By Rachelle Younglai

It’s just a lead, they say.

The khat leaf has sparked controversy and has caused Toronto’s Somalis to routinely break the law to chew what they say is a drug at the cultural essence of their community. Health Canada says the khat leaf, pronounced cat, is more harmful than tobacco. But Somalis say chewing khat has long been at the heart of their culture and locals say its ban has caused strife in the community and made them a target for harassment.

For centuries, Somalis have chewed the leafy growth. It was used as a stimulant to dispel feelings of hunger and fatigue, and is now mostly taken socially to promote communication and feelings of excitement.

But Somalis say it’s tradition.

“When there’s a Somali event you must bring khat or else it will be incomplete,” says Idrisosaman Mandar, the director of the Somalia family and child skill development agency. “If it’s missing everyone will go away.” Mandar says khat is common at social gatherings such as weddings and engagements.

Khat is to Somalis like beer or coffee is to North Americans, he says.

“You cannot get mad,” he says. “It’s not substance abuse, it’s not hallucinogenic. It makes you happier and the atmosphere better.”

Some would describe these feelings of euphoria as those related to the intake of amphetamines, synthetic drugs that stimulate or increase the action of the nervous system — and are sold as street drugs in uppers and speed.

And it is for those effects on the body that a Health Canada spokesperson says khat has been placed on the list of controlled substances. It is also banned in the United States and in some European countries.

But the community members in Toronto question how Health Canada could ban something without conducting its own research. “I believe they are relying on British studies,” says Faisal Hassan, a Somali community member. “And why after doing studies in the U.K. is khat still legal and taxed in Britain?”

In England, khat can be found in grocery stores next to the vegetables and herbs.

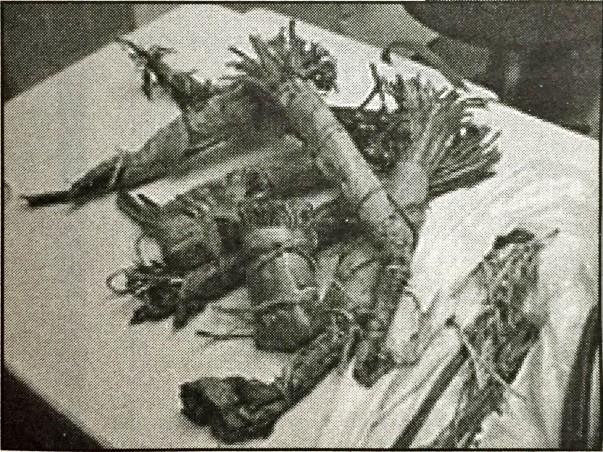

Khat, also called qat, chat or jat, is a large shrub which can grow to tree size. It originated in Ethiopia and spread into Kenya, Malawi, Uganda, Tanzania, Arabia, the Congo, Zimbabwe, Zambia and South Africa. The shrubs are grown interspersed between coffee trees. But khat has a short shelf life — between 35-40 hours — before it starts to rot, so it has to be cut, bundled and shipped out onto the street quickly. It looks similar to rhubarb and cannot be preserved. Taken from the khat shrub (Catha edulis), the two active ingredients in the leaf, Cathine and Cathedone, are prohibited under the Canada Drug and Safety Act. In 1997, Health Canada banned these ingredients after the World Health Organization made recommendations to the United Nations.

“They said the effects resembled those of amphetamines,” says Ryan Baker, spokesperson for Health Canada. And Heath Canada has a long list of khat’s toxic effects which includes insanity, hallucination, addictive properties, psychological problems, psychic dependency, increased blood pressure and cardiac problems.

Whatever its chemical properties, what lies at the centre of the controversy is that Heallth Canada placed a ban on khat without consulting the Somali community and without understanding what khat is.

“There’s a lot of bitterness in the way khat was banned,” says freelance journalist Ali Shariff. “Ever since it happened there are problems in the community.”

Community members say they feel like they are being unfairly targeted. During the past summer undercover police search Somali hang-outs, making arrests and angering the community. They also were upset when unmarked police cars would pull people over to search for khat.

Community members believe that police are using the search for khat as an excuse for harassment and are unfairly targeting their community.

“It’s a strong community,” says Hassan. “(Police) are attacking the community because they are not involved with crime or drugs.”

Hassan says the harassment may be a way of breaking up the community. “It’s a way of banning community activity.”

Staff Sergeant Robert Hnatshyn of Toronto police’s 12 division in the west end of the city disagrees with the notion that police are targeting the Somali community. “We’re pretty fair,” Hnatchyn says. “The last thing we want to do is start a civil war.” Hnatshyn doesn’t think there is a rampant problem with khat.

Shariff says there has been a lot of defiance in the community as people continue to use the illegal khat. That defiance breeds resentfulness against police and government.

Mandar wants to see the evidence that proves that khat is harmful and argues that the WHO and Health Canada do not have any scientific proof. Aside from his personal experiences with khat, Mandar says that he understands the Somali community sufficiently to know that khat is not as destructive as officials say it is. Mandar says his organization was the first group in Toronto who informally surveyed the community and tried to look into the effects of khat, by systematically asking people a series of questions — how often khat is used, how much is used per week, how much is spent on khat per week. He says his results show that khat is just a stimulus and that it’s not addictive. “It will not harm you. There’s no disadvantage, no aggression,” Mandar says.

Shariff agrees, saying violence does not come with khat.

But despite this, Health Canada remains adamant. “Our position is that it’s a controlled substance,” says the spokesperson Baker.

And khat within the community is not without its own problems. Mandar says that like alcohol and tobacco, it can sometimes lead to economic troubles if families spend more money on the leaf than on groceries.

But Baker disagrees with Mandar’s assertion that khat is like tobacco. Obviously there are risks associated with tobacco, says Baker, but they are relatively mild to what khat can do to you. “Khat poses a greater risk,” Baker says.

There is also controversy in the way the substance is controlled. Toronto airport authorities see most khat shipments stem from England. Grown in East and North Africa, and transported either by courier or in large cargo shipments of up to 60 kilos, its most common journey to Pearson airport is via Heathrow, London.

And although the spokesman for Pearson Airport’s drug enforcement squad, Corporal Larry Foy, acknowledges that khat is cultural and says, “we don’t want to frown upon a whole community. It’s still illegal. We still have to do our job.” From Jan. 1, 2001 until the end of September Pearson saw 169 seizures of khat valued at about $3,118,000. Sentences are light, which is an issue for police.

Detective Mike Booth of the Peel Regional police drug squad says “They don’t sentence like it’s a problem.” Although law enforcers agree that khat is not on the same level as harder drugs such as cocaine and heroine they say the police who make the arrests are not backed up by the legal system. Police are told khat is illegal but the light sentences don’t back up their claims or deter users.

And Foy agrees that the sentences do not deter couriers and buyers but says that khat is not nearly as big a problem as heroine or cocaine. A gram of khat costs about 50 cents and a gram of crack cocaine can cost $200. Khat couriers receive nominal amounts for their work, such as the cost of the airfare or a small amount of cash, and those caught for possession are released with a small sentence. Cocaine carriers can serve life sentences if they are caught.

In the end, Mandar says that everyone loses from the khat ban — the government loses the money it could be making from taxing khat and the community loses because it has limited access to the plant and people caught in what they see as a cultural misunderstanding.

Leave a Reply