By Don McHoull

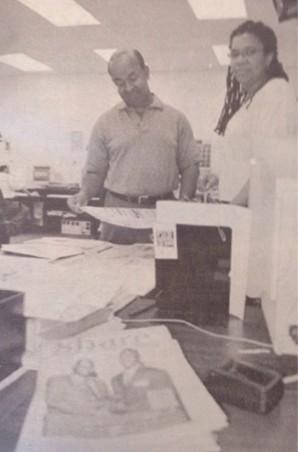

Arnold Auguste wants to tell the other half of the story. If mainstream newspapers focus only on the negative aspects of Toronto’s black community, Auguste is determined to provide a balance by focusing only on the positive. As founder, publisher, and executive editor of Share, the largest publication serving Toronto’s black community, Auguste is in a position to put that vision into practice.

“If I want to read about crime in the black community, I’d read the Toronto Sun,” Auguste says. “I’d much rather print a story about a young black man winning an award, than a young black man committing a crime.”

Members of the black community need to have their self-esteem lifted, Auguste says. Coming to a new country, they are bombarded by media coverage that exploits the negative elements of their community — violence, poverty and drugs. “I want them to see that they didn’t make a mistake in coming here,” Auguste says. “There’s a lot of good things going on in this community.”

Some people are questioning Auguste’s decision to cover only positive news. CityPulse reporter Jojo Chintoh has witnessed violence in Toronto’s black community up close while working as a crime reporter.

“I was covering black on black crime back in 1989, and I got a lot of flack from the community for it,” says Chintoh. “But this is something that we as a community can’t just ignore, that we have to deal with. Why isn’t Share covering it?”

Auguste says Share leaves reporting on crimes to the daily papers. “As a weekly, we’d also be behind them, printing old news. I prefer to address issues like that on the editorial page. We’ve taken very strong positions about how the community has to take responsibility for things like violence.”

He founded Share when he was just two years out of Ryerson’s journalism program and heavily in debt. Twenty four years later, it is the dominant newspaper for Toronto’s black community. Every Thursday, 50,000 copies are distributed to newsstands across the Toronto area. Share is expanding into the suburbs, where an increasing number of its readers live. Over the summer it began sending copies as far away as Windsor and Montreal.

While many other papers have gone out of business, Share has persevered and prospered. The paper reaches more than 150,000 black readers every week, and businesses targeting that demographic clamour to advertise on its pages. A typical 31-page issue is packed with ads for black hair care products, West Indian grocery stores and firms that ship goods to the Caribbean.

But it is the editorial content that Auguste believes truly sells his paper. After 30 years of working in Toronto’s black press, Auguste has developed very strong ideas about the type of newspaper he believes the black community needs. With Share, he has put those ideas into practice, giving his readers a wide range of international news, from Jamaican cricket scores to coverage of African politics. He also gives readers a broad mix of opinion columns, and has taken a strong stance on Canadian immigration and the war against Iraq in his editorials.

When a 23-year-old Auguste came to Canada from Trinidad in 1970, there was nothing like Share being published. The main paper in the black community was Contrast, which was aggressively political. “Contrast was a lot more strident, coming after the sixties, with black power and all that,” says Chintoh, a former editor of Contrast. “Share is much more moderate.”

Auguste wrote a column in Contrast in the early seventies, before coming to Ryerson. After graduating in 1976, he was hired as an editor at a black community newspaper called Spirit, where he worked for less than a year. He was fired because the paper couldn’t afford to keep him. He was then hired to edit Contrast, but soon came in conflict with the paper’s owners.

“Arnold didn’t really fit in at Contrast,” says Chintoh. “He wasn’t very political, and he wanted a more positive focus on the news, which they didn’t agree with.”

Within a year Auguste was fired again. Finding there was no newspaper in the black community that agreed with his views, he decided to start his own. “I didn’t originally set out to own a paper, I just wanted to write,” he says.

When Auguste launched Share, it was run out of his Eglington Avenue apartment and published 2,000 copies a week. After the third issue, someone firebombed his apartment, destroying all his possessions, but he kept on publishing.

Auguste designed Share to stand out from the other black community papers, folding the front page backwards and displaying a colour magazine style cover on the back. It was the first ethnic paper in the city to be given away free.

While the other black community papers hired almost exclusively from their own community, Auguste took a colour-blind approach. For him the most important thing was hiring reporters with journalistic training.

Lisa Lareau, who is white, is still surprised that Auguste hired her out of journalism school in 1980.

“I didn’t really know that much about the black community at the time,” she says. “I think mostly what he wanted was to see his community covered thoroughly, and it didn’t mater to him what colour the reporter was, so long as they could do that for him.”

Within a few years, Share was turning a profit and Contrast and Spirit were out of business.

Although it has struggles through some tough economic times, Share has never lost money, and today it is the leader of Toronto’s black community press. A handful of smaller papers such as Pride and Caribbean Camera attempt to compete, but are not considered serious rivals.

“I don’t even worry about the competition outside, because we don’t have anybody close to us. We’re competing with last week’s issue,” says Auguste.

For almost 20 years, Share was run mostly by editor Jules Elder. Auguste developed the paper’s positive vision, but it was Elder who implemented the founder’s ideas. Elder says that a positive approach to the news does not preclude covering crime. “That’s a misunderstanding,” he says. “We’d cover crime, it’s just a matter of how you’re covering it. It wouldn’t be sensational, we’d try to get to the root of the story.”

Over time Elder’s vision for the paper drifted too far from Auguste’s, and four years ago he departed to write for the Toronto Sun. Auguste took over as editor for the first time since the paper’s first few years in business.

“I really didn’t like the direction the publication was going in,” he says. “So when [Elder] left, it gave me a chance to get back involved and do what I want to do.”

Since Auguste took over as editor, the paper’s circulation has gone up by more than 50 per cent, and has increased from 20 to 32 pages.

But Elder says that while the paper has grown, it now focuses more on covering community events, and less on looking at the roots of problems in the community.

“They’re still doing much of what was done before, but maybe not to the same extent,” he says. “We had the people who were prepared to go out and do the digging.”

When Elder left, most of the reporters left as well. All writing is now done on a freelance basis, and Auguste has assembled his own team of writers.

Ryerson journalism professor John Miller has worked with Auguste and Share’s writers in workshops on developing story ideas. Miller said that not all of the writers were happy with the positive-only news policy.

Covering bad news might scare away some advertisers, says Miller, but ignoring it hurts the paper’s credibility. “If a newspaper is glossing over part of what’s going on, it’s going to lose the trust of its audience.”

Auguste argues that Miller doesn’t understand Share’s role in the community.

“John should understand the difference between the community newspaper and the mainstream newspaper,” Auguste says.

Share’s steadily growing circulation is proof that readers agree with his positive news philosophy, Auguste says.

“Success is the answer. We’re successful, and we keep growing, so that ought to tell you we’re on the right track.”

Leave a Reply