in — a finicky lock regularly refused to cooperate with her key. To top it off, the stove constantly burned Craig’s favourite treat, banana bread, because it had no knobs and didn’t show the temperature.

The landlady ignored all the problems and when Craig finally pushed for them to be fixed, the landlady “lost it” on her.

“She doesn’t know a good tenant when she has one and I refuse to be treated like a child,” she says. “(The landlady) said if I didn’t like it there, I could give her notice and leave and that is just what I (did).”

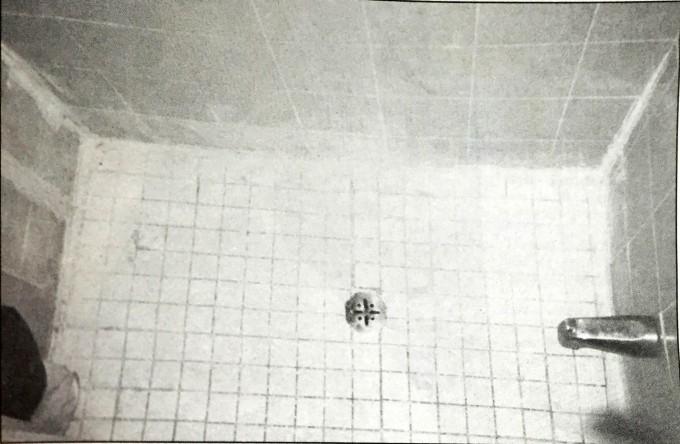

This nasty, cramped shower stall had actually been repaired only two months prior. The handyman stuck cocking over the existing tiles where grout and scum had been building up for much too long. Photo: Lora Markova

A student’s tips to find a happy home

- The initial contact is very important, says third-year social work student Judith Craig. “I’ve talked to people on the phone and I’ve been like, no, I’m not even going to bother because it’s a waste of time. I know that’s not what I want. You have to ask them enough questions initially to know whether it’s a place you even want to go and see.”

- This is also a chance to get a feel for the landlord. “You aren’t seeing them, so you have to read their voice, the intonation, their tone, their manner with you, the questions that they ask,” Craig said.

- Make a list of the things you want, need and can sacrifice, Craig suggests. Safety and comfort should be decisive factors. “Make a huge list. Even if you think you’re asking for too much, make it. The Ryerson Off-Campus Housing office has a list, which is an excellent place to start and grow on… Ask other people. I get asked a lot now and I can always think of things to add to the list, just from my own negative experience.”

- You should always bring someone along as a second pair of eyes. “Having other people’s opinions and taking somebody with you is important,” she says. “I’ve learnt to be extra observant. Observations skills are very important. You have to really be on your guard. You have to look out for you, and you have to be a little selfish, because nobody else is going to think about you.”

- “I look for everything included — utilities, laundry. I look for any signs of mice, or anything that’s falling apart or needs repair. I look for safety, comfort, no duct tape on the floor.”

Leave a Reply